A “partnership” experience, A guided reading of Che Guevara's diary in Congo

Yann Santin

Operational partnerships between two organisations are a practical approach to humanitarian responses. MSF considers such partnerships when the objective it is pursuing in a country is similar to that of an existing national organisation, and when there is potential for synergy between these two entities.

I would like to take a bit of a detour by looking at an experience that is in some ways similar: when Che Guevara tried to lead the revolution in Congo - Zaire by supporting the organisation of the guerrilla movement in the east of the countryThe parallel could cause perplexity, given the nature of the actors and the course of the events. Naturally, the aim here is not to compare our actions or to disqualify the partnership approach..

The context

In 1965, Ernesto Che Guevara says goodbye to Cuba. Rather than reap the fruits of the revolution in Havana, he decides to go and sow the seeds in lands yet to be freed. The struggle against imperialism is a global affair. To him, Africa is a strategic and crucial terrain: it is from their colonies that the imperialists draw the resources that serve their power. And since rebel movements are brewing, it is essential to support them. In eastern Congo, a People's Republic has just been declared and stands against the Belgium and American-supported government forces.

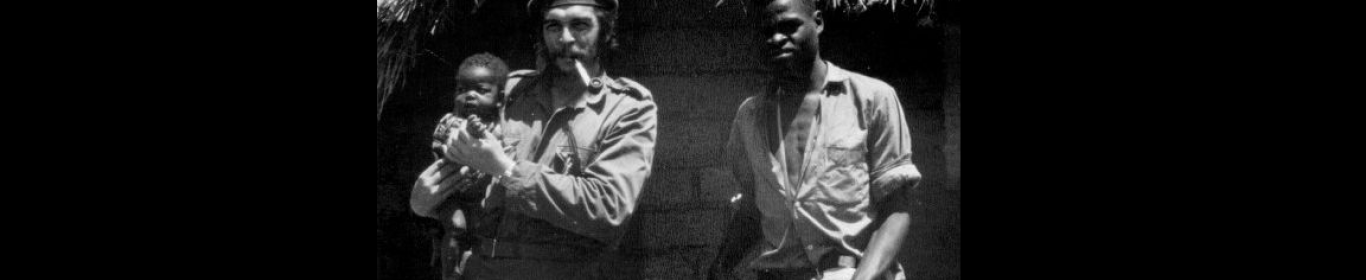

Socialist Tanzania harbours the rear bases of the Congolese insurgency, and so Che sets off to meet with its leaders. Of them, the young Laurent-Désiré Kabila stands out as the most promising. The two shared a common objective: to overthrow the power affiliated to the Westerners. Che offered him his support - instructors and weapons - which was immediately accepted.

A few weeks later, Guevara crossed Lake Tanganyika at the head of a squad of Cuban fighters: soldiers who had acquired solid experience of the maquis in the tropical mountains of their island. Hardened and carried by their revolutionary faith, they were ready for all sacrifices. They had the support of Fidel Castro, who was willing to supply them with men and equipment throughout their expedition. These men’s rustic profile and their expertise in armed insurrection met the conditions of the Congolese jungle and the needs of the rebels: they required equipment, their military technique was rudimentary and the various fronts lacked organisation. The combination of these two forces therefore held the promise of great achievements.

But seven months after having set foot in Kivu, in the midst of a debacle and in the grip of frank hostility towards them, the Cubans give up. From setbacks to disillusionment, their mission has been a long road to ruin.

It is this experience that Che writes about in his diary: a lucid account for those who will follow him, to prevent them from repeating his mistakes. His sharp pen and remarkable sincerity lead us into a dramatic and comical adventure. This is the story of a failure. It descends into anecdotal detail, as one would expect in an account of episodes of a war, but this is modified by observation and a critical spirit as I believe that, were this account to have some merit, it would be to allow certain experiences to be drawn out that might be useful to other revolutionary movements. His report, kept secret by the Cuban government for 34 years, was finally made public and translated into English (The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, Grove Press, 2001Subsequently published under various titles by several publishers, most recently: Congo Diary - Episodes of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, Seven Stories Press, 2021.).

Symptoms of failure

What is the Cubans' approach? They placed themselves under the orders of the Congolese command, but with a margin of autonomy in the organisation of their support to the troops. Their first objectives are relatively simple: it was a question of training men to shoot, to stage ambushes and to teach them certain military principles of organisation that would allow them to concentrate all the firepower on the point under attack. As for the method, it consisted of establishing a central training base with Cuban instructors and applying what they have learned through tactical actions of progressive difficulty, carried out by mixed units initially commanded by the Cubans. The plans seem clear, the ambitions attainable, and the newcomers are confident:

Our compañeros arrived bursting with optimism and good intentions, thinking that they would march triumphantly through the Congo.

However, what the Cubans propose to their Congolese comrades in the field does not seem to trigger much interest from them.

Again we began the fatiguing task of teaching the basic elements of warfare to people whose commitment was not obvious, in fact, we seriously doubted they had any commitment at all. In this way we desperately scattered seeds around us in the hope that some would germinate before the bad times came.

The outsiders find themselves paralysed by the lack of enthusiasm from the Congolese soldiers for their proposals. They are unable to extricate themselves from the multitude of events that thwarted their initiatives. They were mired in the magma of contradictory information. The nature and characteristics of the resistance groups make them impervious to any attempt at organisation on the part of the Cubans. In fact, no base is set up, no training plan materialised and the few attempted ambushes all ended in fiasco.

Our three priorities – shooting, ambush technique and the concentration of units for major attacks – were never achieved in the Congo.

As time goes by, the objectives become increasingly distant.

We had been there nearly two months and still had achieved absolutely nothing. The problems posed by the things I have described were accumulating in such a way that I was beginning to change my time frame. Five years was a very optimistic target for the Congolese revolution to reach a victorious conclusion.

A quick glance at the chapter headings provides an eloquent picture: ‟A Hope Dies”, ‟The Patient Grows Worse”, ‟The Beginning of the End”, ‟Disaster”, ‟The Whirlwind”, ‟The Collapse”.

According to those close to me here, I have lost my reputation for objectivity by maintaining an unfounded optimism in the face of the actual situation.

The disappointments encountered by Che and his men are astonishing. Their consternation at the turn of events and the adversity in which they are sinking becomes tragically comic. As the setbacks continued and the government troops advanced, they adapted their strategy to salvage what could be salvaged from their mission. In the end, their ambitions get reduced to gathering a core group of a few Congolese soldiers, tightened around the Cubans and autonomous from the rest of the rebellion - in other words, breaking away from it - in order to sow the seeds of a new army to come. But even this small group does not go beyond the stage of hope. Soon everything falls apart and they are condemned to flee. In the end, the only tangible and unifying effect of all their efforts will have been the development of a growing mistrust towards them, as the Cubans left the field as scapegoats for the series of military defeats.

The reasons for failure

Behind the cascade of unfortunate twists and turns lies a deep misunderstanding of the partners' objectives and motivations. The gap between the Cuban conception of what a liberation army should be and the social and political nature of the Congolese guerrilla movements is abysmal. Fundamentally distinct phenomena lie behind the same name and the apparent proximity of the causes and forms of insurrection. The reasons behind the existence of Cuban and Congolese soldiers had nothing in common. The concept of revolution of one did not correspond to any reality of the other. In other words, the spirit and the device that Che Guevara was planning to transfer to Eastern Congo were not adapted to the local ecosystem.

In all wars of liberation like this, a fundamental element is the hunger for land arising from the great impoverishment of a peasantry exploited by the latifundists, feudal lords and, in some cases, capitalist-type companies. In the Congo, however, this was not the case. There are no industrial workers and I saw no signs of wage labor. The currency does not penetrate very deeply into the relations of production. Imperialism shows itself only sporadically in the region. One of our compañeros said in a joking tone that all the anti-conditions for revolution are present in the Congo. What could the Liberation Army offer this peasantry? This is the question that always bothered us.

Over and above this fundamental inadequacy, a set of difficulties are added to the overall failure. Thus, the Congolese social structures were approached rudimentarily and perceived as obstacles to the organisation of the revolutionary apparatus desired by the Cubans.

Obviously there can be no advance unless it leads toward destruction of the tribal concept. People were not seen as individuals, but rather in terms of their tribe – a concept from which it was very difficult to escape; when a tribe was friendly, all its members were friendly; and vice versa when it was hostile. Apart from not helping the revolution to develop, such schemas were also clearly dangerous because – as we saw later – some members of the friendly tribes were enemy informers, and in the end nearly all of them became our enemies.

Che's men also found it difficult to reconcile some of their conceptions with those of their combat partners.

Lieutenant-Colonel explained that airplanes had no importance for them because they had dawa, a medicine that makes a person invulnerable to bullets. “I’ve been hit a number of times, but the bullets simply fell to the ground". This dawa did a lot of damage to military preparedness.

In short, there were numerous areas of misunderstanding between the two groups.

I spoke angrily to them in French; I rattled out the worst things I could think of with my poor vocabulary. But while the translator turned the “volley” into Swahili, the men looked at each other and guffawed with disconcerting naivety.

Finally, one of the aspects of the collaboration that preoccupied Che and on which he regularly tried to make an impact, without much success, was the quality of the relationship between the men.

It has been very difficult to achieve cordial relations between them and to get the Cubans to shake off their scornful elder-brother attitude towards the Congolese. We had not established entirely fraternal relations, and we always felt a little bit superior, like people who had come to give advice. It is also appropriate to analyse our own side. The great majority were blacks [Afro-Cubans]. This could have created empathy for and unity with the Congolese, but that did not happen. We didn’t see that it made much difference to our relations whether we were black or white; the Congolese knew how to identify each man’s personal traits. There was never the necessary integration, and this cannot be blamed on skin colour. Our men were foreigners, superior beings, and they made this clear all too often. Highly sensitive because of past insults at the hands of the colonialists, the Congolese felt it in the core of their being when a Cuban displayed any distain toward them.

To conclude

Cuban revolutionaries and Congolese rebels seemingly shared the same objective: that of defeating a common enemy. The Cubans had undeniable expertise and provided the Congolese with resources they objectively lacked and were eager to receive. The support of the guerrillas in their project was a promising initiative. But the replication was rejected.

Today we would speak of "lessons learned" to describe the exercise Che Guevara undertook. The fact that it is a narrative - and a riveting one at that - makes it possible to pass on this experience "not by abstractly listing the knowledge and skills it implies, but by sharing situations. The experience is "caught" in a story, and it is this narrative configuration that works towards its transmissibility and appropriation In the words of Christine Delory-Momberger, professor of education sciences ("Experience", in Vocabulaire des histoires de vie et de la recherche biographique, ERES, 2019, pp. 81-85)".

To cite this content :

Yann Santin , “A “partnership” experience, A guided reading of Che Guevara's diary in Congo”, 25 janvier 2021, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/blog/humanitarian-actors-and-practices/partnership-experience-guided-reading-che-guevaras-diary

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute

Add new comment