Goma’s IDPs: a catastrophe in plain sight

Michaël Neuman

Michaël Neuman describes his visit to Goma’s IDP camps, where he spent two weeks. He shares his dismay at the low level of assistance provided by the aid sector, especially when we recall that the Sphere standards, born precisely out of the failure of the humanitarian response in this same region of Goma in the mid-1990s, were conceived and championed by all of us.This text was published on 13 June 2023 as a Mediapart blog post.

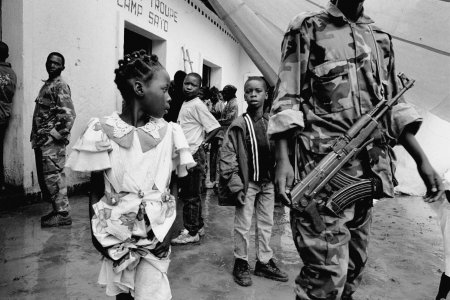

Goma, North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Since last year, hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people have arrived at the foot of the Mount Nyiragongo volcano, on the shores of Lake Kivu, fleeing the fighting that broke out in Masisi and Rutshuru Territories with the new M23 offensive. Amidst the tall grass and lush hills, the camps they occupy offer heartbreakingly little. Shelters that would give anyone nightmares, one meal a day at best, and long treks through the forest in search of wood to sell or build huts or cook with, risking violence and rape by armed groups or civilians.

These people have been there several weeks, or two, four, sometimes six months. They have nothing, and judging by how they live, you might think they arrived just a week ago. On the bright side, with the region entering the dry season there should be less and less rain causing less wind and rain damage to the shelters, fewer mosquitos, and so less malaria. These people must be brought to life, one by one – each of their stories, the individuals behind the statistics, their tales of violence, their villages bombed, their spouses gone, their families destroyed: the grandmother who takes care of her five grandchildren whose parents were killed in the attack on their village; the young mother of eight who must leave her youngest, still breastfeeding, all day while she goes searching for wood, recounting how she was whipped by the forest wardens. She can’t feed him until 5 p.m., the first meal of the day for a few-month-old baby. I also remember the old woman who described how she was knocked down during a food distribution a while ago now and lost some teeth; she went to get treated, and when she got back to her little shelter her bags of food were gone. Everyone says they eat only “by the grace of God”. The main source of household income is wood collecting, female prostitution, and, to a much lesser extent, day labour in town and in the fields. Without food inputs, there can’t be any market, so every kind of exploitation and abuse exists both inside and outside the camps. There are many, many children; their parents, especially fathers, are dead. There are far more girls than boys – the latter are often recruited by armed groups.

Little can be said for the performance of the so-called international “aid system”: broken promises, or more often nothing at all. How is it possible that people are still languishing in such misery four or five months after arrival? Half of a given camp’s inhabitants may have gotten a food distribution in mid-April but nothing since, while the other half may never have gotten anything at all. Sometimes, entire sites have been given no food or basic necessities, no tarps, since being set up in early February. Then the displaced show their frustration – sometimes with violence – with camp officials and aid organisations; some clashes are between the haves and have nots. People threw stones at a man guarding an MSF-supplied water tank, sending him to the hospital. What else would one expect? Some water delivery contractors stopped deliveries without notice, for lack of funding. While the aid operation has gotten better in recent weeks and the lack of water, latrines, and clinics is less severe, what there is still falls far short. Coordination of the aid is dysfunctional or non-existent; who does what, where? When will the highly anticipated distribution happen, if ever? No one knows anything – the camp residents no more than the aid organisations themselves. One old man bought a worn-out tarp full of holes for just over a dollar to cover the straw and wood hut he was living in with his four orphaned grandchildren. A new tarp costs between seven and twenty dollars, an amount far beyond reach for many. One nurse explained that the rainy season is a good time to rape in the camps, because the tropical downpours that regularly pummel the shelters drown out the women’s cries. The crisis resists indicators; epidemics are declining, but measles isn’t far away, cholera is still present, and malnutrition – while significant – cannot itself describe the scale of the catastrophe. Especially since these indicators are unable to capture the heterogeneity that exists at some sites. While it may be due to inequitable distributions, such heterogeneity can also be explained by where the displaced fled from, since it is easier for some than for others to go back to their home region, nearer the city, to get cassava and sweet potatoes. Lastly, pre-existing social inequalities do not disappear, and some of the displaced – lacking a network or expertise on how the city works – have more trouble finding the things they need to get by in Goma. At any rate, all the displaced have their own particular trajectory.

To qualify the catastrophe there is an indicator that, while of course not sufficient, is rarely misleading: do the children play? There are places here where the children smile and run, despite the disorder around them. And other places where their sadness is crushing, their eyes filled with bottomless melancholy, and they are visibly malnourished. They do nothing but wait, stomachs empty, for parents or older siblings who have gone to look for something to feed the household. Most of the adults and older children are away from the camps during the daytime, making it even harder to monitor the children medically.

But as striking as the hardship is the solidarity – between the displaced and from the surrounding villages – in the form of lodging and food and non-food donations, which helps keep the situation from turning into a large-scale health catastrophe. Here, an old lady on the street who has received a bit of rice, which a church was giving out to the most vulnerable households. There, it’s a former MP who made a food donation. Somewhere else, a youth organisation from Goma made another. Local assistance, often by individuals, is thus significant – which is a good thing, because if they had to count on outside help the displaced would long have been dying in large numbers. The Congolese government, on the other hand, is doing pretty much nothing.

It is also worth noting that the catastrophic situation in the DRC – a country that has been at war for decades – has become normalised in people’s minds and is now being called an “ongoing humanitarian crisis”. When catastrophe is everywhere, all the time, it ceases to be anywhere – even when the hardship and catastrophe have just taken on another dimension in terms of their size and level of violence. An MSF survey done at one of the camps in April concluded that violence – for the men in particular – was the primary cause of the high mortality observed in the displaced population from January to late April; that violence occurred both in the places they came from and on their journey to Goma. The most widely understood analogy here is to the big Hutu refugee crisis in the mid-1990s after the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. But we can get used to anything, probably. The result has been a slow, blunted, lumbering aid system, despite good intentions from some of the aid actors. Elohim, Nzulo, Shabindu, Rusayo…we recite the names of the camps and their population numbers: eleven thousand, eight thousand, thirty thousand, eighty thousand people. A total of more than 600,000 people for the city of Goma alone. These numbers are sometimes overestimated, but that’s not the point. There are huge numbers of people here who share, to varying degrees, a lack of prospects as they wait in extremely precarious physical conditions. No, this is not routine.

The vast majority of displaced people, from the Masisi region, are not even close to going home, so unsafe are the places from which they have come and so high are the risks to their villages, the risk of forced recruitment, the risk of reprisals, and – always – the risk of rape. Didn’t one female patient tell us, “I get raped in every war”?

While war- and insecurity-related constraints may impact the deployment of aid in the province, they do not exist in the city of Goma, and in any case cannot explain why the displaced are getting little or no assistance. Aid actors have a huge responsibility: helping these people at a particularly difficult time in their lives and helping them get through it. I have been doing this job for a long time, among displaced populations in particular; never have I encountered anything like this combination of a concentrated population, violent experiences, and inadequate humanitarian response.

To cite this content :

Michaël Neuman, “Goma’s IDPs: a catastrophe in plain sight”, 16 juin 2023, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/blog/camps-refugees-idps/gomas-idps-catastrophe-plain-sight

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute

Add new comment