Humanitarian Field Practices in the Context of the Syrian Conflict from 2011 to 2018

Hakim Khaldi

This article was first published in Issue 2, Volume 2 of The Journal of Humanitarian Affairs.

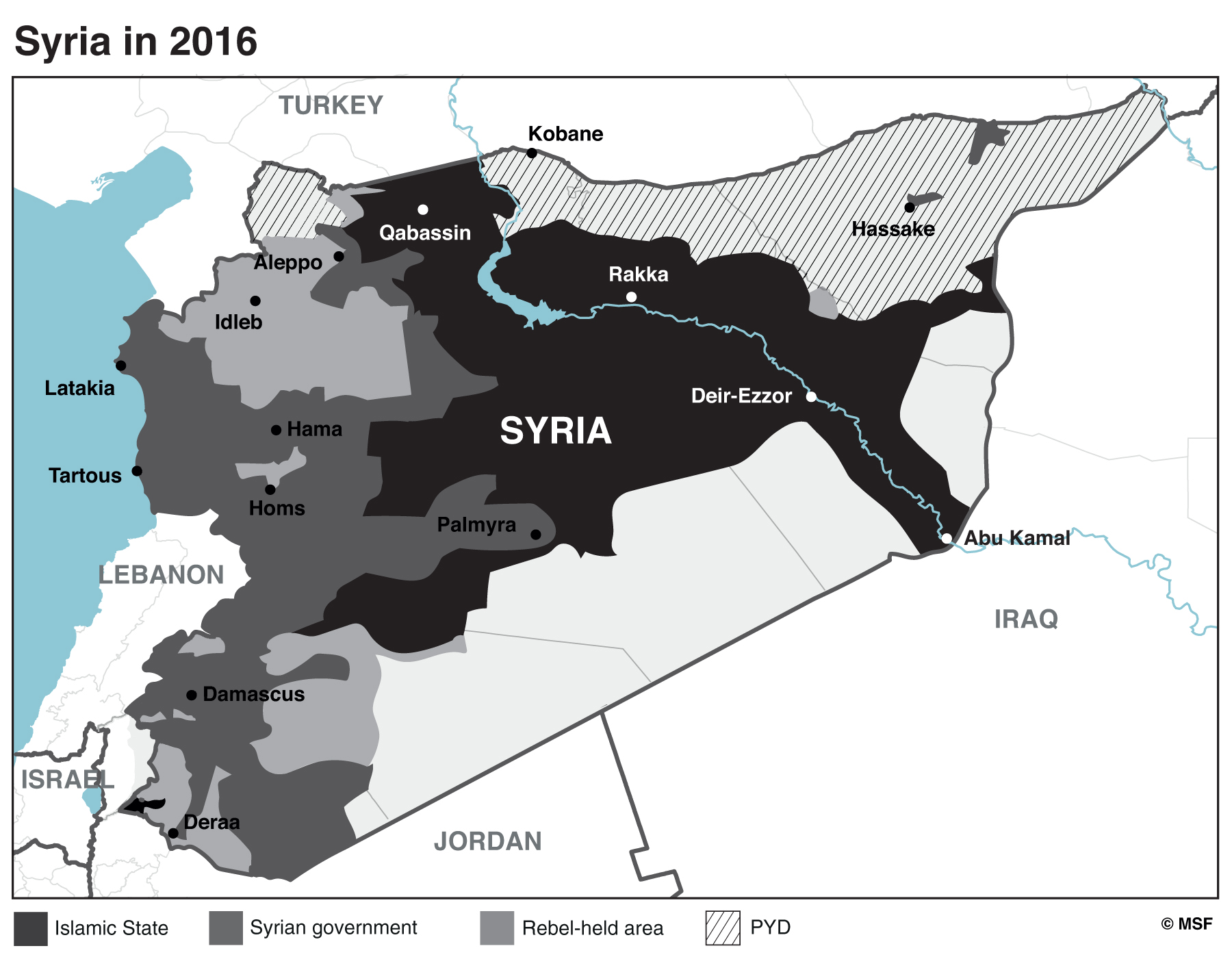

How can a medical humanitarian organisation deliver emergency assistance in Syria when there is nowhere in the country where civilians, the wounded and their families, medical personnel and aid workers are not targeted? Not in the areas controlled by the government, nor in those held by the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) or the different rebel groups. So what action could be taken, and how? Remotely or on site? At the very least, we had to decipher the diverging political and military agendas, and then adapt, persist or sometimes just give up. In this article, I will present the full range of methods used to acquire knowledge and obtain information as well as the various networks used to carry out this venture. I will also show how Médecins Sans Frontières’ operations became a balancing act, punctuated by episodes of adapting to the various difficulties encountered.

My analysis draws on a range of surveys and documentation.Hakim Khaldi is an Arabic speaker who works in MSF’s Operations Department in Paris where his job is to monitor and analyse transnational armed conflicts. To this end, Khaldi takes part in negotiations and operations in the field in the Middle East to which he made many visits between 2012 and 2019. I carried out fieldwork on missions conducted between 2012 and 2018 in the towns of Ain Issa, Aleppo, Al-Bab, Atmeh, Kobani, Manbij, Raqqa and Tabqa in the north of Syria. I also had access to Médecins Sans Frontières’ (MSF) archives in Paris (preparatory documents for reports and speeches as well as emails, press releases and official correspondence). And over this same period, I monitored the postings of journalists, activists, analysts and armed groups on the internet. I also carried out qualitative research through interviews with different protagonists: in the north-west, with members of the Union of Medical Care and Relief Organizations (UOSSM)A French and international NGO created in May 2011 as a result of the determination of Syrian and international doctors to respond to the health emergency in Syria. – including one of the founders – and with MSF’s Head of Emergencies in Paris when the first relief operations were put in place in 2011 and 2012, as well as with the different MSF coordinators in charge of projects in the north-west and north-east and in Qabassin – under ISIL control at the time. I cross-referenced my analyses with those of other researchers and journalists covering the Syrian conflict.

My aim in this article is to describe the operations conducted by MSF France in four distinct areas of Syria from 2011 to 2018 during the country’s civil war: the governorates of Idlib and Aleppo, controlled by different rebel groups; the north-east, administered by the Syrian branch of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), under the protection of the US army; the town of Qabassin during ISIL’s rise to power and, lastly, the government-controlled areas around Damascus. This account relates MSF’s work in each of these four areas. Occasional references are made to other MSF operational centres (Belgium, Spain, Holland and Switzerland), which carried out independent relief operations, while endeavouring to coordinate their actions as much as possible.

From Damascus to the Rebel-Held North-West

In June 2011, as the Syrian government violently suppressed demonstrations by its opponents, MSF France attempted to negotiate permission to work out of Damascus. But meeting with the authorities proved impossible. The Syrian intelligence services had closed the offices of MSF’s Spanish section a few weeks previously, accusing it of supporting the ‘revolution’.

With all the official channels closed, MSF went through a foreign journalist to make contact with the president of a local Syrian non-governmental organisation (NGO) that was providing assistance to Iraqi refugees. This NGO, which cannot be named here as it is still operating in Damascus, was part of a network supporting both official medical establishments (like Shifa Hospital in Hama) and clandestine facilities via the tansikiyats (coordination committees – new institutions created by Syrian citizens in 2011) (Burgat and Paoli, 2013: 90). In December 2011, the Syrian president of this NGO and its administrator (a French national) met with MSF’s Head of Emergencies in Paris. This administrator was subsequently recruited to coordinate MSF’s project in Damascus, with technical and financial support from a team based in Beirut, Lebanon. From January to March 2012, despite the regime’s persecution of the wounded and any medical personnel caught caring for them (Médecins Sans Frontières, 2012), he supported the opposition’s medical network in Deraa, Hama, Homs and Ghouta. He was eventually evacuated to Lebanon by the French Embassy in Damascus when the French chancery was closed. That same year, MSF began donating medical kits to hospitals in the south of Syria via its office in Amman, Jordan.

At the end of 2011, an MSF team was sent to the town of Reyhanlı in Turkey, on the border with north-west Syria. This new initiative resulted from a meeting with members of UOSSM at MSF’s headquarters in Paris at which they had asked MSF to take part in an operation to be run out of Turkey. MSF decided to draw on the support of its network of doctors inside Syria, in the rebel-held areas of Idlib and Aleppo governorates.

The team had spent several months watching powerlessly from the Turkish side of the border as bombs were dropped on Syrian health facilities and civilians when MSF took the decision to launch cross-border relief operations in the form of direct emergency medical assistance. Working out of Reyhanlı, still in collaboration with UOSSM, MSF entered Syria in May 2012, arriving in the village of Atmeh in the north of Idlib governorate, situated just a few hundred metres from the border. In June 2012, a clandestine hospital was opened, with the help of a doctor who was also the local UOSSM manager. At this point, in order to protect its teams, MSF wrote to the Syrian government to inform it of its intervention (see page 10).

Exploratory Mission

On 19 July 2012, the different rebel groups launched a major offensive on the city of Aleppo in an attempt to seize the country’s second city before attacking the capital. This military engagement led MSF to question its geographical positioning in Atmeh, 80 km west of Aleppo. The violent fighting was causing many casualties and yet we were seeing no increase in the number of war-wounded at MSF’s hospital in Atmeh. So where were they being treated? By whom? How? It was decided to conduct an exploratory mission in August 2012 to identify the problems encountered by the population and medical facilities, as well as any solutions existing locally and potential for improvements. This required a context analysis. For the populations affected, it involved identifying their state of health, their needs and the resources to which they had access locally. For the medical facilities, it meant determining their needs for drugs, medical equipment, water and power, as well as their reception and patient management capacity.

Two members of MSF’s international personnel – including the author of this article – went to Aleppo in August 2012. We had already developed a relationship of trust with UOSSM’s medical coordinator. This coordinator, a doctor originally from Aleppo, was based in Reyhanlı where he was providing permanent medical and financial support to a network of activists supporting various facilities in rebel-held areas. It was thanks to the members of this network that we were able to gain access to Aleppo, as their knowledge of the city and organisation helped us avoid the checkpoints put in place by the army and Syrian intelligence services on our visits. They also enabled us to cross over from the government-controlled zone to the rebel-held zone. We met with the leaders of the network in the home of one of these activists in a government-controlled area of Aleppo. Although they initially refused us permission to visit the care sites they were supporting, after a brief negotiation, we were given the green light for the next day.

During this exploratory mission, we managed to visit the main care centres and determine their treatment capacity. We also established that the route for evacuating the injured didn’t lead west toward Idlib and our project in Atmeh, but east toward the city of Al-Bab. In Al-Bab, the two members of MSF met with the local council’s medical officer and obtained a relatively clear picture of needs. This doctor was subsequently recruited by MSF to work in the region of Idlib.

In the wake of this exploratory mission, it was decided to maintain the Atmeh project on the border (where thousands of displaced people would later seek refuge) rather than go deeper in-country, as this would increase the teams’ exposure to the different forms of violence generated by the war (airstrikes, mortar attacks, armed robberies, kidnapping, arrest, detentions, etc.).

New Projects

In the wake of the exploratory mission, two new projects were opened in September 2012: one in Kafr Ghan, in the north of Aleppo governorate, and the other in Al-Bab, to the east of Aleppo, where the seriously injured were being taken. The first of these projects, for managing the war-wounded, closed just a few weeks after it opened because of a disagreement between MSF and the local medical committee over the management of the hospital. The second was also discontinued due to repeated bombings of the city of Al-Bab and its hospitals by the Syrian army. MSF evacuated its teams from the city in January 2013. The Kafr Ghan episode also put an end to the collaboration between UOSSM and MSF, mainly due to a lack of confidence between their respective field teams.

In May 2013, a new project was launched in the town of Qabassin to the east of Aleppo. Its objective was to support a hospital managing war-wounded, other medical emergencies and the chronically ill in an area where the full spectrum of combatants were active: the Free Syrian Army (FSA), Jabhat Nosra (JAN), Ahrar Sham (AS), the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and ISIL. It is usual for MSF to negotiate with any armed groups present in the region in which it wants to operate, whatever their legal status, in order to gain access to the areas under their control and ensure the security of MSF’s operations. These armed groups benefit from the arrangement, obtaining health services for their own injured and for the civilian population in the areas they control. As for MSF, it provides medical care while seeking to ensure that its hospitals are recognised as ‘neutral zones’, i.e. weapons are prohibited and the site cannot be used for military purposes. In this particular negotiation, MSF sought to obtain three things: direct access to the target populations, permission to evaluate the needs of these populations freely and without constraint, and assurances that the aid provided would reach those initially identified as the recipients. In the case of Atmeh, the group controlling MSF’s intervention zone was AS, an exceptional group in Syria’s revolutionary landscape. Indeed, although AS was close to Al-Qaida in persuasion, this did not interfere with working relations and MSF’s ‘neutral zone’ was respected.

Atmeh – A Change of Direction

In 2013, camps were set up in Atmeh and all along the border with Turkey to provide shelter for thousands of displaced people fleeing the bombing. MSF set up mobile teams tasked with health and vaccine education not only in the camps, but also in the surrounding villages. The hospital focused on treating burns victims because of a growing number of injuries of this nature caused by bombs, artisanal refining processes and the use of poor-quality fuels. This change of direction was also due to a reduction in the number of war-wounded, itself due to the distance from the front line and the new surgical units set up by the armed opposition. At that time, Atmeh was a 17-bed hospital with an operating theatre (used for skin grafts), an emergency room, in-patient beds, a physiotherapy service and a psychological support unit. It was to become the only medical facility in rebel-held areas to be specialised in burns treatment.

Kidnapping: From Direct to Remote Management

On 2 January 2014, ISIL kidnapped five members of MSF Belgium’s team in Idlib governorate. MSF decided to withdraw all of its international teams working inside Syria (the Atmeh team was evacuated on 14 February 2014) and set up a system of remote management operating out of Gaziantep in Turkey, the nerve centre of the Syrian opposition and international aid. (By remote management, I mean that international staff no longer had access to the field and supervised their national staff colleagues from a distance.)

On many occasions, MSF considered sending international staff into Syria on flash visits (in and out in a day). But due to numerous incidents (intentional and repeated targeting of health facilities), the surge in ISIL’s activity (especially hostage-taking and assassination of foreigners) and the generalised insecurity (an increasing number of kidnappings of foreigners by different groups), the Turkish government withdrew authorisation for international staff to cross the border into Idlib.

The North-East under the Control of the PYD, Syrian Branch of the PKK

In 2012, military control of part of the border zone with Turkey was outsourced by Damascus to the Syrian branch of the PKK, created in 2003. This outsourcing was strategic: it displeased Turkey which was not only supporting the rebels, but saw the PKK as its long-standing enemy. Moreover, it allowed the Syrian government to concentrate its armed forces on other fronts. There were conditions attached to this understanding between the Syrian government and the local embodiment of the PKK (PYD/YPG). The PYD was not to provide any assistance to the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and was expected to neutralise any demonstrations hostile to Damascus (Baczko et al., 2016: 207).

There were two reasons for MSF France’s decision to launch an intervention in the north-east region in May 2017: the planned offensive by an international coalition against the region of Raqqa, controlled by Islamic State (IS) since 2014 and an appeal from representatives of RojavaIn Kurmanji, the principal Kurdish dialect spoken in Syria, Rojava designates the western area of north-east Syria. in Europe and France. This area was under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) is a military coalition formed on 10 October 2015. The dominant member is the YPG, the armed branch of the PYD. The SDF also include the rebels of the FSA and the militia of local tribes. The SDF are supported by the international coalition led by the United States. and the presence of the US army protected it from bombings by the regime. Furthermore, the Kurdish militia’s tight control over the population meant MSF’s international personnel were at no risk of being kidnapped. As a result, it was one of the rare areas in Syria to which it was possible to send international staff. Access was not controlled by central government but negotiated locally with the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) of Massoud Barzani on the Iraqi side and with the PYD partisans of Abdallah Öcalan on the Syrian side.

MSF France developed two main types of intervention here: co-management with the local health authorities of a hospital in Kobani treating people wounded during and after the offensive on Raqqa and the local population; management of health centres in the Ain Issa IDP (internally displaced persons) camps and also for the displaced people in the town of Tabqa. These activities were intended to fill the gaps in the local public health system. MSF Holland and MSF Switzerland had been working in the area since 2013. The interventions by the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was limited to a few IDP camps, as the Kurdish authorities preferred to work with the Kurdish Red Crescent (not recognised by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). Interventions by NGOs working out of Damascus and the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) also remained very limited in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) zone.

MSF’s main interlocutor for setting up and developing these projects was the Kobani Health Authority, a sort of regional health ministry. It is with this authority that we negotiated our different activities. More locally, in Ain Issa and in Tabqa (Raqqa governorate), we had to go through the towns’ civil council.

Each civil council was organised in the same way: headed by two people, a man and a woman, in charge of different committees (internal security, medical, ‘mill and oven’ for food management, NGOs, etc.). MSF always focused on developing relations with the medical committees.

In addition to the Kobani Health Authority and the civil councils, there was also a regional administration based in Ain Issa that reported to the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political branch of the SDF. Any international NGOs wanting to operate in the regions of Raqqa, Manbij and Deir Ezzor had to obtain a work permit (to be renewed every six months) from the SDC.

In theory, all of these administrations answered to a higher authority, baptised the Autonomous Administration (Idara Zatiya) by the PYD. However, my observations and experience enabled me to determine that all the important decisions were being taken by the local leaders based in Kobani, Ain Issa and Tabqa. These local leaders were themselves overseen by people known as ‘the men in the shadows’ – PKK executives.

The Offensive on Raqqa and the Fate of the Civilian Populations

The military offensive was launched by the SDF in June 2017 and backed up by the air forces of the anti-IS coalition. As the weeks went by, MSF’s hospital in Kobani saw very few of the wounded. Drawing on my experience of the offensive in Mosul, where I had led a similar project a few months previously, I described this situation in an opinion column published in August 2017:

During the month of June, Kobani hospital, managed by MSF, treated 64 people for war-related injuries. Most of these patients came from the areas surrounding Raqqa and not from the town itself, and their injuries were mainly caused by landmines (90%). With a few exceptions, we are not seeing the wounded from Raqqa. The contrast between the intensity of the bombing on a small area of the hermetically sealed town and the low number of injured being cared for by our teams conjures up the final phase of the battle of Mosul which the Iraqi Army has just recaptured. The comparison between Mosul and Raqqa has its limits because the environment and context are different. But, whereas in Mosul assistance for the displaced and medical facilities were rapidly put in place, in Raqqa they weren’t even considered. (Khaldi, 2017)

In its offensive against IS in Raqqa from 6 to 12 June 2017, the US-led coalition made no distinction between combatants and civilians, nor did it plan for the evacuation of civilians. On the other hand, IS combatants were safely evacuated back to their remaining strongholds in Syria.

Civilian populations who lived in the areas controlled by IS have suffered threefold: firstly, from the arbitrary executions carried out by IS security bodies on an almost daily basis; secondly, from a total lack of protection during the military offensive; and thirdly, those who survived the fighting were considered by SDF to be IS activists and have been imprisoned without trial ever since.

The Limits to the Collaboration with Kobani Health Authority: The Case of the Hospital

At the end of November 2017, MSF’s emergency cell in Paris sent me to Kobani to support the teams on site who were having difficulties working in the city’s hospital. Once on site, the decision was taken to cease our support to Kobani hospital, as the terms of the collaboration discussed six months previously were no longer being respected. MSF’s support was supposed to comprise free healthcare for the local population and people injured in the military offensive on Raqqa, as well as financial and material support and international staff to help the local medical teams with patient management. After six months of partnership, the findings that I presented to the Kobani Health Authority at a meeting on 1 December were extremely negative. I set out the reasons for our departure. MSF’s international staff were unable to treat the war-wounded arriving from Raqqa (the offensive had ended in October 2017, but there was still a large number of people in the town with injuries from explosive devices). In fact, the hospital’s local surgeons were systematically referring them to other hospitals, such as the one in Tell Abyad (a mainly Arab town about an hour’s distance from Kobani), or others at least a four-hour drive from Kobani. During the meeting, the Kurdish authorities informed us that they had decided six weeks previously not to admit any more wounded from Raqqa, as they had ‘done their bit and it [was] now up to other hospitals to take over, Tell Abyad and the others.’Comment noted during this meeting.

As a result, discrimination between Kurdish and Arab patients had been introduced. In Kobani, more than 80 per cent of surgical cases were not urgent, whereas Tell Abyad was overflowing with patients seriously injured by explosive devices in Raqqa and in need of an urgent operation. Another problem was that the region’s medical authorities had diverted some of the drugs brought by MSF to the military hospital. This was causing stock-outs and obliging patients to buy drugs from private pharmacies that they should have been receiving free-of-charge from MSF at the hospital.

The Political System in North-East Syria

It took an in-depth investigation (different visits, observations, meetings, exchanges and analyses) to identify and understand the roles of the different administrative authorities cited above. On the international stage, the Kurds were generally presented as being politically cohesive and establishing a political model described by some Middle East observers as progressive. In reality, the PYD is the Syrian branch of the PKK, itself in competition with Barzani’s KDP for the leadership of Kurdish nationalism. So in fact, there were deep divisions between these two parties. Furthermore, since taking power in the region, the PYD had snuffed out all political opposition, whether from Kurds or Arabs, and violently suppressed all demonstrations, going so far as to torture or kill potential opponents (International Crisis Group, 2013: 26). The PYD had in fact established an authoritarian regime far removed from the social contract drafted in December 2016 (Figure 1).Declaration made at Rmeilane where the Constitution of Rojava proclaimed in January 2014 becomes the social contract of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, setting up a federal system, which is rejected by the Syrian government.

Under this regime, membership of the party seemed to take precedence over Syrian identity and especially over the interests of the local population. According to local sources, the real political and military leaders were the non-elected executives of the PKK. All the posters on the roadsides and buildings, official or not, made constant reference to the PKK’s leader imprisoned in Turkey. The few Syrians who dared to question the system described it as a carbon copy of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, adding that the latter’s effigy had simply been erased and replaced by that of Abdallah Öcalan.

Figure 1

MSF France’s Experience in Qabassin

MSF first came into contact with ISIL in Syria in 2013. At the time, it was just one group among many, but ISIL very rapidly became a distinct, singular and hegemonic force proclaiming to be building a new State. This new group and its meteoric rise in Syria surprised a good many field operators and foreign observers. For MSF France, its first and only experience of relief operations in an area administered by ISIL was in the city of Qabassin from May 2013 to August 2014. Over this same period, three other MSF operational centres were working in ISIL-administered areas: MSF Spain in the governorate of Aleppo, MSF Holland in the governorate of Raqqa and MSF Belgium in the south of the Idlib governorate.

MSF France was looking to work in areas not being bombed by the Syrian regime and, in May 2013, after conducting the necessary analyses and research, it opened a hospital in the town of Qabassin, near Al-Bab, in the governorate of Aleppo. During the setting-up phase, MSF’s main interlocutors were the predominant institutions, i.e. the local municipal council and the Islamic Court, but also a number of politico-military groups, notably AS, FSA, JAN and the PYD.

On 17 August 2013, after a day’s fighting, ISIL took control of Qabassin. The same day, MSF’s personnel met ISIL’s combatants when they brought their wounded to the hospital. ISIL’s seizure of power had a direct consequence on the number of MSF international staff: nine out of fourteen left the mission after a team reflection on site. The origins of ISIL – an offshoot of Al-Qaida in Iraq – and the fact that its fighters wore explosive vests were preponderant factors in the decision-making.

On 19 August 2013, the emir of ISIL in Qabassin met with MSF’s coordinator to whom he had already addressed a written undertaking guaranteeing the protection of MSF’s hospital:

In the name of Allah the most Beneficent, the most Merciful. Praise be to Allah, peace and blessings be upon his prophet Muhammad. Henceforth, the MSF hospital will continue to treat all cases without discrimination. MSF will consult Islamic State in Qabassin in the event of problems at the hospital. Islamic State assumes responsibility for protecting the hospital from danger. All the doctors, men and women, will continue to work in the hospital.Letter from the emir of ISIL in Qabassin.

According to Islamic case law, this written commitment constituted an Aman, or security pact (a sort of safe passage enabling non-Muslims to benefit from protection for a limited period).

In addition to the guarantee of security given to MSF’s staff, it is interesting to note the group’s openness to maintaining the gender mix in the MSF hospital and to permitting treatment of all patients without discrimination. In the local context, this meant the right to treat PYD/YPG militants. In fact, members of MSF’s Syrian team had contacted the local ISIL leaders to explain that without this non-discrimination ‘clause’, MSF would probably cease its activities. It was clear that ISIL did not want its arrival in Qabassin to be associated with the closure of the town’s only hospital. In addition to the letter from the emir of ISIL in Qabassin, MSF also received written support from important institutions such as the local municipal council and the Islamic Court of Al-Bab, affirming that they expected MSF to pursue its activities and that it was in charge of the hospital’s management. These institutions and the politico-military groups behind them were in fact undertaking to assume the role of mediator should relations between ISIL and MSF become tense in Qabassin.

From August to December 2013, the issue of whether to stay or to go was the subject of much debate between MSF’s field coordinator in Qabassin, the coordination team based in Turkey and the operational managers at HQ in Paris. An important factor to consider was the relatively low level of medical activity given the high level of risk involved. Indeed, the project was affected by several incidents in November and December 2013, and events in the north of Aleppo governorate, where MSF Spain was operating, were also taken into account (the arrest and hostage-taking of the occupants of a vehicle in Aleppo in August 2013 and the assassination of a Syrian surgeon working for MSF Spain the following month).

In Qabassin, neither the Syrians nor MSF’s expatriate staff were directly affected by ISIL’s seizure of power, which changed very little in the day-to-day lives and work of MSF’s teams – although, in the first brief discussions with them, ISIL’s representatives made no secret of their totalitarian intentions. Moreover, since September 2013, ISIL propaganda in north-west Syria had been accusing foreign doctors of being enemy spies – a ‘status’ that until then had been reserved for foreign journalists. But, in Qabassin, the first real concerns were felt on 4 November 2013 when three ISIL fighters requisitioned an MSF ambulance, promising to return it in a few days. The president of MSF France left for Qabassin with the new head of mission and met with the emir of Qabassin, the emir of Al-Bab and a Chechen commander in Atmeh. Security guarantees were given to ensure the project would keep running and encourage MSF’s international team to stay.

On 18 December, another MSF ambulance was requisitioned. It was returned three days later – fitted with new tyres. This incident rekindled a difference of opinion between a project coordinator in Qabassin who was sceptical about maintaining activities in these conditions and a head of mission (the coordinator’s line manager) based in Turkey who was less convinced, not seeing this as the critical incident that should lead to MSF’s withdrawal.

On 2 January 2014, five expatriates from MSF Belgium were taken hostage in Bernas in Idlib governorate during a rebel offensive against ISIL. Two days later, a contact in Qabassin informed MSF France that the same type of offensive was being prepared locally and advised sending the international teams to safety in Turkey. They left the next day (Neuman and Weissman, 2016: 215). During the five months that it took to secure the hostages’ release, medical activities were maintained by the Syrian staff, some of whom received threats and were occasionally arrested. Following this release, representatives of ISIL in Qabassin asked MSF to come back. However, on 21 August 2014, MSF officially announced the end of all its operations in ISIL-controlled territory after having vainly attempted to obtain guarantees from the highest level of the organisation.

Why and How MSF Maintained Its Relief Operations in Qabassin

Before seizing power, ISIL already controlled the main point of entry to the town. Once in charge, it tolerated the presence of other armed groups, maintained existing institutions (local council and Islamic court), but put its own parallel institutions in place, enabling it to identify both its supporters and its opponents. As mentioned earlier, ISIL had also authorised MSF to continue providing free medical care. Tolerating the presence of MSF was part of a broader strategy on the part of ISIL to ensure basic services for the local population, so the interests of the two organisations converged. According to the periodisation described by Jean-Hervé Bradol when managing MSF’s project in Qabassin, this strategy was part of the ‘honeymoon phase’:

As I continued to mull over the situation, I thought the second phase of the relationship between local populations and global jihadists could be best described as the ‘honeymoon phase’. In some towns, the jihadists’ seizure of power has led to a degree of temporary improvement in public security and a reduction in the price of staple foods. The first pay-backs seem minor (stricter dress code for women, closing of businesses during Friday prayer, ban on the sale and use of tobacco, etc.) given the, albeit short-lived, improvement in public security and purchasing power of a population previously subjected to a violent dictatorship and the depredations of various armed political and criminal groups. That is what happened in our town [Qabassin] in late summer 2013. (Bradol, 2015)

At this stage, other than the destruction of the tomb of a saint, the change in power was yet to disrupt the day-to-day lives of the population, or MSF.

The Different Initiatives Taken in Government-Controlled Areas around Damascus

From 2011 to the present day, MSF has repeatedly sought the Syrian government’s permission to intervene in the areas to which it controls access. In 2012, rebel enclaves appeared, encircled by the loyalist Syrian army that gradually tightened its stranglehold by adopting siege strategies and controlling all humanitarian convoys. For MSF, the objective became to maintain the provision of medical supplies to some of these areas, but only by negotiating with Damascus would it be possible to get aid through in sufficient quantity and of acceptable quality. Various attempts were made to contact the Syrian authorities using a number of channels that I have split into three categories: attempts at direct contact, the ‘BRICS’ (Brazil, Russia, China, India, South Africa) card and the Russian option. This article does not cover the full range of initiatives undertaken by the whole of MSF.

For those representatives of MSF in favour of pursuing attempts to work with Damascus despite the overt hostility of Syrian officials who were accusing us of supporting ‘terrorists’, the aim was not simply to provide assistance to populations whatever their camp, but also to ensure a balance in MSF’s political positioning. Indeed, in the eyes of these MSF managers, the action of our organisation – presented as ‘western’ – was suffering from a bias due to insufficient activity in areas controlled by Damascus, Lebanese Hezbollah, Tehran and Moscow. This explains their dogged perseverance in requesting work permits from the authorities of what was perceived as the ‘Shi’ite camp’.

Direct Contacts

Between January 2011 and December 2013, several official requests were sent by the president of MSF International and MSF France’s General Director to the Syrian foreign affairs and health ministries seeking permission to work out of Damascus – and also informing them that MSF had decided to work in rebel zones.

Two of these contacts were particularly consequential. In May 2012, after a meeting between the president of MSF International in Geneva and the president of SARC, authorisation was obtained to send a donation of medicines and medical equipment to SARC. In August 2012, this donation arrived in Damascus where SARC took safe delivery of it. Meanwhile, in June 2012, the General Director of MSF France informed the authorities in Damascus, via Syria’s permanent mission in Geneva, that an MSF team had entered Syria to work in a medical and surgical unit in the rebel zone in Idlib province. This announcement was intended to guarantee that this unit would be respected and protected from attacks. One week later, the foreign ministry made the following response, also via the permanent mission in Geneva:

The MSF team entered Syria illegally; the Syrian authorities are no longer responsible for its security and ask that it leave Syria forthwith. We would remind you that the Syrian authorities only agreed to a delivery of medicines and medical equipment without the presence of your organisation on Syrian soil and without politicising this initiative, with SARC and ICRC in charge of distributing the aid to the needy.Letter of 29 June 2012 from the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

When, in 2014, an MSF team was kidnapped by ISIL, no contact was made with Damascus. However, between January 2015 and April 2018, various other official requests – always via Syria’s permanent mission in Geneva – were addressed to the offices of the President, the Prime Minister and the First Lady, as well as to the foreign affairs and health ministries and SARC – to no avail.

The ‘BRICS’ Card

In October 2012, a meeting was organised through the South African Embassy in Damascus between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a delegation from MSF South Africa’s office. Following this meeting, the MSF delegation was put in touch with the health ministry and SARC. In May 2013, an agreement protocol was signed between MSF’s South Africa office and SARC for a maternal health project in Damascus (Al-Zahera hospital). MSF thus formed an international team of five volunteers from countries designated as emerging by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS). The project never saw the light of day, as the volunteers were unable to obtain a visa.

The Russian Option

The first approach to Russia was made in March 2012. In a letter to the Russian foreign affairs minister, Sergei Lavrov, the president of MSF International asked for his assistance to set up a meeting with the Syrian authorities. This letter was then forwarded to the Syrian authorities by the Russian embassy in Damascus. The Syrian response came a week later and simply stated that all official correspondence should be sent via its representation in Geneva.

At the end of July 2016, after the Russian government had announced the opening of humanitarian corridors and the implementation of relief operations for western Aleppo (under siege at the time), MSF’s office in Moscow approached the Russian defence ministry. This ministry organised a meeting in Damascus at the end of August 2016 between a delegation made up of members of MSF Belgium and MSF Switzerland and the Syrian health minister and vice-minister of foreign affairs. The discussions resulted in an agreement for a project to provide physiotherapy for the war-wounded and primary healthcare for displaced people in the region of Latakia. However, the project was not able to start in the October as planned, as MSF teams were unable to obtain visas. Meanwhile, MSF had sent a proposal to the Ministry of Health for a full charter cargo of medical equipment and a surgical team to be sent to western Aleppo. No response here either.

A final attempt was made in June 2017. MSF signed an agreement protocol with the Association of Doctors of the Russian Federation foreseeing cooperation between the two parties in order to operate in conflict zones, notably those controlled by the Syrian government. This cooperation never saw the light of day.

This experience of relations with the Syrian government showed that it was only possible to meet with the Syrian government in Damascus with diplomatic assistance from the governments of South Africa and Russia. Even then, and despite signing agreement protocols, MSF was never allowed to work in the government-controlled zone. Consequently, over the entire period studied, most of the aid in this zone was controlled by the Syrian government. This aid was discriminatory (Damascus choosing the recipients); disproportioned (88 per cent of aid was allocated to government-controlled areas in 2016) (The Syria Campaign, 2016) and limited (Damascus imposed restrictions on the contents of humanitarian convoys). Each time discussions seemed to conclude in the possibility for MSF to send teams to Syria, these teams were refused entry visas. The main reason was the cross-border relief operations conducted without the authorisation of the Syrian government, as evidenced in the official speech by the Syrian representative to the United Nations in April 2018:

It appears Médecins Sans Frontières are in Syria without the approval of the Syrian government. Similar to ISIS, they entered the country without our approval. Médecins Sans Frontières are similar to smugglers without borders, criminals without borders, opposers without borders, agents without borders, aggression without borders, and terrorists without borders.Transcript of the speech given by Bachar al-Jaafari, Syrian ambassador to the UN, at the Security Council on 17 April 2018.Transcript of the speech given by Bachar al-Jaafari, Syrian ambassador to the UN, at the Security Council on 17 April 2018.

Conclusion

From 2012 to the present day, I’ve had the opportunity to monitor and analyse the Syrian situation and all the humanitarian initiatives undertaken in Syria. Over the course of my different missions, I’ve also been an actor in and direct witness to MSF’s relief operations, as well as an observer of the conflictual and heterogeneous environments in which they were run.

Drawing on these experiences, I have related the questions and concerns that occupied me intellectually and described for each zone the constant adaptations made to allow MSF to put in place and maintain its relief operations. Here is a summary of the issues that arose in the different areas of operation.

In the north-west, the issue was the need to switch from a direct management to a remote management mode, with Syrian colleagues pursuing MSF’s relief operations in an environment where the kidnapping of journalists and then aid workers had become a common occurrence. This approach showed that it was possible to maintain activities even when ‘jihadist’ groups like Hayat Tahrir Sham (HTS) have control over the area.

In the north-east, the experience was one of ‘democratic confederalism’ – a system which proved unable to prevent discrimination against the Arab populations in accessing care at the MSF-supported hospital in Kobani. In this same region, information on the war crimes committed by the anti-IS coalition received little coverage, especially the offensive on the city of Raqqa, as the media was busy denouncing the wrongdoings committed by IS.

I then explained how MSF was able to operate in the city of Qabassin under ISIL control until the group became too violent.

Finally, there were several attempts to negotiate with the authorities in Damascus while they continued to commit mass crimes: persecuting medical personnel, bombing civilian populations, targeting hospitals and using siege tactics to force rebel areas to surrender. These crimes did not prevent the United Nations and Red Cross movement from allocating the majority of their aid to the Syrian government.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasise that the Syrians were and remain in the forefront of the country’s relief effort. Through charitable organisations (most of which existed before the conflict), informal aid networks, new institutions born of the rebellion and the initiatives of organisations formed by the Syrian diaspora, endogenous solidarity significantly outweighs international relief efforts.

Bibliography

- Baczko, A., Dorronsoro, G. and Quesnay, A. (2016), Syrie. Anatomie d’une guerre civile (Paris: CNRS Éditions).

- Bradol, J-H. (2015), ‘How Humanitarians Work When Faced with Al Qaeda and the Islamic State’, CRASH, 20 February. www.msf-crash.org/en/publications/war-and-humanitarianism/how-humanitarians-work-when-faced-al-qaeda-and-islamic-state (accessed 6 November 2016).

- Burgat, F. and Paoli, B. (eds) (2013), Pas de printemps pour la Syrie: Les clés pour comprendre les acteurs et les défis de la crise (2011–2013) (Paris: La Découverte).

- International Crisis Group (2013), Syria’s Kurds: A Struggle within a Struggle, Middle East Report, no.136 (Brussels: ICG).

- Khaldi, H. (2017), ‘A Rakka, plus encore qu’à Mossoul, les civils sont laissés pour compte’, Le Monde, 1 August. www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2017/08/01/a-rakka-plus-encore-qu-a-mossoul-les-civils-sont-laisses-pour-compte_5167447_3232.html (accessed 16 September 2017).

- Médecins, Sans Frontières (2012), ‘En Syrie, la médecine est utilisée comme une arme de persécution’, press release, 8 February. www.msf.fr/communiques-presse/en-syrie-la-medecine-est-utilisee-comme-une-arme-de-persecution (accessed 4 September 2017).

- Neuman, M. and Weissman, F. (eds) (2016), Saving Lives and Staying Alive: Humanitarian Security in the Age of Risk Management (London: Hurst & Co.).

- The Syria Campaign (2016), ‘Taking Sides: The United Nations’ Loss of Impartiality, Independence and Neutrality in Syria’, http://takingsides.thesyriacampaign.org/ (accessed 6 November 2016).

To cite this content :

Hakim Khaldi, “Humanitarian Field Practices in the Context of the Syrian Conflict from 2011 to 2018”, 15 mars 2021, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/war-and-humanitarianism/humanitarian-field-practices-context-syrian-conflict-2011-2018

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute