Xavier Plaisancie

Doctor, graduate in tropical medicine. He began working with MSF in 2016 on issues related to access to HIV care for men in the Homa Bay district of Kenya under the supervision of Jean-Hervé Bradol and Marc Le Pape. This research will form part of his medical thesis, which will be published in a CRASH book. Then, in 2019, he joined the oncology project in Bamako, Mali, as a palliative care doctor and researcher on the trajectories of breast and cervical cancer patients. He worked with MSF in Kinshasa as a doctor in a ward caring for patients living with HIV at the AIDS stage. Since 2022, he has been pursuing a master's degree in the sociology of health at EHESS which, in conjunction with CRASH, has led him to take an interest in palliative care practices in Malawi and the development of the discipline in a humanitarian context.

Chapter 3 - Results

I. STUDY POPULATION

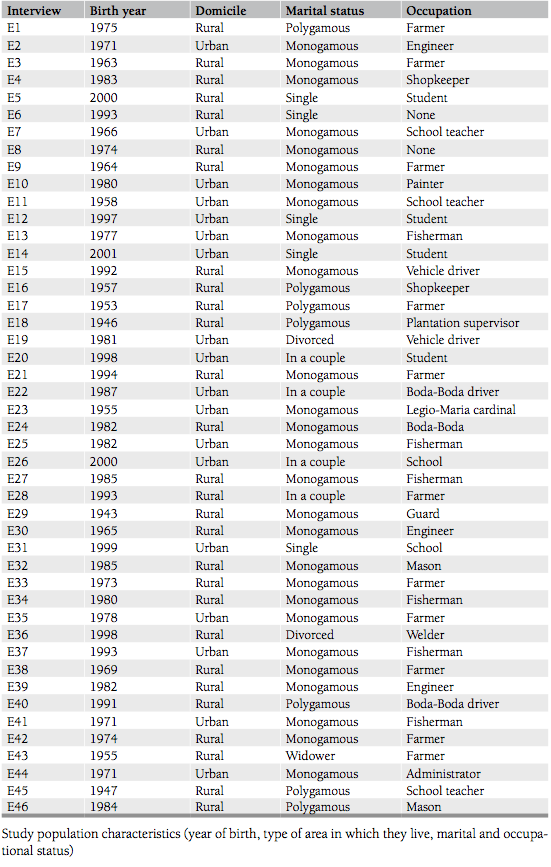

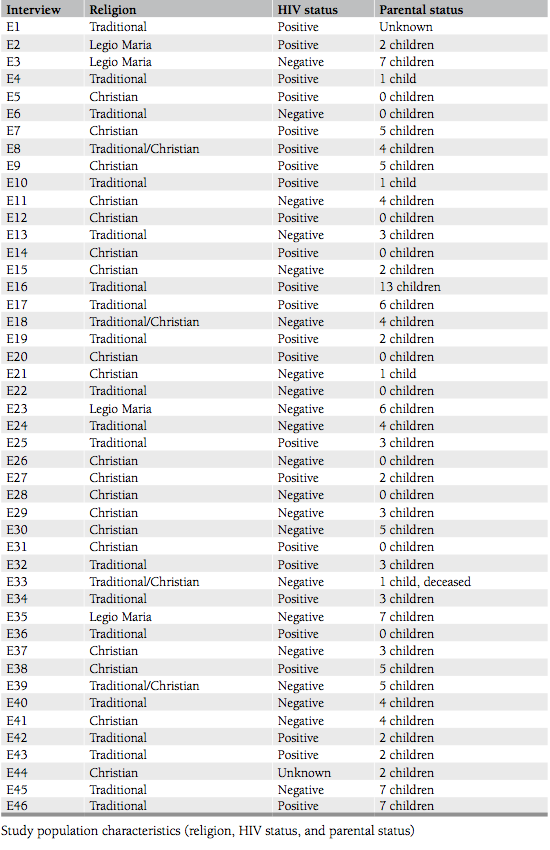

The mean age of the men questioned was 40 years and their median age was 37 years, i.e., their median year of birth was 1970.

In terms of marital status, 58.7% of the men questioned were married and monogamous, and 15.2% were polygamous with two wives. Another 17.4% were bachelors, widowers, or divorced. Finally, 8.7% were part of an unmarried couple.

In terms of fatherhood, 21.7% had no children, 23.9% had one or two children, and 37% had three to five children. Another 15.2% had more than 5 children. Finally, the parental status of 2.2% was not known.

In terms of HIV status, 53% were HIV-positive and 47% HIV-negative.

In terms of occupation, 23,87% were farmers; 13,02% were still in school or university; 13,02% were fishermen; 8.68% had mechanics-related jobs; 6.51% drove Boda-Bodas (motorcycle taxis); 6.51% were teachers; 6.51% were engineers (active or retired); 4.34% were shopkeepers, some of them also fishermen or farmers; 4.34% did casual work as masons, depending on manpower needs; 4.34% had management or administrative jobs; 4.34% were unemployed; 2,17% did religion-related work, and 2,17% were security guards.

As for the geographic distribution of the study population, 60.8% lived in rural areas and 39.2% in urban areas.

Forty-one percent of the study population described themselves Christian, 41% as traditional, and 8.7% as members of the Legio Maria movement, a combination of Christian and traditional practices.

The characteristics of the primary study population are as follows:

II. RELATIONSHIP TO EDUCATION AND WORK

A. UPBRINGING AND FORMAL EDUCATION

Fathers are supposed to instill certain values in their sons, in particular regarding their family responsibilities and the need to start a family in order to carry on the family name and to become the head of family should the father die.

“Much of my time, like often in our culture, boys are given the education by the father, how to take the family responsibilities, to be concerned when they grow up”. E11

Some Luo feel that such teaching has changed, and that parents and grandparents are less interested in bringing up the younger generation, and at the same time that children and adolescents have lost interest in what their parents have to teach them:

“You see the grand father is teaching mostly how they should behave in the society. The grand mother is supposed to give the same message to the girls, “you should take care of yourself, you should not do this, you should not do this….” Things have changed, these old people don’t take interest in that house, not like before.” E30

Though masculinity had, in the past, been defined based on physical attributes, parental upbringing seems to have gradually placed more value on intellectual pursuits, or at least those requiring more education. Thanks to access to education, views on what used to be considered a sign of masculinity and the clear distinction between female and male roles appear to have changed:

“But when we look at how things change, as this people don’t go to work physically, so there is not much about men being a warrior, they defend the family, they are believed to be the strongest. So there is a little change, because of the education.” E11

Among the youngest patients we questioned, formal education is now a source of social recognition. They associate sexuality with marriage, which is itself associated with having children, and such a life plan is possible only for men whose financial status and employment situation are sound. Hence education allows access to parenthood, and as we will see, to a form of social recognition:

“I would like to, after finishing my school, maybe apply for a good work, then I marry, then I have children that is my plan (…) it is better to get married after education, when you have get a good job for you to get money to protect the family, the children” E31

In an economically difficult context, some young become concerned with finding a source of income that will at least allow for their family’s survival, even if that means sacrificing formal education – in particular, when parental support for the family declines or evaporates completely. Indeed, the loss of parental support forces some young men to shoulder the family’s financial burdens:

“We lived in peace in a good way, my father died. Now, I am the remaining leader of this family (…) The money was not enough it was less than one hundred schilling. That stopped me from doing my class exam. I continued struggling to support my mother by going fishing.” E27

Thus the situation is more complicated for young men forced to become the head of household early, who must sacrifice formal education, which is increasingly important socially and offers access to gainful employment, which is rare in this region. As a result, they must resort to lower status, lower-paying physical labor.

In the population surveyed, participants who studied for longer and then got a job related to their studies reported having had a religious upbringing or being exposed to strongly Christian messages. In contrast, the men doing physical labor – farmers, for example – tended to report a traditional family upbringing. The religious talk dealt, in particular, with intentionally limiting the number of children. This gave some of them access to higher income, which could allow them or their children to pursue more formal education. For many, adhering to Luo traditions made it impossible to educate their children – regarding formal education, in particular:

“That is the Christianity, so when people perceive this and live the Christian way, many men at these days said ‘I can see that polygamy decreasing‘ (…) maybe the Luo men they tend to be polygamous, it is like they are feeling that it was also a sign of wealth before (…) you are even more wealthier so people used to compete for having many women and many children. And now it is a problem because you can see the flour is two hundred, one cage of sugar is two hundred, now what to think if you have 40 children, it is stress, it is more hassle.” E44

B. RELATIONSHIP TO WORK

According to the men we met, there is limited work to be found in Nyanza Province. Most of the jobs are in agriculture, fishing, and trade. Jobs requiring more years of study – such as engineering or teaching – are limited. There are few employment opportunities, and so access to university or a lengthy training program in no way guarantees a job in the region.

Despite the changes in young men’s upbringing and access to work and the importance of formal education to social status, one thing seems not to have changed: the quasi-constant feeling among the men we met of being responsible for their family’s survival and wellbeing.

Difficulty finding work can lead men to defer plans like marriage, which is in turn associated with having children. Indeed, marriage and children require sufficient income:

“I was planning for mechanics but I can’t go because of the financial problems. So I am still waiting and I can’t marry right now. Because for marriage I have to spend more money, provide for her, build a house…” E28

C. SEX EDUCATION

At adolescence, girls are taught the value, primarily moral, of their virginity, as it is a source of family pride. Aside from its moral value, virginity also ensures a higher dowry. Transmission of such values has tended to change, and virginity is not protected as strongly as in the past. Yet several men report having commended it to their children:

“You know the values of African cultures, the values that are still much respected like, when a girl is married with her virginity, it is pride to the parents and the community, though today you find a break of those values. But we still teach them about the importance of those values.” E7

Young men’s virginity is protected for different reasons – above all, to ensure that they can continue their formal education, which would be threatened by beginning their sex life early:

“They believed too that having premarital relationship would ruin your future in term of concentration in your studies, you are diverted, so that is the reason they wanted us to focus on one thing, so if it was school, just school and they advised that it is not bad to have a relationship but after you achieved your education.” E7

Boys currently seem to enjoy relative lenience when it comes to monitoring their sexual behavior, which is better known and accepted. When the subject of young people’s sexuality did come up, it was often in terms of early female sexuality and the socioeconomic explanations for it.

In the past and still, to a lesser degree, today, children were taught via prohibitions voiced by their parents – by fathers to their sons, in particular. Children were told they would bring a curse on the family should they violate the rules of behavior. Some of those rules applied to sexual behaviors, others governed everyday family relationships. Traditional prohibitions and recommendations seemed, according to those surveyed, to apply particularly to males. Hence a parent-child conflict could bring a curse upon the family home; among the dangers was the threat of a curse on any future homes set up by a family member on the family land. That curse has a name – Chira – and is believed to affect individuals who fail to follow the rules of behavior imposed by Luo society. Chira manifests primarily by weight loss, and ultimately leads to death. The threat of Chira seems to serve as a means of moral control over sexuality by dictating the behaviors – sexual, in particular – that young people may or may not engage in:

“Chira is when one do a taboo, which is not accepted in the society, or it was something which was not supposed to be done according to our traditions (…) Even the prostitution, one is not supposed to have sex intercourse with somebody who is not his wife. They could tell you “he has Chira”, so it was a form of teaching.” E11

When the subject came up, subjects cited male behaviors to explain the occurrence of the Chira curse.

Such beliefs tend to disappear gradually from one generation to the next. Nowadays there is some doubt about the danger of Chira when certain rules are broken; for some, it has been replaced by another threat – HIV:

“Before you could cheat somebody that “you have Chira”, but he had AIDS. HIV and Chira are two different things. HIV is AIDS and Chira is a traditional family disease.” E27

Christian values and medical messaging on HIV have tended to supplant, or even condemn, traditional Luo beliefs, which were perhaps a way to control behavior. Traditional education and prevention messages are being replaced by several other sources of knowledge – school, religion, and medicine – conveying different ideas:

“They are unsaved. Those who are not saved talk about Chira, but with the saved we have not talked about it, we don’t build our faith on it (…) When has it changed? After the teaching. By the Community Health Worker, in the community, and the health educator.” E38

Schools seem to deliver a relatively ambiguous message. Abstinence until marriage is strongly recommended, but condoms should be used if sex is “necessary”. Not only is there ambiguity about what determines whether sex is necessary; the men reporting these messages failed to figure out younger men’s motivations for having sex, assuming that peer pressure was primarily responsible for that type of behavior:

“I told them about the need to hmm… to be… to avoid sex… Avoid it completely. We call it abstinence. Because they are still pupils. So they should not think about sex at their age… we teach them ways of protecting themselves from STI (sexually transmissible infection), one of them is abstinence, another one is the use of condoms, if it (sex) is necessary.” E7

Teaching girls about condoms was seen as inconsistent with teaching them value of virginity. These messages coexist more easily for boys, confirming that girls’ sexuality tends to be limited and that of boys more accepted.

The message about condoms is sometimes hidden, and often reserved for boys:

“I teach boys how to use condoms. And girls? Yes but it is mostly the boys who use the condoms, in fact we demonstrate them openly how it is supposed to be use and the rest. To the boys.” E30

Hence boys have sole responsibility for condom use:

“Only the man we propose. Every woman I have met I didn’t see them propose I don’t know why (…) According to me I always have to propose. It is the responsibility of men.” E37

Some men were having difficulty, and reported having to negotiate condom use and being met with refusal or misunderstanding by their female partners, as in this case:

“She didn’t want to use condom and she hate the condom, I could not even find them in the house (…) Where I put them in the box in the house, I could not find them. Even the box I could not get (…) I asked her ‘why you don’t want to use condom’ then she spoke a word: ‘those ones are for dogs!’ Maybe this is just to stop me, to ask no more questions.” E19

D. IMPACT OF EDUCATION ON BEHAVIOR

There seem to be two schools of thought regarding education’s impact on behavior. The older men, who received sex education – whether traditional or Christian – before the HIV epidemic, seem to have been more sexually active prior to marriage than the youngest, and were possibly at higher risk. For the youngest men, it seems to depend on the type of prevention message received. The message based on abstinence and condoms seems to be more efficient. Among the youngest subjects, condoms are an option for those who will not consider abstinence. Fewer of them seem to respond to the abstinence-only message, whether it comes from religious or educational institutions or from the family. And the medical message seems to carry the greatest weight.

III. RELATIONSHIP TO WOMEN AND FATHERHOOD

A. VIEWS ON PREMARITAL SEX

Despite individual differences, at each “stage” of male life the importance of reputation forms a backdrop that often seems to condition specific behaviors. Education and access to high social status are of the utmost importance; this was a major concern and a central topic of discussion.

Being sexual and having numerous partners are particularly valued by young boys, as is the ability to have these types of relationships. There is peer pressure on young men to be sexually active as early as possible. This is associated with reputation, because some link it closely to masculinity itself. Thus being a “man” is associated with early sexuality, sometimes leading to sexual competition among adolescents. Among the men we questioned, this pressure was not confined to a particular social class and seemed to happen both in and outside of school, and in certain work settings.

“In the past we used to talk about girls (…) competitions about how many girls we can have again, if we can seduce, if you can seduce girls and things like that (…) when you abstain, somehow young fellows see you as somebody who is a coward (…) So that’s where you are sure that you are men, capable of that.” E37

Some rejected such behavior once they became aware of HIV. Some gave up or changed their social relationships in order to avoid that pressure and that type of behavior:

“I could have such character if I would have interacted like them. You can be involved under pressure, if you are close to them, you listen to their conversation and you will be lured to get into these acts (…) That is why I am not close to women (...) I don’t like it that is why I don’t have friends.” E15

Rejecting sex as the only means of social recognition, others found a way around the reputation problem without altering their social relationships, placing value on other behaviors and avoiding situations that might involve them in sex too early:

“I was respected at school because I am a celebrity at school (…) Some have sex just because of the pressure (…) But sometimes it is fashion to be virgin (...) what I’ve come to realize, they wait for boys to come to ask. But no, when she comes and sometimes we meet, I come up differently she cannot even think of it.” E20

B. MARRIAGE

While the discussions and concerns of younger men leaned more toward sexual competition, there came an age where recognition by others, a sense of personal accomplishment, and even masculinity required being married, which was in turn associated with having children. According to many, that pressure generally started not when they reached manhood, but between ages 20 and 25; some adolescents planned to get married around that age. Young men who had had multiple partners in the past felt pressured by their friends to get married and change their sexual and relationship behavior. The feeling that they were unable to get married, however, prompted them to put it off, to avoid the problem:

“You know a lot of my friends, they use to tell me, “why don’t you marry?” (…) Them they are married (…) They only want me to get married. You know when you are a boy from age twenty to twenty-five you need to be married (…) According to them, it is important. But to me, you can’t get married if there is no mean to provide for her. To be a man you have to get married in the community. No even it is not a shame, but you are someone neglected, that you are not a man, such thing like you are mad…” E28

Some men rejected that pressure, but their rejection was often partial, or temporary, and the men found other ways to satisfy their community and their own desires by showing that they were involved in a single relationship, as a way of shielding themselves from other people’s judgments.

“So they tell me “are you afraid?” “no I am not afraid, I have a girlfriend you know” (…) I already told her, I didn’t propose but I just tell her “now I am not ready to marriage but if you can wait for me two or three years to come…” E28

Despite a positive rejection of marriage, some individuals found the pressure too strong, due in particular to the personal importance placed on descent and perpetuation of the family name. That value was also transmitted, indirectly, by their upbringing, whether traditional or religious. One man, for example, separated from his first wife, initially refused to remarry. But coming from a traditional background, he felt indirect pressure from the community to have a child. Because he had recently converted to Christianity there were also religious principles at play, pushing him to make fatherhood a part of the marriage he had rejected initially:

“The perception which I have, sincerely, if it were that women are not to be married to give birth and give the family to continue, it is better for one to stay alone, to be unmarried (…) When I see my friends around, they had family, but I did not have family so that notion forced me to get another wife to live with, to have continuity in my family I should also have children, to have someone to be…to live behind me.” E8

The men who reported pressure to marry from their friends, family, or community usually came from a rural, traditional background. They seemed to have less lucrative, less secure, and more agriculture-related jobs, in particular, or jobs requiring less education. Men from other backgrounds with a religious upbringing tended to give more personal – i.e., financial, health-related, or spiritual – reasons for marrying. The men with the most advanced education did not mention this pressure, or the importance of passing on the family name, or that they needed to marry so that their younger brothers could marry in their turn (as seniority dictated). Moreover, pressure from family and friends did not seem related to age. Both the youngest and oldest men described that pressure.

C. MARRIED LIFE

The men we interviewed said that their concerns changed when they got married. Discussions changed and they became less interested in relationships with women. They became more oriented toward being able to ensure the family’s wellbeing, and particularly that of their children, by finding a stable, adequate source of income. As mentioned above, ostensibly “male” family responsibilities were instilled from early childhood. Many of the men described their role as the economic mainstay of the family:

“Of course there are differences. One even that I have a family now I have more responsibilities that I have to do (…) I have a role to play with my family. I take care of my family that is the role. I see how they can feed how I can get some money to take children to school” E2

Traditionally, women who failed to fulfil the role assigned by society or behave as their husbands wished may have been cast out of the home, but “combined” with another woman, the couple entering a polygamous relationship.

“But today, population has grown, you don’t have that vast land to keep the cattle so it is not really valued today but depending on individual circumstance, you can be forced to be polygamous, maybe if you don’t have peace in your family, with your first wife, or maybe she ran away.” E7

In addition, it was often said that polygamy was considered a sign of wealth, because it showed that the man could bear the financial burden of numerous marital relationships.

“I don’t know how our traditions, if you have many women you are wealthier, if you have many children, you are even more wealthier (…) You will be considered in African culture then, traditionally if you have many women and children, to be somebody…” E44

This practice is being challenged by current economic problems and moral condemnation by religious, governmental, and humanitarian institutions, particularly in the context of HIV:

“I can say things have changed, because we realized previously, men used to have 4-5-6 wives, but of late and because of the economic situation, getting some boys with two (wives) is a problem. And you see the problem of having many wives, they are more at risk than one wife, maybe things have been a problem.” E30

D. REPUTATION AND COMMUNITY TIES

Respectability and responsibility go hand-in-hand. As mentioned above, there is social pressure on young men to have sexual relationships, and then there is societal and self-imposed pressure to marry. The pressure there comes from how the man is seen by others, and respect from his peers depends on his ability to fulfil his duty to his family, single-handedly:

“In my family, my community, people, not like those who are rich, when you are poor they enjoy, because now you cannot have earning and living and you depend on others, but when you provide for yourself, they respect you.” E34

Men who are unable to meet their family’s needs risk losing their reputation, especially if they ask for help from their family or community. Men are considered responsible for supporting their family financially. This idea seems to be shared by both men and women alike.

E. FATHERHOOD

The connection between respect and fatherhood is still quite strong. In this population, becoming a father is a major event in a man’s life – a source not just of personal happiness, but of peer recognition and membership in society as well. In contrast, couples that cannot conceive and men who are still single beyond a certain age are to some degree excluded:

“In the area I don’t now have shame that I did not have children. Shame not to have children? You are not respected when you are not married and you have no children but your age mates have family and children. So you will not have respect. To be a man you need a family. The other responsibility or resource that you are a man: if you have a woman and then has not given birth to a child then you make her pregnant then she has a baby.” E40

For some, fatherhood was a part of marriage, never outside it. Not being married was equivalent to not having children. Fatherhood was, however, jeopardized by their economic and, as will see later, health situation. Fatherhood, a source of personal accomplishment and community respect, is now being reconsidered in terms not of its foundation, but its configuration. The Luo agree that having a large number of children from several different wives in a household was traditionally considered a sign of wealth and masculinity. But this view is changing, and some of the practices that define masculinity in this society are being rejected:

“And now it is a problem because you can see the flour is two hundred, on cage of sugar is two hundred, now what to think if you have 40 children, it is stress, it is more hassle” E44

Economic difficulties led to different behaviors as people attempted to adapt. Rather than wanting to have lots of children, formerly seen as labor power or a long-term economic investment, some now want to limit the number of births to reduce child-related expenses. This is another rejection of traditional masculinity – or the typical practices, at least – in favor of an image of men having control over their own sexual, family, and economic lives, being independent of the community, and meeting the economic, educational and health needs of their children:

“I wanted to have three. But now my income has not reached the level I expected (…) I want to have children but my income cannot allow me (…) One of the challenges is to have food for the family, the woman has to be dressed well, the child also has to be dressed well (…) It is not a threat to my life and it does not affect my reputation in the community because I know what I do.” E21

F. RELATIONSHIPS TO WOMEN AND MONEY

Whatever the man’s relationship to women, there was a connection to money. Relationships ranged from prostitution to marriage, including casual encounters and stable non-marital relationships. This connection was mentioned especially by the youngest men, for whom money is a necessity regardless of the woman or relationship type. There is a hierarchy in the responsibilities that men think they must fulfill, depending on the woman and what they expect from the relationship. Prostitution, which is by definition connected to money, does not require as much financial investment as marriage, for example. Then there are casual encounters that are automatically a financial burden for these young men, as they have to buy gifts, for example, for the purpose of seduction:

“You can also give a girlfriend a gift, it is not easy to give money when I don’t know how the money is going to be used, but the money I have, after time, I can spend them on.” E22

Before a man can get married, he must be able to shoulder the financial responsibility; this principle is instilled from a very young age. He must apprise his current or future wife, or her family, of his financial background. After paying his in-laws the dowry, money earned is invested in the marital relationship, strictly speaking, but there is still this notion of male responsibility:

“There was a change when I worked before I married; my girlfriend was the lady I used to be close to, so I gave her money, she used to give to her parents. Since we are married the money we have, we spend in our house, to upkeep us” E15

Apparently, this connection to money has not always existed. This man reported that current society is different than what he experienced in the same place in his youth. Relationships with women have apparently changed, and are more connected to money these days than they were before. Some of the older men tended to view the present connection to money as no different than prostitution, regardless of relationship type.

“During that time there was no use of money as it is right now that women I give them money. Right now they give money to women. You might have a lady and you talk with and after short time she observes how much you have in your pocket and then she goes with you and that is why people have to go testing so much because you don’t know the lady that you have contact with is well or not (…) I have been a watchman up to the bar and I have experienced how prostitutes behave.” E29

Yet in the interviews, these connections seemed to be multifaceted, between sex and money, love relationships and money, and marriage and money. Some subjects felt that young women used prostitution as a way to get the necessities, or to continue their formal education:

“For example, there is a problem even in university right now where they pay a lot of money, girls cannot raise because education at the university is payful and also what they need. So you may find a girl may have a boyfriend or what you can call a “sugar daddy”, so they may lure the young girls because they have a lot of money, or a lot of thing, and definitely this is prostitution. You know girls are more vulnerable, and also very weak when they are not properly cared for.” E11

In their opinion, by delaying marriage for any reason men risk losing the relationship, which would be threatened by other men more comfortable or more inclined to provide for the woman financially:

“Because for marriage I have to spend more money, provide for her, build a house … No, maybe this credits… “send me credits”… to go out. Well, girls always say yes but she has another plan... Yes, she could meet other men, you know… women love money” E28

Associating the idea of prostitution with relationships based on money, whatever the arrangement –with all that implies in terms of moral judgment – was more common in the older men. As mentioned above, they emphasized how different things were in their time, and in their past relationships with women. With the younger men, the monetary relationship seemed different and worked in different ways, although prostitution was not unknown to them. Many of the relationships, which took a variety of forms, had a monetary connection but that connection seemed as much self-imposed as demanded by the women. Note that the men who mentioned this monetary connection in their relationship – premarital relationships, in particular – came from more modest, and often traditional, backgrounds.

IV. ACCESS TO INITIAL INFORMATION AND HIV AWARENESS

A. ACCESS TO HIV-RELATED INFORMATION

1) The media

The men questioned got their information on HIV in a variety of ways. Many men got information via the media. This included reading newspapers and books about HIV, or more commonly, listening to the radio. Radio seemed to be an important source for first learning about HIV or getting further HIV-related information. The men who said they discovered HIV in this way were no different in terms of their urban or rural origins, their age (although most were born in or around the 1970s), or their religious affiliation.

Those who described getting their information from scientific articles, the radio, or books seem to have had a higher level of education. The oldest men more commonly described getting information from the media in general. Those from a rural background were more likely to get information from books about HIV, for example, but not from the radio.

2) Learning about HIV at school

School was another source of HIV-related information, but it was not a major source of information for the men questioned. Those who described getting information at school were among the youngest, born in or around the 1980s. Indeed, the youngest men got a lot of sex-related information at school. Was it, however, the first contact with HIV for most of them? That does not appear to be the case.

3) Learning about HIV from community-based public health campaigns

Another group of subjects said they first learned of HIV via interventions by medical or governmental institutions. This subset was small. Others first learned of HIV from discussions with their entourage – their family, in particular – or with community members; some even said that they had “heard talk” of HIV around them. The last route was among the most common, and was fairly specific to men from a rural background with no Christian influence, who claimed to adhere to Luo traditions.

4) Learning about HIV from direct contact with the disease

A significant subset of men reported having lived through the start of the HIV epidemic and witnessing its rapid spread and the severity of the symptoms once the infection broke out, and its high mortality rate. They had closer or more remote contact with the disease: seeing loved ones infected, seeing other individuals infected with HIV, or seeing the bodies of patients who had died from AIDS. For nearly all of those men, seeing such horrors seems to have given them a more acute awareness of the HIV problem than the rest of the men questioned. They were more likely to date their awareness of HIV, their initial questioning of their practices, behaviors, and/or test-seeking behaviors to the moment of their first contact with the disease:

“In 1989 when I saw HIV positive patients with the rashes on the body, thin person (…) During that time when you see somebody like that who is HIV and AIDS when you go to the hospital, the way he looked, and then to know that is how every patient look like it is terrible…it was terrible to me (…) I was afraid to have any other sexual intercourse and partners and that is why in my life even now I don’t have any other partner. So I don’t get HIV.” E3

B. HIV AWARENESS

1) Awareness process

While the experiences that raised subjects’ HIV awareness were as varied as the routes by which they received HIV-related information, those experiences were distributed far less evenly in the population questioned.

a) Gradual HIV awareness

Most of the interviews suggested that the awareness process was gradual, with the first contact acting like simple HIV information with no major psychological impact. A second, different contact via another source of information then confirmed the veracity of the initial information, which was often doubted at first. Those who had never seen HIV’s effect on human beings and those who had prejudices about the origin of the virus or the populations suffering from the disease had been able to deny the existence of HIV or their own vulnerability to it:

“I had just the belief that it was for other people. I did not imagine it could come to me because I had my wife and that woman. So I think I was just cheated (…) that it is not around here, it is far away. Yet I was right living in the infection (…) Yes I was aware it was there (…) Prostitutes in the bar, I thought, but it was for everybody.” E7

For them, the awareness process seems to have required more time and greater exposure to signs proving that there was indeed an epidemic going on around them, via successive contacts with different sources: school, the media, community-based interventions, and newspapers. Some men, after having questioned the very existence of the disease described on the radio or by outsiders, were forced to acknowledge its reality after learning that people close to them were HIV-positive:

“I used to hear in the announcement before I saw anyone infected in the village. I heard one of the man or the ladies was infected. So this one, it was the proof that it exists.” E1

b) Sudden awareness

Discovering HIV through school, family discussions, or community-based HIV activities (especially at a time when the younger generation is challenging the legitimacy of those institutions), did not seem to have an immediate impact on future behavior, but served merely as a first contact with the disease. In contrast, experiencing it up close had a greater impact and made men more determined to deal with it. A significant percentage of the men questioned said they first truly became aware of HIV (as a disease that actually existed in those around them, or by a recognition of their own vulnerability) when they saw its effects on the human body.

This mode of contact with the disease was reported by men of all socioeconomic backgrounds and religious preferences. The older men reported this more frequently.

c) Awareness upon diagnosis

A significant number of men had their HIV awareness raised by their own diagnosis. Patients who described this “late” awareness had gotten their information primarily through family or community discussions. Some had tended to consider the epidemic as remote, and did not necessarily connect the sick people they saw with HIV:

“In the 1990s (…) Some who went to work in town died and when the bodies was brought home, they were wrapped in polythene so we were told that the disease killed them, that we could not touch them (…) So you did not fear HIV? Because it had not been affected in my family (…) It was not a rural problem (…) I did not have faith that I could be infected (…) I thought it was just a simple thing, a disease which was not common in the rural area.” E38

2) Impact of awareness on behavior

HIV awareness had an impact on several levels. Some men got tested, stopped having sex or had it less often, or changed how they had sex, in particular by using a barrier method of protection. Those attitudes were modulated by a number of factors.

a) Gradual or sudden nature of awareness

Sudden awareness occurred when HIV’s effects on infected patients were not previously unknown. In such cases, subsequent behavior tended, at first, toward a radical change in sexuality.

When awareness was more gradual, men adopted a wider range of prevention behaviors. Most had themselves tested, in combination with another prevention measure. Many adjusted their sexual behavior, but in a less restrictive way than the first group – that is, by using protection, rather than by having no, or less, sex.

The repetition of prevention messages appeared to have a more lasting effect on behavior. It seemed to attest to the reality of the HIV epidemic and the veracity of its effects. As a result, new awareness was accompanied by better knowledge about how to avoid getting the disease. An analysis of the impact of information dispensed by schools and via loved ones or community-based interventions, when awareness occurred at that moment, showed similar results: most of the men used barrier protection, without giving up sex or modifying their sexual habits. However, further interviews showed that the use of such protection varied over time, in conflict with the desire to have children, itself associated with marriage. Some men saw marriage as protective, and used it as their sole defense against HIV, without other safeguards like a screening test:

“Most of the things I continue to learn them at school (…) Like myself, to have a child is on my mind, so that is why I cannot use condoms always. The first lady I did not use condoms.” E33

b) Religion

The use of barrier protection was most common among those who were more religious and/or more educated. It was less likely to be used by Christians, however, who believe in the protective value of God and marriage and have issues with condom use itself.

c) Proximity to the disease

Seeing a loved one suffering from the disease had a different impact than seeing “strangers” suffering. Men who saw a loved one with the disease were more likely to have less sex than those who saw it affect people with whom they had no emotional ties. Men who were not very close to any HIV patients were more likely to resort to testing alone.

d) Age

Older men and men who were already married when they became aware of HIV saw getting married and being faithful to their wives as a means of future prevention. The older men tended to start by being tested to ensure that they were HIV-negative, after which they relied on their faith in the protective value of marriage, and on giving up any extramarital sex, for prevention.

Most of the young men started by changing their sexual behavior, and then got tested afterward. With them, however, it all depended on marital status. Among the younger men who had not yet started having sex, awareness prevented some of them from having premarital sex, which was protection for them. Among those who had already begun having sex, the behavior change was more gradual, and often less restrictive. They tended change their sexual habits – a more or less satisfactory adaptation in terms of risk – but did not stop having sex completely:

“No I didn’t stop immediately even though I had the message but I still went on but this time round I was really, really careful. I used protections, at times I was at least bit by bit abstaining (…) you see, as we were competing. As teenagers we were competing (…) but now (…) maybe if I could only have one at a time. So I had to at least abstain or have one partner.” E37

Formal education, which had an influence on the youngest men, emphasized abstinence and condom use, either as a first choice or if abstinence was impossible. Some considered the abstinence recommendations unrealistic and rejected them. Here is one explanation by a young man:

“As teenagers we were seeing all the older people that they want to tell us the things which are not good but they used to do it (…) we believed they used to do it so it’s like there are telling us what to do, it is hypocritical so we never heard of them actually.” E37

3) Negative impact of awareness

With some men, learning that HIV infection could be fatal was a shock, but led to inappropriate reactions, with fear causing inertia when it came to prevention strategies:

“There was at time in radio “HIV is dangerous for your life”. It was advertisement through the radio. When I hear, I feel sorry because I pressed the God the world is over (…) When I go to the Bible (…) getting when the world will end so many diseases will come. I think “time has come”. Time was coming slowly, slowly we are now with thing dangerous from America that were coming here in Kenya.” E24

This type of reaction was seen with most of the modes of receiving information. It was more common for men who had had no prior information on HIV, prevention, or testing, and or whose initial contact with the disease involved a death.

V. REPRESENTATIONS AND PERCEPTIONS OF THE HIV RISK

A. CATEGORIZING RISK

When the men first received information on HIV, depending on how they received it, there was a tendency to blame the epidemic on different segments of the population.

For many, Christianity was not compatible with the persistence of traditional practices, as the latter would be fundamentally at odds with religious principles. Yet many of the men questioned did not choose between tradition and Christianity; while claiming to be Christian, they continued some of the practices condemned by Christianity. There was a distinction between “good” and “bad” Christians, depending on their adherence to traditional practices. Some felt that those who failed to reject such practices were false Christians who affiliated themselves with a religious group out of necessity, because they feared the potential impact on their social status of “rejecting” of Christianity.

“When you come from that family who are persistently not leaving the past, they want to follow the fathers request, they may not let you go so much easily. As much as they are Christians they may be Christians on Sunday or Saturday but the rest of the week they are not Christians (…) if you die the first question will be, “where do you want to be buried ?” (…) so everybody want to belong to a church.” E44

The “false Christians” who continued to adhere to traditions were considered a danger to the populace, due to the HIV risk associated with traditional practices:

“And also what they fear is the public image, the public relation. Right now the level of Christianity that has led people to know that wife inheritance [The expression “wife inheritor” refers to the practice of levirate marriage, that is, a man’s obligation to marry his brother’s widow] socially it is becoming a vice. And when we are in charge the way the messages have been spread, it is like a vice. When you see it, we call him these days a terrorist. If you are called a terrorist, you are a quite vile wife inheritor so they fear those names (…) They must feel very guilty, they are called terrorist…” E44

Hence Christianity was seen to have protective value of against HIV, and the risk of HIV used as a way to convince men of the benefits of respecting Christian principles and converting:

“I preach about HIV and AIDS. We must take care of ourselves so that you may protect yourself because in the church we are not all saved there is some who come only to listen to the word of God but they are not saved so we have to tell them there is a serious disease called HIV AIDS.” E29

When talking about young men and older men, that is, men between the ages of 16 and 80 years, there seemed to be a contrast between the sexuality of the young men and that of the old men; that contrast was quite striking in the interviews. For most of the men, sexuality and its representations changed throughout life, from a more competitive sexuality in the young to a more fatherhood-oriented sexuality as they got older. Accusations were mutual; to those in one age group, the other age group’s sexuality seemed less controlled and more morally reprehensible. According to the older men, economic insecurity, recourse to mostly female, but also male prostituting themselves, or Western cultural influence explained the young men’s high-risk sexual behavior.

“If they have little activities to engage them, their last resort is maybe have sex, just sleep. To get some resources, something to keep them busy, even apart from. You know when you get that money, maybe that money can also make you to start some enterprise, so if you can start some income activities, some business, that can build up in the process and will sustain you very well.” E7

The younger men, on the other hand, sometimes saw HIV as linked to traditional practices or to an earlier time when the epidemic seemed more serious. Hence the younger men associated HIV with older people:

“We knew it but we took it as just a normal thing we knew it was the disease of older people so young people don’t realize, we knew that but as we grew we learn that it is real.” E37

It is undeniable that the men interviewed tended to connect high-risk behaviors to membership in various social categories based on age, occupation, beliefs, or sexual practices, and that that connection was narrowly and firmly established. Some blamed the illiterate, single people, or fishermen; others blamed the Boda-Boda drivers.

B. PERCEPTION OF RISK

Some of the men (those subject to Christian influences, in particular) felt that the more traditional population engages in higher-risk sexual practices. That prejudice is based on their assumption that the more traditional population engages in sexual practices like polygamy, levirate marriage, and sexual purification rites and more widespread prostitution. In their view, belonging to that segment of the population equates to a higher risk of being infected. The idea that traditional families engage in more unrestrained sexuality leads the latter to fear, consistent with that prejudice, that their own practices are more risky:

“So when I also hear that HIV was common I didn’t know in which way it can come in my life. Already I was polygamist, you don’t know how one has protection. Did you think that you could be infected by sex? I was in a polygamist relationship.” E1

“Yes I fear HIV…You know from that time when I hear... I hear that people got it through sexual I got that sexual I’m just living like my father…” E39

That more traditional segment of the population would be more inclined to feel vulnerable when entering marriage. Their desire for children or difficulty using condoms in their marriage then makes protection more complicated. Marriage – which may not have the same spiritual value for them – may be more frequently associated with a sense of risk. Hence traditionalists would not necessarily consider marriage protective – quite the opposite, in some cases:

“A woman has secret sin in her heart she will not tell you everything she has in her mind and she will not tell you she made love with someone (…) You know when you have not married you know what is all about you, you are sure of the movements, but when you are in a group you cannot be assured of yourself.” E1

Yet the Christians did not report significantly fewer affairs or less premarital sex; their conversion sometimes happened after having been sexually competitive in their youth. In some cases, their sense of vulnerability with regard to premarital sex seemed hidden, if not completely, at least in what was said.

C. SENSE OF BEING PROTECTED FROM HIV

Most of the men that did not feel threatened by HIV had a strong Christian influence. Getting married was a form of protection that would continue into the future. Some who had not been taught this early and/or had not practiced total abstinence before marriage believed they could get married specifically for its protective value, as we said before:

“I thought when I married that I could not get infected because it would also stopping from having other issues out of marriage. I will depend on my wife.” E3

Some saw marriage as a form of protection because (in their view) having sex with only one partner was less risky, and also because its spiritual association made it protective:

“I didn’t stop walking here and there not because of HIV but because Christ came into my mind, in my life and changed my life… That has helped me. And saved me.“ E29

“It was hard but you know, if the heart has no God in it, there is no protection.” E38

Some thought that faith protected them, though their knowledge prompted some to get tested before engaging in marital sex:

“When I was at school I knew that HIV is contracted through sexual intercourse, it was my wish that God takes care of me that I get a wife who is not infected.” E35

To this man, his wife’s faithfulness was proven (among other things) by their not contracting an HIV infection over time. Condom use, recommended by doctors, made no sense because condoms were justified only in case of confirmed HIV infection:

“If my wife was not faithful to me we could get HIV and AIDS… so when I use my own wife without condom I don’t see any problems (…) If you are walking here and there we could have got it and we could have been using condoms by now. “ E29

Some associated condoms with infidelity and risk:

“My wife, I don’t use condoms... Because she will think you don’t love her (…) If you use condoms, she may think you have other sex partners.” E15

Sometimes, prevention involved observing their partners; this was primarily about symptoms, and about how much they trusted each other. Their judgment regarding the absence of risk – or lower risk – was based on that.

“I had to discuss about it before we go into act we discuss about it. Even testing was not there by then so we discuss and if we trust...” E2

The Christian-influenced sub-population was more likely to see risk as connected to prostitution, unmarried women, and certain socioprofessional categories, and to consider their own practices protective. The more traditional men who did not feel themselves at risk tended to have little knowledge about HIV in general, and to have become aware of it late – at diagnosis, in particular.

VI. REPRESENTATIONS OF TESTING AND TESTING PRACTICES

A. REPRESENTATIONS OF TESTING

1) Testing, marriage, and fatherhood

Awareness of HIV brought with it a change in viewpoint regarding marriage and fatherhood. For many, marriage was often a form of protection by itself. Yet some rejected it due to HIV – on one hand, because marriage could be a source of transmission, and on the other, because marriage would force them to have a test that they were not ready to accept.

“At times I feared to get married (…) I was afraid by then and did not have courage (…) I had to take the girl to VCT first so that we may know our status before we get married (…) That also put you power to make money to your drugs (…) You had to at least look for money to treat the sick so by the time the person dies and you, you are left poor for that fear made me at least not to get married. “ E37

As they saw it, the combination of marriage and HIV infection would be too heavy a financial and health care burden. These men claimed that if they turned out to be HIV-positive, they would be unable to both provide for their own care and that of their loved ones and fulfill their familial responsibilities:

“And I really feared to be HIV positive because it will prevent me from having children and getting married (…) if you are affected by HIV it is just a new lifestyle or if you don’t adhere to the rules on the recommendation of the new lifestyle. That is why I am saying the one who win the competitions is either poor or dead.” E37

So the first step was to be tested themselves so that they could get married, and then take preventive measures after that. The condition for getting married was that their future wife would agree to be tested. This man also expressed a fear of having his partner refuse to be tested and of difficulties discussing HIV as a couple before marriage, which might lead to a refusal to get married:

“To find a girl very courageous enough to let us go to VCT, to HIV testing and counselling it was very, very much hard.” E37

Some felt it was easier for married people to get tested because being positive would have fewer consequences for the couple once they were married. Knowing that their spouses would have to be tested when hospitalized for maternity care would make it easier for the men to agree to be tested:

“The unmarried ones those who are not married they fear testing but those who are married they don’t refuse. Because nowadays if a woman goes to the hospital she is supposed to be tested positive or negative so they know (…) They think also that if you have a virus you’re not supposed to marry so that is why they fear.” E41

Some felt that getting tested beforehand might lead the woman to refuse to get married:

“With the ladies if you say that before you get married “let us go and get tested” she might run away.” E41

If their wife or child was HIV-positive, some automatically assumed they were also positive. After that, they did not see any need to get tested:

“I could also accept myself to be sick because if the child was born sick, so all of us are sick. That is why I did not ask for a test.” E27

With regard to fatherhood, HIV often represented a threat, insofar as an HIV diagnosis would make it morally impossible for these men to have children, due to the risk of infecting their wife and progeny:

“Yes, they delay testing because it will prevent them from having children. They are being told by misconceptions that “I am going to pregnant the woman, the woman is going to give birth to a child so it is better I stay alone with my HIV. I was born a man, I’ll die a man” E41

Others seemed to set aside this risk, and the importance of fatherhood seemed to outweigh the threat represented by HIV.

“What I know is my child is sick, even right now the child is under drugs, our life is still…hmmm… every human being wish to have a child.” E27

There seem to be two types of testing-related behaviors guiding the view of marriage and fatherhood.

Some men prioritized marriage and fatherhood over testing:

• Either because they felt they had previously taken risks and testing – if positive¬ – might rule out marriage and fatherhood. There would indeed be a risk of transmission, or an inability to meet the inherent responsibilities of being the mainstay of the family. So testing does not happen.

• Or because marriage represented protection at a given time t – despite some feeling that they had previously taken risks. Some stopped considering risk once they were married, and freely experienced fatherhood.

Others felt that marriage and fatherhood depended on the HIV risk. Due to the need to protect their future spouse and children, marriage might be impossible without being tested beforehand. Some of those men avoided, or at least delayed, marriage. Others, who seemed better informed about HIV, did marry and begin having marital sex, provided both members of the couple knew their HIV status.

2) Factors that limited testing

Some men did not view testing as a way to protect themselves from HIV, or consider it a way to get access to treatment. Getting tested was not a way to improve their quality of life, but a source of additional constraints. Treatment led to greater acceptance of testing, since diagnosis led to treatment that helped stabilize the disease. Thus testing took on new meaning, and diagnosis meant hope of longer survival. Not everyone knew about treatment, however, and some still associated testing with impending death:

“Because people were saying “I’d better die without knowing my status than knowing that I am HIV and living with it, I will die faster”. This is a belief. They believe that after knowing that you got it, you have chance to die very fast but you don’t know you can stay with it.” E30

Those men felt it was better to live without knowing they were HIV-positive than to agree to a test that was synonymous with near-term death. This denial was not necessarily accompanied by a feeling of vulnerability or fear of the stigmatization that might result from disclosure of their HIV-positive status. Nevertheless, such motives seem to be an important cause of test refusal. It also seemed that test refusal was often due to the assumed impact of being HIV-positive and of treatment on their self-image, their bodies, their capacities, and their future plans.

“No I said it is a better that remain a secret to me (...) From today I changed, that is why I accepted the test today, because she told me if we find the virus by now when I am still strong, no one will realize that I have the virus so I will just continue with my activities, working, doing everything and I will be the one to decide where I will be taking the drugs. Just from there I decided to change my mind.” E28

The fact that the drugs only keep the disease in check and must be taken for life also seemed to be limiting factors in terms of testing:

“The people refuse, they know there is drugs to nurse it but not to treat it. We have been told that these ARVs they are boosting immune system they are not treating.” E41

3) Testing and reputation

“There is a day they came where we worked (…) everybody had a test, it is only me who remained, so I feel embarrassed, if I refuse, I will be the only one who refused for the test. So let me just test myself. From a group of people doing something and then you refuse, of course the members will say there is something… They will maybe suspect that I am infected so I just accepted and maybe I found myself forced” E28

For this man, accepting the test was a multi-stage process. First, there was social pressure from his family circle and his village. Refusing to be tested in the presence of others in a public place, for example, might indeed make it look like he wanted to hide his HIV status or high-risk behavior. Under those conditions he agreed to be tested, though reluctantly. After that, he took the step of voluntarily going to a health care facility to ask for a test, something that same circle might associate with risk-taking, and thus be highly suspicious that he was HIV positive, causing inevitable stigmatization:

“Not afraid of having symptoms (…) now I would know I have it… but not going to the hospital and somewhere to be tested, or coming here for test me. I don’t want people to say “he has HIV AIDS, he has been affected” E28

Indeed, being HIV-positive can jeopardize a man’s social status and status as the mainstay of the family, and his ability to fulfil his responsibilities and personal plans – due not to the disease itself, but to the image of the treatment, which leaves the man open to the judgment of those around him. Moreover, treatment comes with a lot of constraints. This rejection, combined with denial about a potentially positive result, led some men to wait until they had symptoms to begin care:

“No even the community, because when you are using the drugs, they will just find the truth (…) From there I’ll be sick, then I’ll decide what to do (…) I was afraid of taking medicine every day. I did not think of taking the drugs, I thought if I find myself with drugs, I will kill myself.” E28

Test refusal or acceptance was based neither on the sense of risk, strong or weak, nor on the direct consequences of potential disease, but on the social (and, to a lesser extent, professional) consequences of being HIV-positive and taking the drugs. For interviewee E28, it took the assurance that he would be fully able to meet his responsibilities (since starting treatment early would prevent any symptoms) and the possibility of getting anonymous follow-up care far from where he lived, to persuade him to have the test.

There was already prejudice stigmatizing certain occupations. For some men, that stigma created misgivings about being tested, or strategies for getting tested without risk by finding a place to get tested far from home or work, since their income depended on their reputation:

“They say that motorbikers are at risk to get infected by HIV (…) Some are afraid, some go for testing at night or very far away from here (…) Because when you are a motorbike rider, a lot of people know you and they meet a lot of people. That is why they don’t want to be tested.” E22

4) Trivialization of HIV

HIV is sometimes seen as a commonplace disease, like other STIs or other diseases in the region, like malaria. Some even saw it as secondary:

“But now community don’t perceive it as a killer because there is some drugs that you may swallow. So it is something taken under control, so this time we normally talk of other killers like cancer or malaria (…) People don’t fear it more or so because stigmatization is down.” E2

In some cases, the fact that there was a treatment for a condition that people knew to be silent – but did not know was deadly – made testing easier:

“I did not know my life was at risk… I did not know that my life was at risk, but I wanted to know my conditions, to see if I can start drug…” E9

5) Questioning the risk and testing

Sometimes, the medical community’s prevention message was misinterpreted or transmitted incorrectly. That message was used to minimize the men’s feeling of vulnerability. First, a lack of symptoms was interpreted as an absence of infection – a feeling reinforced by the medically-confirmed existence of serodiscordant couples. Second, an absence of genital lesions was thought to make HIV transmission impossible. So care was delayed significantly – until symptoms appeared and enough external pressure was applied.

This man denied needing testing, despite the fact that his partner was HIV positive. As a priest for his church, his reputation would be jeopardized by a positive test; he seemed to be going through a process of self-negotiation and weighing the risk:

“There is a teaching that you can find that one partner is positive and the other partner is negative. So I thought I was negative and she was positive… Yes, and even sometimes they say there was false results, that there is machine that could not detect the virus. That is why I did not have a test, because I did not have any symptoms, and I feared the test (…) We have been educated that you can have sex but if there is no wounds on your private part no cut so there is no entry point for HIV/AIDS so that is a possibility to come off it” E38

6) Testing as a personal action. Female influence.

What women said had varying degrees of influence on whether the men were tested. In general, women played a significant role in their loved ones being tested. Their approach was either direct or indirect. There was either a confrontation with direct urging to get tested, or more indirect strategies aimed at avoiding confrontation:

“She is the one who, silently, suspected that I was infected. Later, my sister was in Nairobi and my sister advised me, well she invited me to visit her at Nairobi so I was going to visit my sister but it is like, some arrangement had been made for me to see a counsellor so she did this by my knowledge” E7

For the men who experienced it, that urging came mostly from female family members like sisters or mothers. Yet female influence regarding HIV was rare. Indeed, some men refused to be tested despite the possibility of openly discussing the risk with their partners and pressure from close family members. To this man, disease, and thus risk, was associated with symptoms. He did not care what his family thought of his levirate marriage and the attendant risk. Although he had respected the opinion of the village elders his entire life (for his marital choices in particular), he felt that HIV was a personal matter:

“My wife was no satisfied, she said after I’ve gone there, the people come to her and told her “you know this thing, from what that person died” (…) You know this AIDS, they have taken it as essential (...) It is not a community affair, because you are not for me, I am not for you” E18

The younger men were more likely to consider testing a personal undertaking. Some got tested even without symptoms. Their first test – not requested but offered during government or NGO interventions – usually fell into this category. Pressure from loved ones was a far less important factor.

Among the older men, choosing to be tested was less of an individual decision; it was due to pressure from mainly female loved ones and to the death of loved ones. In addition, those men tended to draw a connection between the onset of symptoms and the possibility of HIV infection, while the younger men often attributed their symptoms to other conditions, such as malaria – a more common, more disabling, and equally deadly disease, especially in the short term.

B. TRIGGER FOR THE FIRST TEST

1) Exposure to the disease

Though sudden awareness of HIV due to contact with the epidemic’s effects came as a shock to some men, it did nothing to give them practical information about HIV and or raise some men’s awareness of testing. The possibility of testing positive was terrifying, and they refused to be tested. This was different, however, from denial or a lack of awareness of the risk that HIV represented. In the same sense, it did not mean that they did not take preventive measures:

“You could not go for test even to go to VCT or a lab you could not approach that place because HIV was a terrible disease (…) it is God who helped me around that time until I went for the testing (…) I was afraid to have any other sexual intercourse and partners and that is why in my life even now I don’t have any other partner. So I don’t get HIV. ” E3

2) Onset of symptoms

Few men said they drew a connection between what they already knew about the signs of the disease and their symptoms. Once obvious, the symptoms gave some men the idea that they might be HIV-positive and motivated them to get tested. More often, they connected their symptoms not to the possibility of being HIV-positive, but to other diseases like malaria, for example. Sometimes putting it off for months or years, they were eventually motivated to get tested (in the course of routine care) by the frequent reappearance of relatively banal but bothersome symptoms. The possibility of HIV infection had not occurred to them before their hospital visit or test; all of these men were traditionalists:

“Bodies had been brought from Mombasa, who died from HIV AIDS (…) I didn’t know because when the dead body came, they were wrapped, so we were told this is a disease that killed the man (…) I thought it was like any disease, like malaria, headache, like any other disease (…) One of my friend go to those white men and said to me “they treat the disease”. That is how I came to them.” E43

Many people associated the symptoms and treatment behavior with beliefs from systems other than modern medicine, for example:

• Traditional beliefs associated with Chira, a curse on individuals who fail to respect the rules of Luo society. This caused people to blame their symptoms on current or past behaviors that they sometimes deemed morally reprehensible. This also explains why they sought folk remedies, which further delayed the use of hospital services. The failure of traditional measures prompted some to get an HIV test, often due to pressure from their loved ones, thanks to the visibility of testing campaigns:

“During that time before I was tested, I thought it was the cause of my sickness, it could be Chira but after I was tested I knew the problem, I know that one is now useless, it is not the cause of the problem, but HIV AIDS. Even if he works on the piece of land, I don’t care. Did you know that HIV existed when you fell sick? Yes. Did you think it could be HIV? My mind did not think of that, because my mind was set on cultural beliefs.” E8

• Christian beliefs, which prompted some patients (one example being the members of certain religious movements like Legio Maria) to rely exclusively on prayer for treatment.

“I pray before I go to the hospital then when it is becoming difficult for me, I go to the hospital. So I pray trying to get healed and if it fails I go to the hospital.” E35

C. IMPACT OF THE FIRST TEST ON PRACTICES

1) New sense of risk

Testing was the moment at which some men first sensed they were at risk. Not because they were engaging in what they considered risky behaviors, but because of the ubiquity of the HIV epidemic, transmitted easily by routes other than sex. Those men tended to question some of the old values – for example, the view among some Christians that marriage was protective. Indeed, couples were urged to get tested together, and barrier protection was recommended for sex within marriage:

“I think she could infect me. You know those who are teaching us about HIV thus people teach us that you can get HIV not only through sexual but sharp object: razor blade, knife...” E39

2) Impact on marital and extramarital sex

Testing is an opportunity for medical institutions to deliver a message to HIV-negative patients on modifying their sexual practices. Married men were advised to stop having extramarital relationships and to use barrier protection with their wives:

“They told me that my status was very good and that I had not to have sexual intercourse with other lady (…) They told me to take care of myself to use protection because we were negative.” E35

Doctors advised some unmarried men to stop having sex before marriage. In other cases, medical professionals recommended condom use and circumcision when men were tested:

“So there was those who visit door to door and they were teaching that men must go to circumcision to reduce the rate of infection. I know it is a disease, and it kills (…) we use condoms. Men must also be circumcised to reduce the infection.” E21

The recommendations on sex dispensed to single, HIV-negative men during testing often had little, or only partial, effect – either because they were inappropriate, as mentioned previously, or more often because they were already being followed prior to testing, after the men had become aware of HIV. The recommendations that did seem to have an effect were primarily those regarding barrier protection within marriage. Yet the extent to which this recommendation was followed varied depending, in particular, on the perceived risk, the existing sense of protection in the marriage, and religious convictions. It seemed to be the most religious men that most questioned condom use after these recommendations. The others weighed condom use against their desire for children and their ability to negotiate condoms with their partners. We also saw the importance of marriage, in particular through its association with having children. Yet the medical community urged the married men we questioned to use barrier protection with their own wives, even when both members of the couple were HIV-negative:

“They told me that my wife and myself were two different persons maybe one may have other relationship and then the other one do not know. So I should use condoms (…) I was surprised first, then later I realized it was a good thing that could help me. So that I may continue living (…) They told me that any of us maybe is not faithful to the other and that if we don’t use condom it may have real effects on us.” E3

This is where one sees the bind these men found themselves in, feeling obliged to follow medical recommendations on condom use. Since having children was sometimes their first priority, condom use was only partial:

“When I enjoyed sex as a leisure I use condoms, but if it is for procreation, I have to use it free (…) When she has attended her monthly period, and then the monthly period end, I should use free flesh without condom to make her pregnant. (…) From that time we did not have another child. We still have faith God to give us a child.” E33

3) Repeat testing

The men were advised to get re-tested every three months, regardless of the social or professional context, their view of the risk, or their practices. Many tended to follow that recommendation, even when they saw no risk. The medical community justifies that approach by the fact that there are other transmission routes, aside from individual practices deemed to be high risk. Hence there was always a feeling that infection was possible, despite behavior changes and a negative HIV test.

“No, I did not feel at risk but later I understood that it can really get to anybody even if you don’t have sexual intercourse (…) They told us there is HIV and AIDS and the ways people can contract it”. E29

As pointed out earlier, these men had to go through a process of reflection and of analyzing their risk, their past practices, their sense of vulnerability, and the potential consequences of the test before agreeing to be tested. Even learning that they were HIV-negative had consequences, in terms of taking preventive measures, needing to repeat the test, or developing a sense of risk, leading to changes in their social relationships, for example:

“After testing, if I found I am ok, I have to take care of myself. I need not to have many ladies, (…) After playing I went to my room booked for me only to sleep. When we have to come back, I come back. I have only one lady. When she is not there I cannot meet any lady even if I have to stay there for 5 to 6 month, I can just stay.” E13

VII. IMPACT OF TESTING POSITIVE

A. BEING INFORMED OF THE DIAGNOSIS - IMMEDIATE REACTION

1) Sense of imminent death

For some of the men, learning that they were HIV-positive was a shock, as the diagnosis was synonymous to them with imminent death. As indicated with regard to representations of the test, this was due to the idea that once diagnosed, HIV was almost immediately fatal:

“I almost lost hope in life, I was just counting my days. I knew my days was numbered, I was waiting for that time (…) at that time, we knew that once you are found with the virus, the final to handle will be death. So that thing really stressed me” E7

The feeling of imminent death was experienced by men of all ages and socioprofessional backgrounds, all of whom were diagnosed after antiretroviral drugs became available in the area. In some cases, the feeling was observed even in men who were more knowledgeable about HIV and its treatment. For many, the anxiety was due to personal experiences or beliefs, and to the fear of dying or being stigmatized. However, it also seemed related to a sense of responsibility to their family, which could face great difficulty after their death:

“We think we may die and leave our children without anyone to care for.” E34

2) Unexpected diagnosis

Some men were shocked when informed of their diagnosis. They had assumed they were protected against HIV, hence their surprise at being diagnosed HIV-positive when nothing in the past would have suggested it – they had not taken any risks or had any symptoms that could be attributed to HIV. For the men questioned, the shock seemed to be significantly mitigated by the fact that there was a treatment, and by medical community messaging:

“When I was at the hospital, the first day I got little worried and then they put me on the drugs but still I kept on going but as I went on taking my drugs, I now got a lot of courage.” E16

For others, the diagnosis was unexpected but not necessarily surprising. While their practices did not lead them to suspect HIV infection, their proximity to and knowledge about the disease helped them accept it more easily. Those men, who did not expect their diagnosis, were relatively young and often married at the time of diagnosis:

“I did not feel really sick. I was just normal because I was counselled and I am also a counsellor, I know how to handle these matters, I was just relaxed, I am not the only person who is supposed to be ill, many people are positive so the life continues” E25

3) Seeing testing and diagnosis as means of recovery

Some of the men thought that they were about to die just before testing positive. Because their symptoms had been very obvious and unresponsive to the treatments tried to that point, the HIV test – often fortuitous – made a recovery they no longer expected possible.