Joan Amondi, Jean-Hervé Bradol, Vanja Kovacic & Elisabeth Szumilin

Joan Amondi graduated in Literature (Moï University, Eldoret, Kenya). She has worked for MSF-Crash as an interpreter, a translator and a research assistant.

Medical doctor, specialized in tropical medicine, emergency medicine and epidemiology. In 1989 he went on mission with Médecins sans Frontières for the first time, and undertook long-term missions in Uganda, Somalia and Thailand. He returned to the Paris headquarters in 1994 as a programs director. Between 1996 and 1998, he served as the director of communications, and later as director of operations until May 2000 when he was elected president of the French section of Médecins sans Frontières. He was re-elected in May 2003 and in May 2006. From 2000 to 2008, he was a member of the International Council of MSF and a member of the Board of MSF USA. He is the co-editor of "Medical innovations in humanitarian situations" (MSF, 2009) and Humanitarian Aid, Genocide and Mass Killings: Médecins Sans Frontiéres, The Rwandan Experience, 1982–97 (Manchester University Press, 2017).

Vanja Kovačič

PART 3 Cultural stereotypes and the health seeking behaviour of HIV/AIDS patients in Homa Bay, Kenya

Vanja Kovaĉiĉ and Joan Amondi

I. INTRODUCTION

1.1. “AFRICAN SEXUALITY” AND THE SPREAD OF HIV

Homa Bay is located in the western part of Kenya, one of the areas in the country most severely affected by HIV. The estimated prevalence is 14% higher than the national prevalence (Chiao et al., 2009; MSF France, 2009; National AIDS Control Council, Kenya, 2005), which inevitably leads us to the question: Why this is this the case in Homa Bay and not in other parts of Kenya?

The reasons for this disproportionate distribution of HIV are frequently attributed to the cultural practices and traditions of the Luos, an ethnic group predominant in western Kenya. Luo culture, with polygamy, sexual cleansing rituals, and wife inheritance,Sexual cleansing rituals, regulated by strict rules, are still practiced particularly in rural areas of Nyanza province to celebrate planting and harvesting, childbirth, etc. Widows are expected to undergo such rituals after a period of mourning to honour the memory of a dead husband and free themselves to re-marry. Widow inheritance is often related to both rituals that last only a couple of days, to remarriage, which is a longer commitment to the new husband who, according to tradition, should belong to the family of the deceased.has created a fertile ground for culturalistic We use the term “culturalistic” to refer to the broad definition of “culture” as a set of shared attitudes, goals, beliefs, behaviours, practices, etc.discourses on the spread of HIV in Kenya among scientists, medical specialists and the Luos themselves.

Dating back to colonial times, these are certainly not new. Literature from the period abounds with explanations on the spread of specific diseases, particularly sexually-transmitted ones, and how this relates to the culture and behaviours of local African peoples. In the 19th century, for instance, there was a simultaneous outbreak in Uganda of non-sexually transmitted treponema pallidum pertenue (yaws) and sexually transmitted treponema pallidum (syphilis). Both infections were attributed in the medical texts to the “immoral behaviour” of Africans (Vaughan, 1991). Africans were not only seen as looking different and being susceptible to disease, but also as having different sexual inclinations and behaviours, which went on to become defined as “African sexuality” (Caldwell et al., 1989).

“African sexuality” was divided into two categories: male and female sexuality, and female sexuality, with the latter becoming the focus of some considerable colonial attention. The black African woman was described as degenerate, primitive, and passionate and was used as a synonym for the prostitute and the female animal. She was described as “doubly dangerous, being both African and wild, and female and wild”, (139:1999). She was an icon of sexually- transmitted disease, in contrast with the women of 19th century Britain who were seen as “reproducers of race” and whose female sexuality was “successfully tamed” (Vaughan, 1991).

During the initial stages of the HIV epidemic, such racial stereotypes were used to determine attitudes towards the spread of the disease. But as “race” went on to become a more sensitive issue in the scientific arena, arguments on specific cultural traits fuelling epidemics became a convenient substitute.

1.2. LUO CULTURE AND THE SPREAD OF HIV

In the case of the Luo ethnic group, the notion of a culturally-driven spread of HIV is deeply rooted and, surprisingly, even now has not moved on from the colonial perception. Culturalistic approaches appear not only in peer reviewed scientific papers (see for example Ayikukwei et al., 2008; Ogoye-Ndegwa, 2005), but they are also common among healthcare providers, including MSF (see End of Mission, Kenya (2003-2007) internal report).

There is doubtless an intuitive reasoning behind culturalistic arguments. Sexual cleansing rituals, wife inheritance, and polygamy are slowly dying out, but they still play an important role in everyday life in the rural areas of Luoland. However, who is best placed to talk about their culture? Here is what the Luo elders have to say about the spread of HIV:

“In the old days, younger people respected older people, but not anymore. And people never used to die like they die today. Men in the old days, they were between 23 and 25 (years old when they got married), but now even 15-year olds get married. Women used to get married at the age of 19 or 20. In the old days, younger women respected their parents, they waited (sexual activity) until the right time! They waited until they got married. And parents needed to approve the marriage. In fact, in the old days, girls got married as virgins, but not anymore. The girls, once they got married, they would stay there (at home), even if they were young. People would not go anywhere else (to have extramarital affairs), it was not the custom at all! But now it doesn't happen that way. Right now, girls go out to look for money from the men. They engage in sex for the sake of money, to help their parents. And in the old days there was no disease (AIDS). But there is a disease now and it is killing people, so people depend on other people to look after them... So people engage in sex for the sake of money. There are a lot of nightclubs, discos. And there are young men and they marry young girls without their parents’ consent. These younger men work as casual labourers. So they keep the money and at night they go to discos and they get diseases there. And again, when they go home it is the responsibility of the older people to look after them when they fall ill. So it is a problem... Wife inheritance in the old days, it was done for the sake of the children. Then women could not look after their children alone. Food, clothing, basically the man took care of them. But nowadays, even older women remarry younger men, which is disrespectful. In the old days, there was wife inheritance but (it was regulated), it had to be a brother-in-law, whose background was known about by the lady (widow). And the older people needed to sit down to discuss and they had to approve, before the inheritance took place. But nowadays, in modern times, it is not like this anymore... People go and marry just anyone. And it is even worse, because of this disease, this deadly disease (AIDS). Now people just marry at random” (Elder, Homa Bay, 19/4/2010).

The elders, who have witnessed their community struggle with HIV for decades, are stating very clearly that it is not ancient Luo culture, but a change in this culture - a shift in the way it is practiced or the practice of this culture with very different rationales - that is the reason for disease, death and an aggravation of health and social issues. An important point they make is that the culture, wife inheritance, for example, was regulated and governed by certain rules and that the elders were responsible for ensuring that the codes of conduct were heeded in accordance with the rationales on which they were based. The advent of a more western lifestyle with its discos and so on, a loss of respect for erstwhile social rules regarding marriage, the access to cash-paid labour and the HIV epidemic itself, exerted new existential pressures on the community and contributed to the spread of disease far more than the “old” Luo culture. According to the elders, had this “old” Luo culture remained untouched, it would have, on the contrary, fought to prevent HIV infection. Furthermore, so far, no sound epidemiological evidence has been offered to support the culturalistic approach on the spread of HIV or weigh it against other debates centred on economics or physiology.

1.3. WHO IS GUILTY AND WHO IS RESPONSIBLE?

It does not matter which – racial stereotypes, such as “African sexuality” or the cultural uniqueness of the Luos – both have been successfully used from the outset of HIV control in simplifying discourses on the spread of HIV until now. While it is taken for granted that polygamy and prostitution are responsible for the spread of HIV in Africa, nothing much is said about HIV infection caused by medical intervention. However, when Gisselquist et al. (2003) examined crude risk measures for HIV infection in Africa through to 1988, they provided evidence that exposure to healthcare caused more HIV than sexual transmission, promoted as the main means of transmitting the disease. Furthermore, the authors argue that this evidence was deliberately ignored in order to maintain public confidence in the healthcare sector. Thus, as often happens, culturalistic approaches are automatically defined to represent the culture of patients or communities but ignore the powerful, possibly even more dominant culture perpetuated by healthcare systems and their medical interventions. In fact, the latter are rarely called into question.

Thus, the will to maintain public confidence in healthcare often results in biased views. The example of health seeking behaviour we present in this paper discloses details of one such bias and further suggests that blaming the patient is commonly used to divert responsibility from healthcare providers who contribute substantially to the problem. It is important to keep this in mind, since attitudes to HIV epidemics have always been inseparable from individual, cultural, national, and international blame. Much caution is necessary because a culturalistic approach may be used not only to over-simplify the complexity of an issue, but also as a reason to justify inequitable distribution of healthcare in the future. Unfortunately, in times when sustainable ART funding is uncertain, this is not mere conjecture.

II. WHY DO PATIENTS DELAY IN ATTENDING FORMAL HEALTHCARE FACILITIES?

One issue stemming from the culturalistic approach became apparent to us during our research on health seeking behaviour Health seeking behaviour refers to different treatment options used by patients, with the focus on the reasons for their choice and the factors that contribute to associated decisions.among Luo patients. The question was: why do some patients take so long to access HIV-related treatment? The question originated from the observation of numerous patients in Homa Bay hospital wards who are bedridden and suffering from severe forms of opportunistic infections. During discussions with health workers we realized that the common assumption is that these patients prefer traditional treatment to formal western treatment since it is an intrinsic part of their culture. The other assumption was that they wait to be very ill before going to a formal medical institution. Hence, these common assumptions are based on the patients’ culturalistic beliefs and clearly imply that the solution lies in exploring and changing their attitude.

As will become apparent, the results of this research showed that culture did not play a major role in keeping patients away from medical facilities, or at least not the culture practised by the communities in question. But, the medical institutions and the culture they perpetuated did contribute to creating barriers to early treatment. This of course opens a fraction of the blame mentioned above and provides the opportunity to initiate a discussion on the sharing of responsibility between patient and healthcare provider.

Health seeking behaviour is often examined, as was our research, to steer patient behaviours towards institutionally desired actions. Healthcare providers promote HIV testing and early treatment of HIV-positive individuals because these have many advantages: easier administration of treatment, less side effects, and better prospects of recovery before the onset of medically-challenging opportunistic infections such as TB, meningitis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, etc. (Harries et al., 2004). In addition to the physical benefits, patients also profit from early treatment in social terms since the symptoms of the initial stages of the disease, such as skin disease and severe weight loss, show little or not at all which prevents them from being stigmatised. Moreover, they remain fit and are able to work and support their families. So, the benefits of early treatment are not under debate here, but rather the means to achieve them.

It is manifest from the medical records that a high proportion of patients are extremely slow in going to MSF France-run Clinic B. The interviewed patients, for instance, received HIV-related treatment a year and a half later on average, when there was already a strong suspicion of HIV. This suspicion stemmed either from their partner's disclosure of their HIV-positive status or from their own persistent symptoms of opportunistic infections. Here is a review of what happens during the lengthy period before patients take up the treatment programme.

2.1. WHERE DO PATIENTS GO FOR HELP?

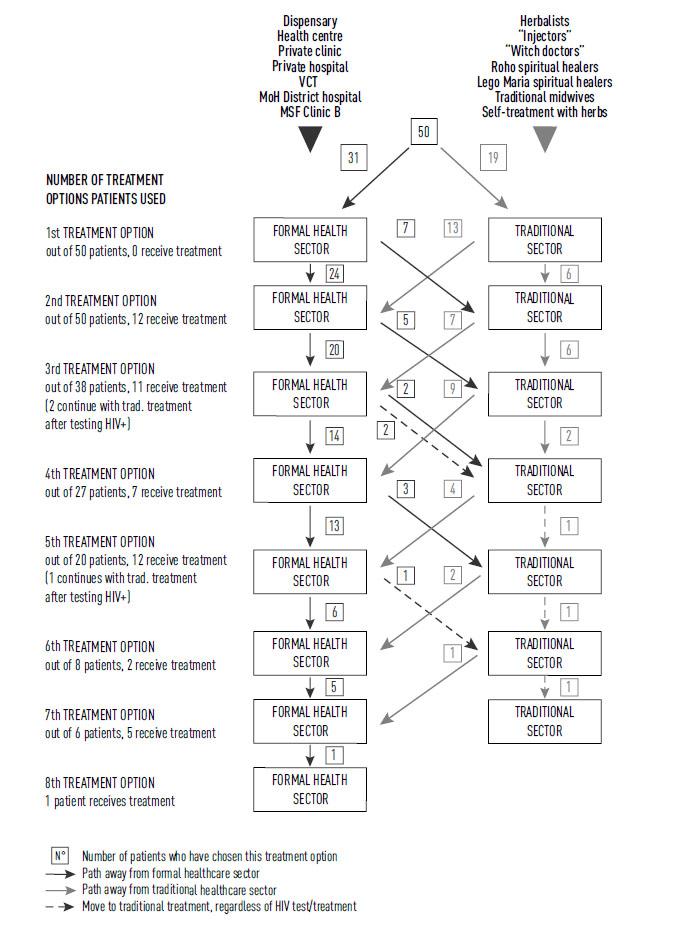

The diagram below is based on the analysis of interviews with 50 patients (25 male and 25 female); for more details on methodology, refer to Kovacic V. (2010), Operational Report I. Each patient's account was plotted as a set of pathways, joined in Diagram 1.

Analysis of the health seeking pathways (the steps that patients took and the treatment options they used prior to receiving HIV/AIDS treatment) gives cause for alarm. More than half of the patients (62%) began in the formal healthcare sector such as dispensaries, private clinics, district hospitals, etc. where they could be tested for HIV. Failure to diagnose patients with HIV during the first four visits to a healthcare facility was on average 74% (1st visit: 100%, 2nd visit: 68%, 3rd visit: 59%, 4th visit: 74%, 5th visit: 40%, 6th visit: 75%, 7th visit: 17%, 8th visit: 0%). Furthermore, over half (57%) of the patients had to take at least 4 different steps before receiving satisfactory treatment. The maximum number of steps reported before receiving appropriate treatment was no less than eight.

This leads us to conclude that, despite HIV/AIDS being a major public health issue in the area and that patients regularly access formal healthcare facilities, the ability to diagnose an individual with HIV in these facilities is extremely poor. Hence, the poor rate of suspicion (a clinician’s ability to suspect HIV infection) and diagnosis (lack of technical capacity) were major reasons for delays in treatment.

In spite of this, in comparison to traditional treatment, the formal healthcare sector leads the way in the health seeking process; patients’ flow is considerably higher (on average 19 patients per step) compared to the traditional sector (on average 7 patients per step). More than one third of patients (34%) turned to traditional health systems as a second option after becoming disillusioned with the ineffective treatment provided at formal healthcare facilities. But, out of the 19 patients who began with the traditional healthcare sector, 68% turned to the formal healthcare sector as their next treatment option.

In short, the formal healthcare sector is the leading treatment option chosen by patients when confronted with HIV-related symptoms. Poor diagnosis results in treatment that does not relieve symptoms. This leads to substantial intervals before the next visit to a formal healthcare facility and impacts on opting for traditional treatment as an alternative.

Diagram 1: Patients’ pathways (based on 50 patient accounts)

2.2. INSTITUTIONAL DENIAL

When the patients who used formal health facilities as the first option were successfully diagnosed, this was the end of their long health seeking behaviour. In relation to this, we use the term “institutional denial” to refer to institutional neglect and resistance (whatever the reason) to diagnose patients with HIV, even when the symptoms clearly indicate the likelihood of HIV infection.

Let’s look at the example of the patient who went to Ndhiwa district hospital District hospitals are at the top of the organizational structure of the local healthcare system. This implies they have far greater resources, medical staff and equipment compared to lesser health units. In theory, they are equipped to carry out HIV diagnosis and follow-up.with persistent diarrhoea. Despite being an obvious symptom of HIV infection, she was treated for typhoid for two years and was never offered an HIV test during her visits to the formal healthcare facility. Another example is a patient who, during a couple of repeat visits to the MoH division of Homa Bay district hospital (an extension of the MSF HIV/AIDS care unit) was treated for “serious malaria”. After a lengthy and frustrating period with no improvement in his symptoms, he was at last offered an HIV test.

The conditions most commonly treated early on in health seeking behaviour were malaria and typhoid. Not surprisingly, patients who were disillusioned with ineffective treatment turned to traditional methods as an alternative and it took them a long time to decide to return to the formal facility. This decision was also fuelled by a traditional explanation of diseases in the event of diagnostic failure in healthcare facilities: “If someone suffers from Luo diseases, tests in the hospital do not show anything in the blood”.

Hence, in contrast with reasoning delays in treatment with patients’ lack of urgency (ability to seek healthcare), improved HIV-infection testing capacity, insufficient in the formal healthcare facilities, is required in order to detect more HIV infections in the early stages of the disease.

2.3. TRADITIONAL TREATMENT

Despite the predominance of the formal healthcare sector, traditional treatment was frequently used by the interviewed patients (a total of 72%), and remains an important treatment option in health seeking behaviour. The following description provides some insight into the practices used and evaluates the conceptual interaction between traditional healers and the formal healthcare sector.

Traditional treatment is provided by traditional healers (“witch doctors”, herbalists, traditional midwives)While “witch doctors” and religious healers profess spiritual powers, traditional midwives and herbalists claim to have technical skills only, knowledge of herbs and abnormal physical ailments, for example and religious healers, mostly from independent churches Roho and Legio Maria. Traditional treatment involves drinking herbal infusions, licking dried herbs, using herbs for bathing, and superficial cutting of the skin and application of herbs. Spiritual healing includes praying, sprinkling blessed water over the patient, and drinking blessed water.

This type of treatment is associated with the diagnosis of two different traditional diseases, chira and witchcraft Chira is associated with symptoms of gradual weight loss, which in Luoland is attributed to the break with Luo customs and rites. Witchcraft, which causes skin disease, stomach disorders or abnormalities in the extremities, is attributed to witches, people with evil intentions motivated by jealousy.(more details on traditional treatment in Operational Report I).

In support of the criticism of the culturalistic approach, none of the interviewed healers claimed to be able to treat or cure HIV/AIDS. On the contrary, they were very clear that this is the domain of the formal healthcare sector (“hospital disease”, as they call it). Some of them, when they saw their clients’ symptoms, even said they suggested to them the possibility of HIV and referred them to the nearest healthcare facility. Therefore, in some circumstances, the local culture works in collaboration with, rather than against, the formal medical institutions.

III. CONCLUSIONS

Racial and cultural stereotypes have been used from the early stages of HIV/AIDS control to explain the specifics of HIV distribution in Africa. Unfortunately, the same principles are applied when healthcare providers struggle to explain poor access to medical facilities providing HIV-related care. Through the example of the health seeking behaviour of HIV patients who delay accessing HIV-related care, we see that culture, namely the traditional interpretation of symptoms and traditional treatment, is only a very small part of the problem in Homa Bay. In contradiction with common assumptions regarding patient and community culture determining care-seeking and delayed treatment, long delays in accessing treatment were mostly due to the failure of the formal healthcare sector to diagnose these patients with HIV when they accessed health facilities earlier in health seeking behaviour. This example demonstrates the need to conduct a critical evaluation of the provision of quality care in MSF’s operational area. It also opens up debates on the pertinence of our perceptions of programme beneficiaries and our assumptions regarding the cultural determinants of health seeking behaviours. A critical approach, based on evidence from the communities/beneficiaries but examined and analysed impartially without cultural stereotyping, would enable the development of effective HIV/AIDS programmes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ayikukwei R., Ngare D., Sidle J., Ayuku D., Baliddawa J., Greene J. (2008). HIV/AIDS and cultural practices in western Kenya: the impact of sexual cleansing rituals on sexual behaviours. Culture, Health & Sexuality 10 (6): 587-599.

Caldwell J. C., Caldwell P., Quiggin P. (1989). The Social Context of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 15(2): 185-234.

Ciao C., Mishra V., Ksobiech K. (2009). Spousal communication about HIV prevention in Kenya. Demographic and Health Research Working papers Papers 64: 1-30.

Gisselquist D., Potterat J. J., Brody S. and Vachon F. (2003). Let it be sexual: How health care transmission of AIDS in Africa was ignored. International Journal of STD and AIDS 14 (3): 148-161.

Kovacic V. (2010). Access for more – overcome barriers to access to HIV/AIDS care in Homa Bay, Kenya. Operational report I. MSF France, Mission Kenya.

MSF-France, 2009. Kenya Programmes –Medical Activity Report 2009. Nairobi, Kenya.

National AIDS control Council, Kenya. December 2005. Kenya HIV/AIDS Data Booklet. Nairobi, Kenya.

Ogoye-Ndegwa C. (2005). Modelling a traditional game as an agent in HIV/AIDS behaviour-change education and communication. African Journal of AIDS Research 4(2): 91–98.

Vaughan M. (1991). Curing their ills: Colonial Power and African Illness. Polity Press and Basil Blackwell Ltd., U.K.

Période

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed about our latest publications. Interested in a specific author or thematic? Subscribe to our email alerts.