Xavier Plaisancie

Doctor, graduate in tropical medicine. He began working with MSF in 2016 on issues related to access to HIV care for men in the Homa Bay district of Kenya under the supervision of Jean-Hervé Bradol and Marc Le Pape. This research will form part of his medical thesis, which will be published in a CRASH book. Then, in 2019, he joined the oncology project in Bamako, Mali, as a palliative care doctor and researcher on the trajectories of breast and cervical cancer patients. He worked with MSF in Kinshasa as a doctor in a ward caring for patients living with HIV at the AIDS stage. Since 2022, he has been pursuing a master's degree in the sociology of health at EHESS which, in conjunction with CRASH, has led him to take an interest in palliative care practices in Malawi and the development of the discipline in a humanitarian context.

Chapter 1 - Framework of the study

I. DEMOGRAPHIC DATA

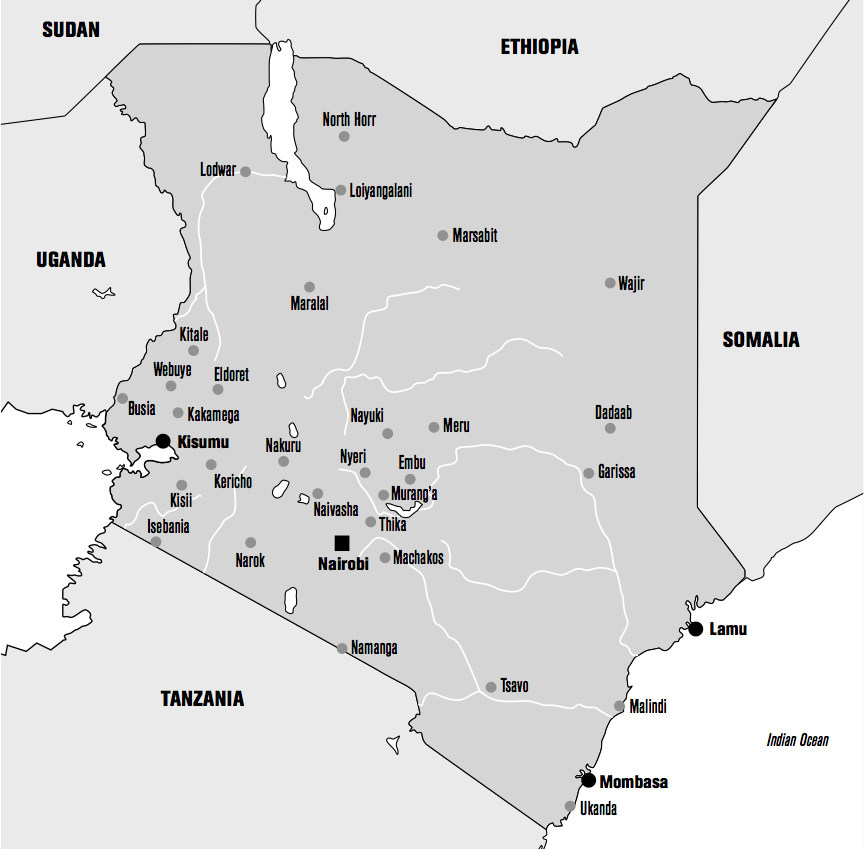

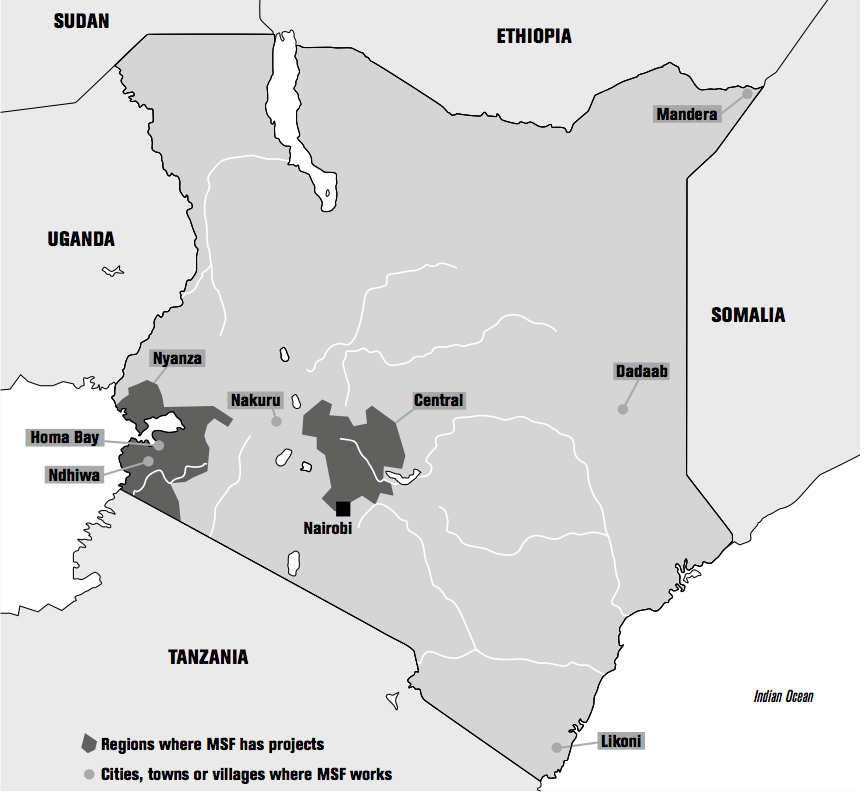

Nyanza Province, which encompasses Homa Bay County, in particular, is inhabited primarily by the Luo people, the country’s fourth largest ethnic group. In total, this ethnic group represents about 3,000,000 people in Kenya, or 10% of the country’s population. Though the Luo live mainly in Nyanza Province, they have always been present in the large urban areas as well (39) (55).

Nyanza Province is located in southwestern Kenya, on the shores of Lake Victoria. It is divided into two parts, South and North. Kenya presently has 47 counties, which are themselves divided into districts. The former Nyanza Province includes Homa Bay County, which in turn contains the sub-countie of Mbita, Ndhiwa, Homa Bay Town, Rangwe, Karachuonyo, Kabondo, Kasipul and Suba ; this has been the case since power was decentralized when the new constitution was adopted in 2010 (45).

The population of Homa Bay County was 462,000 males and 501,000 females in 2009, and 542,000 males and 584,000 females in 2016, corresponding to 206,000 households in all (56).

II. CURRENT PUBLIC HEALTH SITUATION

Here we report the studies done by MSF in the course of caring for patients at the Homa Bay hospital and working in Ndhiwa district. While the results presented are not perfectly representative of Nyanza Province as a whole, they offer a glimpse of the health situation that MSF faces.

A. CURRENT EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SITUATION

1) Homa Bay Hospital

The overall mortality rate at the Homa Bay Hospital in 2015 was approximately 16%, all pathologies combined. The HIV prevalence among the hospital’s inpatients was 49%. The mortality rate for those patients was 16%. Eighty-four percent of HIV-positive patients had been diagnosed prior to admission. Of those HIV-positive patients, 63% were on triple therapy. Seventy-four percent of the patients had been hospitalized at the treatment failure stage. Nearly all of the patients in treatment failure were still on a first-line treatment regimen.

In 2016, the mortality rate was higher for HIV-positive men than for HIV-positive women. The overall mortality rate at the hospital was 14.4%; 37% of those deaths occurred in the first 24 hours. The mortality rate for HIV-positive inpatients was 19%; 26% of those who died did so in the first 24 hours (62). A study on the reasons for admission and mortality at Homa Bay Hospital showed that men came in for care at a more advanced stage of the disease and that the mortality rate was higher for men (19%) than for women (8.8%). Men continued to have a higher mortality rate after discharge (cumulative mortality rate of 40.7%, versus 25.9% for women) (53).

2) Ndhiwa District

The district has four main working dispensaries, in addition to the Ndhiwa Hospital. In 2015, the district’s estimated total population was 242,726, of which 47.6% were male and 52.4% female (62).

Epicentre’s Ndhiwa HIV Impact in Population Survey (NHIPS), conducted in collaboration with the Kenyan authorities and MSF in 2012 (6), showed an HIV prevalence for ages 15-59 years of 24.1% and a mean incidence rate of 2.2 new cases per 100 persons per year. In that age group, 13,250 people were diagnosed with HIV.

The estimated number of PLHIV in Ndhiwa District in 2015 was 22,037 (62). Hence, only 60% of HIV-positive patients were being followed. The share of patients on antiretroviral therapy was 50%. In Ndhiwa Hospital, 63,146 people were tested in 2015; 4.69% of them were HIV-positive. In 2015, 2,962 people were diagnosed as HIV-positive. Of those 2,962 people, 82% were integrated into the health care system.

During community-based testing, which began in April 2015, 7,312 people were tested and 3.24% tested positive.

Were there differences between men and women? Men were tested as often as women, except in the health centers where women were tested more often. The positivity rate for tests done in 2015 was 2.39% for males and 4.12% for females.

B. CURRENT TESTING CAMPAIGNS

Testing strategies have changed over the years (53), evolving from voluntary at the start of MSF’s intervention to care teams offering testing in dispensaries or hospitals. MSF later organized community-based testing campaigns, and finally home-based testing using a “door-to-door” approach (62). The latter approach, chosen to reach the most isolated rural populations, is part of what is known as COMMOB (community mobile-testing). This activity began in April 2015 and works as follows. A location is chosen. A base camp is set up for assembling the testing equipment and teams. There are nine people on each team. Each team has a leader who coordinates the activities. The rest of the team consists of six counselors, a lab tech responsible for measuring the CD4 count if someone tests positive, and a counselor who specializes in managing HIV-positive patients, to arrange for their subsequent treatment.

Each team is taken to an intervention area. Each counselor, equipped with testing equipment, then goes off to test families who have not yet been tested. Each house tested is marked to prevent another counselor from going there. A local liaison introduces the counselors to the families to make the testing process more acceptable. After the residents are given advice and information on HIV, the testing begins. If the test is positive, the lab tech is called in to take blood, in order to confirm the diagnosis and measure the viral load. The patient is then asked to come to the hospital or a dispensary for treatment. If the test is negative, prevention advice is given. Everyone living in the house is tested. Couples are tested at the same time, and the prevention talk is given simultaneously to both members of the couple, if possible. Children over age 15 years are tested. Confidentiality is not always respected.

MSF has done 10-13% of the home-based testing in Ndiwa District (other organizations also conduct this type of intervention). Once all of the houses are visited and tested (or not), the COMMOB moves on to another locality to carry out the same testing effort. Testing is also done via “moonlight consultation” sessions. These sessions allow men who are unable get away during the day to go to a conventional facility – or be home for door-to-door testing – to get tested. The sessions are held once a week, and vary depending on the possibilities, availabilities, and dissemination of information about them in the population. The moonlight location changes once a certain number of people have been tested. The tent is set up at the end of the day. Several counselors take their places in the partitioned tent to do the screening tests, which go on until midnight. The final portion of the testing is done in the outlying clinics.

C. FOLLOW-UP CARE

HIV-positive patients are followed at several different facilities (53) (62). Some are followed at Homa Bay Hospital’s Clinic B. Others are followed at “hubs” (the main dispensaries) or at the outlying dispensaries. The choice of follow-up facility is theoretically left to the patient. These dispensaries are run by the MoH with MSF support.

In terms of materials, MSF supplies the third-line antiretrovirals and Kaposi’s sarcoma treatment. In terms of human resources, two teams run the dispensaries. Each team consists of an adherence counselor, a Kenyan doctor, a team leader, and a psychologist. These teams go to the main dispensaries each week and to the other dispensaries once a month to collect the data in order to evaluate the dispensary’s activity, discuss difficult cases, and make treatment decisions regarding those complicated cases. Sometimes the cases are referred to other teams or to Homa Bay.

If poor adherence is suspected, the treatment is not changed immediately but a visit is scheduled with the adherence counselor. If the viral load is too high after verifying good adherence, secondline treatment is started.

According to Kenya’s national recommendations, the viral load should be measured after the first six months of treatment, and then every year. Any viral load >1000 copies/ml is suspicious for treatment failure, and requires a change in the treatment regimen. Currently, viral load testing is done at only one laboratory, in Kisumu, far from Ndhiwa. Once a sample is taken, it takes 1 to 3 months to get the results back. Some results are delayed, or never arrive at all.

Compliant, stable patients on antiretrovirals are seen every six months, though the drugs are dispensed every three months. Patients who show signs of a relapse are seen back sooner, generally in two weeks to a month, then 3 months, and then again 3 months later with a new viral load measurement.

Période

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed about our latest publications. Interested in a specific author or thematic? Subscribe to our email alerts.