Claire Magone, Michaël Neuman & Fabrice Weissman

Head of Communications, Médecins Sans Frontières - Operational Centre Paris (OCP)

After studying communication (CELSA) and political sciences (La Sorbonne), Claire Magone worked for various NGOs, particularly in Africa (Liberia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Nigeria). In 2010, she joined MSF-Crash as a Director of Studies. Since 2014, she has been working as a Head of Communications.

Director of studies at Crash / Médecins sans Frontières, Michaël Neuman graduated in Contemporary History and International Relations (University Paris-I). He joined Médecins sans Frontières in 1999 and has worked both on the ground (Balkans, Sudan, Caucasus, West Africa) and in headquarters (New York, Paris as deputy director responsible for programmes). He has also carried out research on issues of immigration and geopolitics. He is co-editor of "Humanitarian negotiations Revealed, the MSF experience" (London: Hurst and Co, 2011). He is also the co-editor of "Saving lives and staying alive. Humanitarian Security in the Age of Risk Management" (London: Hurst and Co, 2016).

A political scientist by training, Fabrice Weissman joined Médecins sans Frontières in 1995. First as a logistician, then as project coordinator and head of mission, he has worked in many countries in conflict (Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kosovo, Sri Lanka, etc.) and more recently in Malawi in response to natural disasters. He is the author of several articles and collective works on humanitarian action, including "In the Shadow of Just Wars. Violence, Politics and Humanitarian Action" (ed., London, Hurst & Co., 2004), "Humanitarian Negotiations Revealed. The MSF Experience" (ed., Oxford University Press, 2011) and "Saving Lives and Staying Alive. Humanitarian Security in the Age of Risk Management" (ed., London, Hurst & Co, 2016). He is also one of the main hosts of the podcast La zone critique.

I. Stories

Sri Lanka. Amid All-out War

Fabrice Weissman

On 18 May 2009, the Sri Lankan government’s crushing victory over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) put an end to twenty-six years of civil war. Described by the government as the world’s largest humanitarian operation, the victorious Colombo offensive was praised as a model by many foreign military commentatorsCf. for example, V.K. Shashikumar, “Lessons from the War in Sri Lanka”, Indian Defence Review, 24, no. 3 (July–Sept. 2009); Lawrence Hart, “The option no one wants to think about”, The Jerusalem Post, 9 Dec. 2009. keen to demonstrate that a determined democratic army could vanquish a “terrorist” movement. In reality, victory came at the price of thousands of civilian deaths, and the enlisting of humanitarian organisations into a counterinsurgency strategy based on forced displacements and internment. MSF’s experience reveals the hard choices that all-out war imposes on aid organisations.

MSF withdrew from Sri Lanka in 2003, after working for seventeen years against a background of civil war between the government and the LTTE that began in the mid-1980s. A ceasefire agreement (CFA) was signed a year before MSF’s departure, leading to a return to relative normality and the hope of peace. Negotiations began under the copresidency of the European Union, the USA and other western countries, including Norway, which also headed a ceasefire observation mission, the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM).

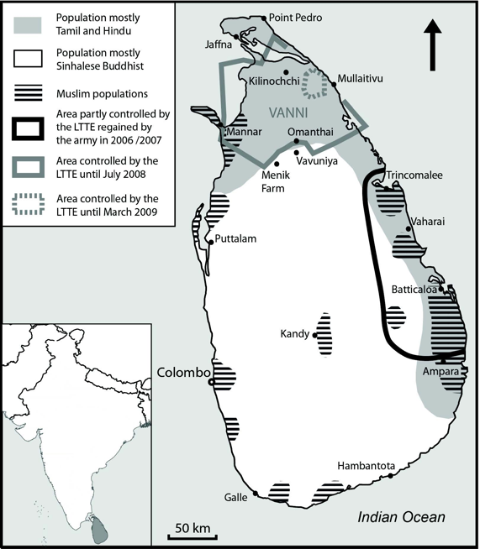

As early as 2003, the discussions stalled on the key question raised by the conflict: how to ensure peaceful coexistence between the Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim communities, representing 75%, 17% and 8% respectively of the island’s population. Although the parties did undertake to explore a federal solution to the conflict, talks became acrimonious once they got down to specifics or tried to agree on a transitional administration for the rebel areas (a third of Sri Lankan territory).Eric Meyer and Eleanor Pavey, “Bons offices, surveillance, médiation: les ratés du processus de paix à Sri Lanka” [Good offices, surveillance and mediation: failures in the Sri Lankan peace process], in Critique Internationale, no. 22 Jan. 2004, 35–46, p. 37.

A return to warfare seemed imminent when the Sri Lankan coasts were hit by the tsunami on 26 December 2004. Once the emergency response phase ended, management of reconstruction aid rekindled the conflicts over sovereignty between central government and the separatists. In late 2005, attacks, assassinations and abductions escalated in the north east of the country, fuelling a climate of terror. As ceasefire violations increased the eastern provinces slipped into open warfare during April 2006.

From 2006 to 2007, the army regained control of Batticaloa and Trincomalee in the east, driving the LTTE northwards back towards its sanctuary in the Vanni. The following year, the government officially renounced the ceasefire agreement and tightened its grip around the Vanni, taking control of Mannar district in April 2008 before entering Kilinochchi district in July. In January 2009, the army launched its final offensive. The Tigers were boxed into an area of land along the coast that shrank from 300 km2 in January to 26 km2 in March, 12 km2 on 23 April then to 4 km2 on 8 May. They were wiped out ten days later and their leader was killed along with most of the political and military commanders.

The LTTE cause most of the ceasefire violations in 2005 to 2006, and was largely responsible for triggering the resumption of hostilities. During the presidential elections in November 2005, it urged the Tamil population to abstain, thus contributing to the victory of Mahinda Rajapaksa, a candidate hostile to the peace process and who narrowly defeated CFA negotiator and former prime minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe. According to Sri Lankan political pundit Jayadeva Uyangoda,Jayadeva Uyangoda, “The Way We Are. Politics of Sri Lanka 2007– 2008”, Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association, 2008, p. 7. the LTTE was then counting on a new confrontation to boost its leverage in future negotiations: a war of attrition would weaken the economy, divide the regime’s support base and isolate it internationally due to the war crimes and human rights violations it would certainly commit. Media coverage of the army’s violence was in fact the LTTE’s main political asset on the international scene.

Even before its official withdrawal from the CFA in January 2008, the Rajapaksa administration made it clear that it was not prepared to negotiate any longer. It used the rhetoric of the global “war on terror” following the events of September 11 2001 to put a security and antiterrorist spin on the conflict. Denying the existence of the “ethnic problem” at the heart of negotiations and political debate since 1987, the Rajapaksa administration declared the LTTE as the only obstacle to peace, and sought its military and political destruction.

In the face of rapidly advancing government troops, the LTTE dragged tens of thousands of civilians down with them. As the rebel territory shrank, the Tigers used increasingly violent means to dissuade civilians from fleeing to government-controlled areas, executing those that tried to flee and/or making reprisals against their families, and then, in January 2009, strafing, bombarding and launching suicide attacks on columns of civilians trying to reach government lines.Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, United Nations, 31 Mar. 2011.

Controlling the population was strategically essential to the LTTE for at least two reasons. First, it needed to enlist increasingly younger children to make up for its heavy losses, and second, by mixing fighters with civilians, it forced the government army to choose between two ills: slow down or even halt the offensive, or commit war crimes.

Denouncing the use of the population as a “human shield”, in November 2006 the government asked the ICRC and the SLMM to mediate so it could evacuate civilians living in combat zones to camps behind its lines. The Tigers opposed the operation. Colombo then described its offensive as a “humanitarian mission” seeking to “free innocent civilians held hostage by the LTTE”.Cf., for example, “Offensive to provide water, not to gain territory”, The Sunday Leader, Volume 13, Issue 4 Colombo, 6 Aug. 2006.

In reality, although the army claimed to “adhere to the zero civilian casualty (ZCC) policy”,Ministry of Defence—Sri Lanka, “Ultimatum to LTTE expires: terrorists ignore safe passage for stranded civilians”, 1 Feb. 2009, http://www.defence.lk/new.asp?fname=20090201_01. it did not let itself be troubled by the presence of aid workers and civilians during its push forwards. Camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs), hospitals, humanitarian convoys and food distribution sites were hit by government artillery and air strikes on several occasions.Report of the Secretary General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, UN.

Several hundred civilians fell victim to shells and bullets between 2006 and 2008, several thousand between January and March 2009, and tens of thousands between April and May 2009. According to unofficial UN figures, 7,000 civilians were killed between January and early May 2009, and 13,000 more in the last two weeks of the confrontation. International Crisis Group (ICG) put the figure for civilian deaths at not less than 30,000 during the northern campaign. The government only acknowledged 5,000 civilian deaths and blamed them on the LTTE.ICG, “War Crimes in Sri Lanka’, Brussels: International Crisis Group”, 17 May 2010.

Throughout the conflict, the government carried out an intensive propaganda war designed to mask the terrible human cost of its offensive. It stated that it was leading a “humanitarian war”, thereby justifying its co-opting of NGOs and UN agencies into its pacification policies. From 2006 to 2008, MSF tried in vain to resist. Then, in 2009, it attempted to become a major cog in the military-humanitarian machine in the hope of lessening its brutality.

2006 to 2008: The Government Makes the Rules

From 2006 to 2007, the recapture of the east left at least 250 civilians dead and several hundred wounded, according to local human rights organisations.UTHR(J), Can the East be Won Through Human Culling?, Special Report no. 26, University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna), Aug. 2007, http://www.uthr.org/SpecialReports/spreport26.htm.

The fighting displaced 160,000 people. They received various forms of aid from the government, NGOs and UN agencies invited by Colombo to set up in the army’s wake, but this only lasted a few months. In March 2007, by cutting off humanitarian aid and using threats, the government—with the support of the UNHCR— organised the forced return of displaced people to their towns and villages, now destroyed and placed under military rule.

The first government victories went hand-in-hand with escalating political violence (abductions, assassinations and threats) targeting Sri Lankan figures who openly criticised the new administration’s militarism and xenophobic nationalism. Foreign journalists and international NGOs were also the targets of intimidation. Exploiting Sri Lankan society’s distrust of NGOs since their arrival en masse in December 2004, a phenomenon Sri Lankans described as a “second tsunami”, the nationalist media regularly accused humanitarian aid organisations of being “war profiteers” and “stooges of the terrorists”.Cf., on this topic, Simon Harris, “Humanitarianism in Sri Lanka: Lessons Learned”, Feinstein International Center, Tufts University, Briefing Paper, June 2010, https://wikis.uit.tufts.edu/confluence/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=3667....

A grenade attack hit three international NGOs in the eastern provinces in May 2006, wounding three people. On 4 August 2006, seventeen Sri Lankan employees from Action Contre la Faim (ACF) were executed in their office in Muttur on the east coast, a few hours after pro-government forces recaptured the town. The assassination, an unprecedented event in the history of humanitarian action in Sri Lanka and for which the SLMM held the government responsible, was officially condemned by senior western diplomats and the UN. The government responded by creating an investigation commission, whose investigations led nowhere. From 2007 to 2009, more than ten humanitarian workers were assassinated, including several ICRC employees.

MSF’s Goals

Anticipating a renewal of hostilities, MSF’s French section sent several exploratory missions to Sri Lanka in the first half of 2006, which were soon joined by teams from the Dutch and Spanish sections. In July and August 2006, the three sections proposed opening surgical programmes in three hospitals in the government-controlled zone near the front lines in Point Pedro (northern front), Vavuniya (southern front) and Mannar (western front). Their shared objective was to operate eventually in Tiger-controlled zones, with the French section already proposing to open a mission between Batticaloa and Trincomalee on the eastern front, where the first population displacements had been reported.

However, none of the evaluation teams observed any urgent needs. Sri Lanka had qualified personnel and an effective healthcare system, thanks to the ambitious social policies adopted after independence. Furthermore, wishing to assert its symbolic sovereignty over all the national territory, the government had continued to run public services in rebel areas, paying health workers’ salaries and ensuring supplies for medical facilities. In addition, a great many humanitarian aid organisations that had arrived in the wake of the tsunami were still in the country in 2006.

In such circumstances, the operations proposed for Point Pedro, Mannar, Vavuniya and in Tiger-controlled territories were primarily about being prepared. MSF sought to expand its healthcare services and emergency response capacity in areas where the organisation expected the conflict to resume with the predictable consequences: a breakdown in medical supply lines, departure of local medical personnel and an influx of wounded and IDPs. MSF’s goal, even if not always clearly expressed (except by the Dutch section), was also to ensure an international presence in conflict areas in order to “bear witness to the plight of the population”, in the hope of encouraging the belligerents to exercise restraint in the use of violence.MSF-Holland, Sri Lanka Annual Plans 2008 and 2009.

Discord

As the first shells fired by the government’s “humanitarian mission” started to rain down on the eastern front in July 2006, the MSF-France teams thought they could obtain the necessary authorisations to launch their activities within a reasonable timescale. They felt that the organisation had acquired legitimacy in Sri Lanka through its presence on both sides of the front line from 1986 to 2003, and its response to the tsunami. By calling a halt to donations three days after the catastrophe, explaining that reconstruction was the responsibility of the state and that most emergency needs were already covered by the authorities and civil society, MSF had flattered national Sri Lankan pride.

The MSF teams soon lost their illusions. Despite support from the local authorities and the Ministry of Health, requests for import licences, visas and authorisations to travel within the country got lost in a bureaucratic maze. As failure followed failure, it became clear that no decision could be taken without the approval of the Ministry of Defence and the president’s entourage, whose grip on the state apparatus was tightening.

Starting in July 2006, the Ministry of Defence had indeed restricted access to the rebel zones affected by fighting (designated “uncleared areas”) to the ICRC and selected UN agency teams that were only allowed short visits. Other aid organisations had been asked to work in government-controlled zones behind the lines. Failing to negotiate special status, comparable to that enjoyed by the ICRC and UN agencies, the French section decided to exert media and diplomatic pressure. On 9 August 2006, it published a press release denouncing the murder of the ACF workers and the “lack of medical help [for] tens of thousands of people living at the heart of the military offensive”. A week later, it organised a series of bilateral meetings with western ambassadors and the peace process co-presidents, feeling that the latter “had the ear of the government”. In late August, MSF-France managed to meet with Basil Rajapaksa, special adviser to the president, and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, secretary of defence. Although the president’s two brothers assured MSF that it was welcome to work in hospitals designated by the Ministry of Health, they lost their tempers when the head of mission demanded access to rebel zones. MSF was accused of partiality towards the LTTE and of “wanting to tell the government what to do”.Interview with the former MSF-France head of mission on 24 Feb. 2011.

MSF found itself in a delicate negotiating position. In August 2006, it had no information indicating that the aid provided by the government, ICRC and UN agencies in the “uncleared areas” was inadequate. MSF estimated that the existing set-up would not be able to cope with the expected influx of wounded and IDPs, an assessment rejected by the government who claimed that the consequences of the conflict would be minimal and handled appropriately by the authorised agencies. In reality, these disagreements masked underlying discord: MSF was keen to use its freedom of speech to denounce the excessive use of force its teams might witness while the government was keen to limit the number of observers likely to reveal the war crimes it was to commit.

Crisis

On 30 September 2006, while head office was encouraging the MSF field teams to stand firm, the French section learned from the national daily press that it was subject to an expulsion order, along with MSF-Spain and five other international NGOs. This was confirmed the same day in a letter from the Department of Immigration ordering MSF teams to leave the country within one week due to “activities […] in contravention of the visa conditions”. The press blamed the expulsion on MSF’s pro-LTTE commitment: quoting Ministry of Defence sources, it claimed that the organisation had carried out “clandestine activities” for the Tigers under cover of post-tsunami reconstruction aid.Cf., for example “Four INGOs to be booted out over link with Tigers”, The Island, 30 Sept. 2006; “Ignominious departure for INGOs, under fire for alleged assistance to LTTE and non-implementation of post-tsunami rebuilding pledges”, The Sunday Times, 8 Oct. 2006.

MSF immediately asked for support from the embassies of the expatriates targeted by the expulsion measures. On 5 October 2006, the minister of human rights told MSF that the expulsion order was on hold pending the results of an investigation into its activities. The head of state had just met with the CFA co-presidents and officially declared that he “would continue to facilitate humanitarian access to the conflict-affected areas while keeping in mind security considerations”.

Nevertheless, MSF staff still had no work permits and remained publicly accused of pro-LTTE clandestine activities. In mid-October 2006, the heads of mission wondered what they could do to rebuild MSF’s reputation when there was little chance of a government retraction. MSF’s international president, who had come to support them in the wake of the expulsion, had tried to publish a denial in the local media, calling a press conference in the hope of “clearing MSF’s name”. Only two (English-language) newspapers reported it.

What safety guarantees should MSF demand from the authorities, the heads of mission asked themselves, when the ICRC had just come under grenade attack a few days after having been accused of pro-LTTE partiality by the press, and the Ministry of Defence had refused to meet with MSF, relegating the crisis to a visa problem that had already been solved. Should they be happy with the suspension of the expulsion order and recent press restraint (MSF-Holland) or demand a public statement of support announcing that proceedings were being dropped and guaranteeing MSF teams’ safety (MSF-France) in line with the international president’s publicly-expressed position? How long could MSF wait for work permits?

Although all the sections were wondering if they should pull out, only MSF-France seemed determined to put words into action; on 13 October 2006, the head of operations warned: “If we don’t see some concrete results soon, we will have to take the decision to leave the country because of the lack of humanitarian space”. Not everyone agreed with this option: could they turn their back on the country when all evidence pointed to the conflict being on the brink of escalating? What purpose would be served by one or more sections leaving? Should they simply redeploy their intervention resources to those areas where the organisation was accepted? Or stage a media event to put the government in an awkward diplomatic position and strengthen the negotiating position of the organisations that were staying put?

Compromise

The three sections finally chose to continue to negotiate. They stopped seeking an official denial, the abandonment of the investigation and a public statement of support, and ended up signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) allowing them to launch operations in three hospitals selected by the Ministry of Health. The question of access to “uncleared areas” was not raised. The projects opened in December 2006 and January 2007.

During the two years that followed, the medical-surgical missions in Point Pedro (MSF-France), Mannar (MSF-Spain) and Vavuniya (MSF-Holland) were not over-stretched. In 2007, most of the wounded and people displaced by war were concentrated on the eastern front, while in 2008 the operation to surround the Vanni had not yet caused many civilian casualties. MSF’s operations did nonetheless ensure continuity of healthcare (emergencies and surgery) in hospitals with insufficient specialists, dealing with supply breakdowns and the rigours of military occupation. In Vavuniya, MSF-Holland had to suspend surgical activities in March 2008 as the increased Ministry of Health teams made its presence redundant. MSF-Spain decided to close the Mannar programme after the army recaptured the district in late 2008, and left the country the following year.

The French section tried nevertheless to gain access to the eastern provinces where the army was making fast progress. In order to be allowed into the “uncleared areas”, it turned to the UN. In late October 2006, the resident UN coordinator endeavoured to negotiate a procedure with the government for designating organisations approved to work in rebel zones and, in November 2006, it obtained authorisation for access from the Ministry of Defence for twenty-one NGOs, one of which was MSF.

Having obtained their passes, the coordination team carried out an evaluation mission in Tiger-controlled areas close to Vaharai in February 2007. However, it did not manage to obtain the necessary authorisations to start up the project before the government forces recaptured the zone a month later, making the planned intervention irrelevant. In April 2007, it proposed providing support to the Batticaloa hospital as the surgical unit was overflowing after the army’s recapture of the coastal strip to the south of the town. Once again, Colombo’s administrative obstruction and the lack of human resources in Paris delayed the intervention. The surgical teams arrived in August 2007, at a time when the hospital’s activities had returned to normal and the eastern provinces were almost entirely pacified.

The French section settled for helping IDPs, providing modest support (mobile clinics, sanitation and distribution of essential goods) to around 30,000 of the 160,000 people caught in the midst of the government’s forced displacement/resettlement operation. It closed its programme in January 2008, without ever really looking at the issues raised by its participation in forced population transfers organised with HCR support.

In the end, only the Dutch section managed to set up in Tiger-controlled territories, although it was far from the combat zone. In May 2007, it opened a programme in the LTTE “capital” Kilinochchi which was not yet affected by the fighting. It chose to support the gynaecological, obstetrical and paediatrics units with a view to getting prepared.

But as the front came closer in the summer of 2008, bringing displaced civilians to Kilinochchi, difficult relations with the hospital’s medical staff forced MSF to limit its intervention to logistics aid for the waste treatment area and building latrines for the IDPs. On 8 September 2008, the government ordered all the humanitarian aid organisations other than the ICRC and selected UN teams to evacuate the Vanni.

MSF was one of the first organisations to leave the LTTE zones. Its immediate efforts to return encountered a categorical refusal from the secretary of defence, whom they met on 28 November 2008. Asked to pressure the authorities, the Indian and western embassies said they were powerless. Since 2007, Sri Lanka had been drawing closer to China, Pakistan and Iran, with which it had signed a series of economic and military agreements.

After three years of negotiation, as the conflict seemed on the verge of a decisive confrontation that would not spare the civilian populations, MSF had just one surgical programme in Point Pedro, a small-scale project supporting the Vavuniya health district, and very little hope of gaining access to conflict zones. Moreover, MSF was not comfortable with making its voice heard: since the 2006 crisis, it felt that public criticism of the government was likely to lead to expulsion or even physical reprisals against its staff. The MSF teams seemed completely at a loss as to what to do.

2009: All-out War and the Humanitarian Solution to the Tamil Question

Between January and May 2009, the fighting was concentrated on a constantly shrinking and densely populated area and the number of civilian victims increased sharply. In LTTE zones, the wounded had access only to rudimentary care provided by eight Sri Lankan doctors from the Ministry of Health who had refused to abandon their post. The ICRC, which continued to provide them with medical supplies overland then by sea until 9 May 2009, managed to transfer 6,600 wounded and seriously ill people as well as those accompanying them, a total of 13,000 people, to government-controlled areas.

The army evacuated almost 300,000 people from territories gradually recaptured from the Tigers. Soldiers escorted the survivors to transit zones where they were screened: people suspected of belonging to the LTTE were transferred to demobilisation camps, called “rehabilitation centres”, and the others to closed internment camps managed by the army and called “welfare centres”. Ringed by several rows of barbed wire, the camps were guarded by the army and police.

The largest “welfare centre” was at Menik Farm to the south of Vavuniya, in a marshy and isolated area. Its construction began in September 2008 and was coordinated by the army, which completed the first two zones of the complex. In early February 2009, Colombo asked for help from humanitarian agencies and donor countries in building five additional zones. The medical project included the opening of 1,400 beds in hospitals around the centre and installing five small hospitals and twenty health units within the centres. These “welfare villages” were intended to house 200,000 people for three to five years. Donors were very reluctant to finance construction of permanent internment camps, but ended up agreeing to support the emergency programme for a few months, in exchange for a commitment from the government to resettle 80% of displaced people by the end of 2009.

In February 2009, the announcement of the setting up of Menik Farm stirred up controversy both nationally and internationally, a controversy that grew fiercer in July. Sri Lankan, Indian and British members of parliament compared the “welfare centres” to “concentration camps”, reminiscent of those in Nazi Germany.Jeremy Page, “Barbed wire villages raise fears of refugee concentration camps”, The Times, 13 Feb. 2009. International journalists, who had been banned from going to Menik Farm other than during a handful of guided visits organised by the army, gave wide coverage to alarmist claims about health conditions in the camps. In July, British daily newspaper The Times claimed it had been told by senior aid sources that 1,400 people were dying in the camp each week,Rhys Blakely, “Thousands die in Tamil ‘welfare village’”, The Times, 10 July 2009. and added that the death toll lent credence to allegations of “ethnic cleansing” by the government. The press began to question the role of the UN and aid organisations. The UN was accused of “having hidden the scale of the massacres”,Philippe Bolopion, “L’ONU a caché l’ampleur des massacres au Sri Lanka” [The UN hid the scope of massacres in Sri Lanka], Le Monde, 29 May 2009. British aid to war victims was suspected of being used “to fund concentration camps”,Jeremy Page, “British aid for war refugees may be used to fund ‘concentration camps’”, The Times, 28 Apr. 2009. and the UN and NGOs of being “complicit in a large-scale detention operation”.“Sri Lanka, stop!”, Le Monde, editorial, 10 Sept. 2009.

Waiting in the Wings

Between January and 20 April 2009, MSF watched the crushing of the Vanni from afar. In late January 2009, the first civilians began to arrive in the government-controlled zone, making the Dutch section operational once more. The sick and wounded evacuated from the combat zones began to crowd into Vavuniya’s general hospital, where the number of hospitalised patients jumped from 365 to 1,004 between 1 February and 1 April. First one, then another MSF-Holland surgeon came to join the Sri Lankan team. MSF hired nursing auxiliaries to improve post-operative care. But it could do no more: the authorities refused to allow an anaesthetist and two extra expatriate nurses to join the team. They also opposed increasing surgical teams in the other hospitals which were taking in the wounded evacuated by the ICRC.

In Vavuniya district, the dozen internment camps set up in public buildings were soon overwhelmed, leading soldiers to transfer the first interned civilians to zones zero and one at Menik Farm in February. The military and health authorities in Vavuniya asked for support from the UN and NGOs to assist recently evacuated populations. The local authorities were seeking organisations to distribute special food supplements to the under-fives and pregnant and breast-feeding women in the internment centres, and the Dutch section agreed to help. Distribution began in mid-February 2009, despite the lack of any formal agreement from the Ministry of Health in the capital, which had made clear its wish to be the sole provider of medical and nutritional assistance in the camps. “[Local administrators] really want us to bring staff, no matter what they say in Colombo. We also got full access to all camps, and the army general [in charge of supervising the camps] gave us his personal cell number in case anyone objects”, reported the MSF-Holland head of mission.

In direct contact with the displaced and wounded coming out of the Vanni, the Dutch section played a part in disclosing the brutality of the regime’s counter-insurgency campaign and its internment policies. Between January and March 2009, it issued a press release and posted several updates on MSF websites describing the living conditions of civilians caught up in artillery fire in the Vanni and the lack of freedom for the displaced people interned in Vavuniya. Several MSF representatives talked to the international media about these issues. While the ICRC was claiming that “plain common sense dictate[s] that the civilian population should be urgently evacuated [from combat zones]”, “Sri Lanka: ICRC reiterates concern for civilians cut off by the fighting”, 4 Mar. 2009, http://www.icrc.org/eng/. MSF “called on all parties to the conflict to allow independent humanitarian agencies to provide medical aid to the wounded in the Vanni”.

With activities functioning only in Point Pedro, the French section took a more discreet approach. It limited itself to relaying some of MSF-Holland’s information and giving a number of interviews in which it expressed alarm at the bombing of civilian zones and health facilities, a practice already strongly condemned by the ICRC, human rights organisations, the UN and western embassies, which in February demanded a “humanitarian ceasefire” to spare civilian lives.

An Emergency Situation

On 20 April 2009, the army broke through the LTTE’s defensive lines and cut its territory in two, triggering the evacuation of over 100,000 civilians in just a few days. The final battle caused an additional 77,000 to be displaced between 14 and 20 May. The evacuated included a great number of wounded. On 21 and 22 April, 400 patients were admitted to Vavuniya hospital, where MSF and Ministry of Health teams operated day and night. In mid-May, the hospital had over 1,900 hospitalised patients, and just 480 beds. As army bulldozers cleared zones 3 to 5, the Menik Farm population rose from under 30,000 inmates to over 220,000 in five weeks. Forty-five thousand people were also interned in small temporary camps in Vavuniya district and 21,000 in camps in Jaffna, Mannar, Batticaloa, Trincomalee and Ampara.

From 20 April the two MSF sections set themselves three priorities: provide emergency care to IDPs in the transit zone, boost operative and post-operative capacity (notably by deploying a field hospital) and develop healthcare provision inside the internment centres. The local authorities, seemingly caught off guard by the scale and speed of the population displacements, proved receptive to most MSF proposals, even asking the Dutch section to open mobile clinics inside the camps “as soon as possible”.Office of the Regional Director of Health Services, Vavuniya, “To MSF-Holland Project Coordinator. Request for Medical Team to Work at IDP Camps”, 21 Apr. 2009.

In Colombo, the Ministry of Health opposed the proposals. The master plan it had just updated with help from the WHO and UNICEF gave the monopoly in healthcare and public health activities within the camps to the government and carefully selected partners. But Colombo was particularly interested in MSF’s proposed interventions outside the internment camps as they fitted in with its plans. On 16 May, the French and Dutch sections each signed a new Memorandum of Understanding with the Ministry of Health authorising them to launch three projects: open a 100-bed surgical field hospital opposite the Menik Farm detention centre (MSF-France), provide additional assistance for treating the wounded at Vavuniya hospital (MSF-Holland), and open a post-operative care unit in Pompaimadhu (MSF-Holland). Faced with an emergency situation, MSF chose to go along with the government’s action plans and made two concessions: it renounced, for the time being, negotiating access to transit zones and internment camps, and signed a MoU committing it to “strictly maintain the confidentiality of the information on service provision” and make “no comments […] without the consent of the Ministry of Health Secretary”.

As the programmes approved by Colombo opened in under two weeks, the teams tried to go beyond the authorised activities. When the second wave of IDPs arrived, MSF-Holland succeeded in negotiating at the local level the dispatch of a four-person team to the Omanthai transit zone (where it had tried in vain to intervene in April). From 16 to 20 May, MSF doctors helped with the triage of 77,000 survivors of the final offensive and with boarding them onto army buses heading for the internment camps. The team treated 750 patients, mostly with old wounds that had received little or poor care. All they could do was provide emergency treatment (cleaning wounds, administering antibiotics and pain relief), refer the 200 most serious cases to the hospital at Vavuniya, which they knew was overflowing, and hope that the wounded transferred straight to the camps would receive the care they needed to prevent them from developing crippling and/or fatal infections.

Some of the wounded were transferred to Mannar hospital. The ICRC, which had set up a surgical team in the hospital, reported 800 patients and contacted MSF directly to reinforce its teams. From 23 to 24 May, joint ICRC, MSF and Ministry of Health teams operated on sixty patients with old and infected wounds. But on 25 May as it had not received prior approval from the Ministry of Health, the hospital’s management received an order from Colombo to break off cooperation with the ICRC and MSF.

Doubts Arise

Access to camps then became a key issue for MSF. Since the government’s “humanitarian mission to rescue civilians held hostage by the LTTE” had turned out to mean carpet-bombing, then would the “welfare villages” turn out to be places where the Tamil population would be left to die?

Access to internment camps was strictly regulated; however, access was possible for national and international staff from MSF, fifty-two NGOs and UN agencies, except during several forty-eight-hour periods when the security forces carried out screening operations seeking to identify suspected LTTE militants. Even so, MSF was unable to get a precise picture of the health situation. Claiming the monopoly on producing numbers, the government banned any independent epidemiological surveys. The MSF teams had only an approximate idea of health conditions in the camps, based on their visual impressions, brief interviews with internees and longer discussions with hospitalised patients at Vavuniya and Menik Farm. They completed their rough assessment by sharing information with Sri Lankan health workers, national and international employees of other aid agencies, and the security forces, including a number of government officials who openly criticised Colombo’s refusal to authorise greater access to the camps for international organisations.

The general impression was that the two huge waves of internees in April and May had created considerable chaos, but that it had gradually been brought under control by the government and aid organisations coordinated by major-general Chandrasiri, the overall head of the internment complexes. The major-general presided over inter-agency coordination meetings and managed aid with an iron fist. In late May, OCHA noted that the camp was short of 15,000 shelters (out of 40,000), that half the latrines had been built and that 75% of water requirements were being met. In private, its representatives acknowledged that the aid services had deployed at an incomparably faster rate than, for example, the slow and chaotic response from the UN and NGOs in Darfur in 2004.

The ministry’s master plan seemed to draw straight from public health guidelines drawn up by the WHO and MSF, but the government appeared to have trouble implementing them, despite claiming the enlisting of 300 doctors and 1,000 nurses. The teams learnt from different concurring sources (the police, the morgue and the ICRC in charge of distributing body bags) that the number of deaths at Menik Farm was between ten and fifteen a day in late May. When set against the overall population of the camp, it corresponded to a daily mortality rate of 0.45 per ten thousand and, although this rate was much lower than the emergency thresholds used in Africa, it was three times higher than the national average. The detainees were not dying en masse, but the initial disorganisation of the healthcare system

(denounced by some of the Sri Lankan doctors who went on strike in the summer) was in all likelihood the cause of a higher death rate among physiologically weakened inmates, such as the wounded, the elderly, children and those suffering from chronic diseases.

In June, the two MSF sections made several proposals for interventions inside the camps (primary healthcare, nutrition, surgical consultations, mental healthcare, epidemiological monitoring, etc.). They were all turned down, more or less explicitly. This refusal increased the teams’ doubts and unease. Why was the government insisting on prohibiting MSF from carrying out any health activities within the camps? Was it trying to mask a serious deterioration in the health situation, or ferocious political repression?

The MSF-France teams working at the Menik Farm hospital were particularly puzzled. No more than 70% of beds were occupied, whereas the other outlying hospitals were still overflowing. With no control over selecting the patients arriving from the camps, MSF wondered what was behind the underuse of its hospital. How could it be sure that the most serious cases were being given priority? Were the patients subject to a politically-skewed selection process? Was the MSF hospital merely a propaganda tool for a government seeking to create the appearance of normality? At the head offices and in the field, many MSF members asked themselves if all the sections should leave the camps and denounce the regime’s detention policies, to which aid organisations were public health auxiliaries.

Making a Choice

Following a visit by head office in June 2009, the French section chose to stay put, although they were fully aware of the role the government had assigned them: contribute to maintaining public health order in the internment camps, the main function of which was to monitor and control “dangerous” populations and stifle any fresh surge in Tamil nationalism.Fabrice Weissman, “Welcome to the farm. MSF and the policy for interning the displaced people of Vanni”, report of the visit to Menik Farm and Colombo camps (Sri Lanka), 4–14 June 2009. Paris, Fondation MSF/ CRASH, July 2009.

Having decreed the abolition of minorities and thereby dispensed with taking their political aspirations into account, In July 2009, the president stated his belief in “my theory…[that] there are no minorities in Sri Lanka, there are only those who love the country and those who don’t”, cf., The Hindu, 6 July 2009. the Rajapaksa administration sought to reduce the citizens from the Vanni to beneficiaries of the state’s humanitarian benevolence, well-cared for, well-fed, well-housed and, most importantly, well-guarded. The Menik “Farm” symbolised this policy, which extended beyond the barbed wire, as illustrated by the Ministry of Defence’s decision to recruit 50,000 extra soldiers after the war was over. This last initiative lent credence to critics of the regime who denounced a pacification of the Vanni in the form of long-term military occupation.

The only concessions that the international actors (states, the UN, NGOs, etc.) could count on concerned the relaxing of the detention policy: transparency of the screening process, release of certain categories of internees and improved detention conditions. Head office felt that MSF should contribute to these improvements. MSF-France therefore sought to become an essential cog in the internment camps’ health system: in July, it expanded its hospitalisation capacity, improved its technical services (radiology, ultrasound, laboratories, etc.) and replaced the hospital tents with semi-permanent buildings. It also started to try and get some internees released on medical grounds.

This position was poles apart from the stance taken by other humanitarian aid organisations and donors, particularly the USA and the EU. Funding the camps to the tune of 700,000 dollars a day, in June 2009 the UN and its donors opposed the major improvements in aid standards demanded by the government (construction of permanent shelters and latrines with septic tanks, extension of healthcare infrastructures and the running water network, etc.) so as to underline the temporary nature of the internment camps. During the same period, most NGOs refused to distribute cement to consolidate the floors of the tent and plastic shelters. Yet the housing conditions were precarious. The tents and tarpaulins used throughout the zones (apart from zones 0 and 1 which had permanent structures built by the army) deteriorated rapidly while the latrines overflowed and a foul-smelling tide of mud flooded the groundsheets. In a strange reversal of roles, the government accused aid organisations of causing a “humanitarian crisis” and holding the IDPs hostage to make the authorities give in to their demands. The accusations grew fiercer in August 2009 when the first monsoon rains transformed the camps into open sewers. But images of flooded camps also served as a tool for mobilising opinion and were seized upon by human rights organisations and some Sri Lankan politicians who demanded “a prompt and rapid resettlement of displaced persons to their places of origin”.

The decision by General Sarath Fonseka, commander-in-chief of the Sri Lankan army and leader of the victorious offensive, to join the opposition and run against the outgoing head of state in the presidential elections planned for January 2010, had indeed placed the issue of IDP internment centre stage. Rajapaksa and Fonseka shared the same support base and were trying to attract the minority vote. In August 2009, the former commander-in-chief denounced the fate meted out to internees by the Rajapaksa administration. Combined with international pressure, these electoral concerns persuaded the regime to open the camps and initiate a fast-paced resettlement policy starting in September 2009. By 31 December over half the IDPs had already been sent back to their towns and villages, destroyed, mined and tightly controlled by the army and plainclothes security forces. The French and Dutch sections closed down their emergency programmes. The Menik Farm hospital never became the main hospital for the internment camps. Four thousand admissions were recorded between 22 May and 6 December including 585 suffering from war wounds. According to the information gathered from local health authorities, this 4,000 represented 5% to 10% of all hospitalisations from the camps.

Having returned to Sri Lanka believing that it benefited from a special status in the aid world, MSF found itself in an extremely delicate negotiating position, on a par with the other NGOs. Its weak position sprang primarily from the Tigers’ “human shield” strategy of victimisation, which subverted the humanitarian narrative into a propaganda tool to sustain a movement using totalitarian practices. Using the LTTE’s treachery as justification, the government showed a remarkable capacity for organising and justifying the subjugation of humanitarian aid organisations to its political and military interests. MSF found itself assigned the role of assisting in a pacification policy that had settled the ethnic question in Sri Lanka by bombings and military surveillance, providing humanitarian aid to populations decreed to be dangerous.

Under permanent threat of administrative obstruction and violent reprisals, MSF did not know how to get the political support it needed to resist. Lacking allies in Sri Lankan society, it looked to western states and the UN, whose influence was waning. MSF ended up accepting the government’s diktats, imposing the places, targets and mechanisms for intervention, while counting on bureaucratic flaws in the system and its internal pockets of protest to retain some degree of autonomy. MSF decided not to make use of its freedom of speech to attack a regime that was eager to appear to the world and its own society as the guarantor of a rule of law and democratic values. At the end of the day, MSF adopted a policy of opting for the lesser evil, aimed at improving the condition of survivors of an all-out war that no political power seemed capable of checking.

Translated from French by Nina Friedman

***

Ethiopia. A Fool’s Game in Ogaden

Laurence Binet

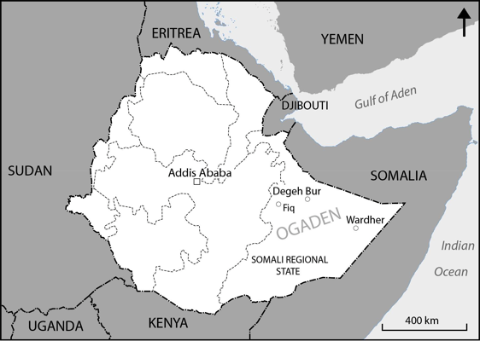

The Ogaden region in the Somali regional state of Ethiopia has been the scene of conflict between the Ethiopian federal government and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) separatist movement since 1994. In April 2007, the fighting intensified. After a series of rebel offensives, a wave of repression hit the region, which saw villages attacked and burned, violence and forced displacements, denial of access to wells and a blockade on all commercial traffic, vital to the nomads who inhabit the area. Jeffrey Gettleman, “In Ethiopian Desert, Fear and Cries of Army Brutality”, The New York Times, 18 June 2007.

In 2007, MSF’s objective was to provide care for the victims of the conflict. In a region with very few medical facilities and a dispersed population, this meant supporting health centres and organising mobile clinics to go where patients were in need of treatment.

Since the beginning of 2007, the Dutch section’s team had been trying to set up a programme in the Wardher hospital on the outskirts of the conflict, but the army regularly denied MSF access to the population living in the area. After a rebel attack near its base in July, MSF decided on a temporary evacuation that was followed by the authorities banning the organisation from returning. Before pulling out, during the few rounds of medical consultations it had managed to hold, MSF had been able to collect witness reports on the acts of violence committed by the warring factions.

During the same period, the Belgian section was prohibited from completing an exploratory assessment at the centre of the conflict zone in the area around Fiq where it was preparing to start up a programme and the ICRC, accused by the Ethiopian authorities of supporting the ONLF, was expelled from the Somali region.

No other humanitarian organisations were active in the conflict-ridden areas of Ogaden. The army’s distribution of WFP aid raised questions of impartiality as it was suspected of using the aid to reward people for keeping their distance from the ONLF.

In early September, after a series of diplomatic meetings with Ethiopia’s main donors and other stakeholders that brought few results, MSF held a press conference to condemn the government’s refusal to allow humanitarian organisations into the Ogaden region. MSF, “MSF Denied Access to Somali Region of Ethiopia despite Worsening Humanitarian Crisis”, press release, 4 Sept. 2007.

Accounts of human rights violations, documented by the Dutch section, were also cited at the press conference and reported by the international media. “Ethiopia Blocking Civilian Access to Medicine in Conflict Zone, Agency Says”, Associated Press, 4 Sept. 2007.

The government then accused MSF of violating its sovereignty and supporting the ONLF. “Ethiopia: Government Denies ‘Blocking’ NGO”, IRIN, Nairobi, 4 Sept. 2007.

The Belgian section was ordered to close down its long-standing programme for tuberculosis patients outside the conflict zone and the ban on the Dutch team returning to Wardher was maintained.

In the meantime, OCHA, responding to the alerts on the situation in Ogaden, issued in particular by MSF, sent a fact-finding mission which reported a worsening of the health and economic situation in certain areas:“Report on the Findings from the UN Humanitarian Assessment Mission to the Somali Region, 30 Aug.–5 Sept. 2007”. difficult access to water and food, shortage of drugs and therapeutic foods, and many cases of acute diarrhoea and measles. In November, OCHA obtained permission from the Ethiopian authorities for several international organisations to work in Ogaden. As the authorities were continuing to block the return of the Belgian and Dutch sections, the MSF movement encouraged applications from the Swiss and Spanish sections that went on to become some of the chosen few. OCHA also obtained the promise that WFP officials could be present when the army distributed food aid, a promise that was not to be kept.

In January 2008, the Swiss and Spanish sections started up medical and nutritional programmes in the areas of Fiq and Degeh Bur that were directly affected by the conflict and the Dutch section returned to Wardher, without authorisation but not officially banned either. But, in reality, by mid-January the operations of two sections were at a standstill. The team of the Dutch section was put under house arrest in Wardher after one of its lorries refused to stop at an army roadblock, and several national staff members were accused of spying for the ONLF. With no explanation, an MSF-Switzerland field team was also ordered to shut down its exploratory mission and forbidden to leave the hotel. Before the mission was suspended, the team had observed that the people it had encountered were victims of violence and suffering from shortages of water, food and medical care due to the restrictions on movement caused by the conflict. However, MSF headquarters was reluctant to draw overall conclusions from these events with regard to the situation in the region as a whole.

In March, the house arrest orders had only just been lifted when all the MSF teams were hindered, on the pretext that most of the expatriate staff members didn’t have work permits.“Letter from MSF International Office Secretary-General to Ethiopian Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs”, 31 Mar. 2008.

In May, a severe nutritional crisis necessitated the assistance of international organisations to conduct emergency relief operations in several Ethiopian states and the authorities took a more relaxed attitude to the question of work permits.

In the Fiq area, however, the MSF-Switzerland field teams were still paralysed and, in June, several national staff members were accused of spying and imprisoned. A month later, the Swiss section shut down its programme and issued a public condemnation of the administrative obstruction that was preventing it from providing relief to the population.MSF-Switzerland, “Ethiopia: Repeated Obstructions Lead MSF-Switzerland to Pull Out from Fiq, Somali Region of Ethiopia”, press release, 10 July 2008.

It also circulated a document to donors, international institutions and embassies denouncing the Ethiopian authorities’ exploitation of emergency food aid for political ends and the absence of a response from the United Nations.MSF, “Access and Response in the Somali Region: Mission Impossible? The Case of MSF-Switzerland in Fiq”, report, Dec. 2007–June 2008.

The other sections, hoping to be able to work within the limits allowed them and judging that they lacked solid evidence of the misappropriation of aid, did not join MSF-Switzerland in the condemnation.

In the following years, managing as best they could with the endless administrative hurdles, they instigated programmes to support health facilities in areas of ongoing, low-intensity conflict. They provided medical and nutritional aid to the inhabitants—who lacked such care even in times of peace—and medical care to Somali refugees in the transit camps on the border.

Conflicting Objectives

The issue of access to Ogaden in 2007 to 2008 was marked from the outset by a conflict between MSF’s goals and those of the Ethiopian government. The latter regarded international humanitarian organisations’ aid to the inhabitants of ONLF-controlled areas as potential support for the rebellion. Any contact with the insurgents—even though such contact was crucial to impartial distribution of aid and the safety of the humanitarian teams—was condemned as a sign of political partiality. This position was clearly expressed and defended during meetings with MSF representatives and in the official correspondence sent to them.Letter from Tekeda Alemu, Ethiopian minister of foreign affairs, to the heads of mission of the Belgian, Dutch, Swiss and Spanish sections of MSF, 18 Feb. 2008.

In 2009, the president of the Somali regional state even confided to a journalist that he believed “that MSF has a hidden agenda. MSF is consulting the ‘elders’ [clan chiefs] who have close relations with the ONLF, and hiring personnel who support the ONLF”. Peter Gill, Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia since Live Aid, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. MSF, convinced of the legitimacy of its cause of providing assistance to the Ogaden people, took a while to realise just how intransigent the government was. It tried to resist the pressure by playing on the fact that there were several MSF sections present and using the levers of diplomatic negotiation and public statement. But those public statements worked to its detriment. The September 2007 press conference referred to the accounts of violence logged by the Dutch section’s team, even though they had been regarded initially as insufficiently documented. This increased the Ethiopian authorities’ mistrust of MSF, who they accused of spreading propaganda on behalf of the ONLF under cover of providing humanitarian aid. A few weeks later, representatives of MSF were able to experience the government’s intolerance of criticism first-hand. During a meeting with the foreign affairs minister, they were shown a file of press cuttings containing all of MSF’s public criticisms of the government dating back to its denunciation of forced displacements during the famine of 1985.

In July 2008, the Swiss section’s public criticism of the government’s refusal to allow access to the area was weakened as the two other MSF sections were still in Ogaden and did not join in the accusation. A paradox that did not escape the notice of the authorities, who publicly accused MSF of “disseminating rumours whose content is clearly at odds with the reality on the ground”. “Ethiopia Slams Swiss Charity over Ogaden Pull-out”, Reuters, 12 July 2008.

When it came to negotiating with the authorities, even the heads of mission acknowledged that MSF’s network of official contacts in Ethiopia was insufficient and poorly organised. The operational teams, often with little experience in the country, struggled to identify the right contacts within a complex governmental system with blurred levels of responsibility; decisions on authorisations and restrictions were taken sometimes at regional level and sometimes at federal level, sometimes by the health authorities and sometimes by the army, without any clearly defined rules.

On the diplomatic front, the team responsible for coordinating the different MSF sections’ relations with countries, civil society and international institutions saw that appealing to the African Union would be futile, given Ethiopia’s prominent role in the organisation. The team therefore concentrated its efforts on United Nations agencies and western donors who, as providers of aid to Ethiopia, were liable to take seriously the difficulties experienced by the people of Ogaden in gaining access to their aid. But Ethiopia is the United States’ main African ally and its partner in the “war on terror”, particularly in Somalia where the Ethiopian government plays a leading role in the combat against Islamist insurgents. See infra, “Somalia: Everything is open for negotiation”, pp. 77–106.

Most of the diplomats and representatives of those UN agencies present in Ethiopia privately expressed their alarm at the government’s refusal to allow access to the area and its misappropriation of aid. While many of them encouraged MSF to voice what they were thinking, none of them seemed to have either the means or the ambition to change the balance of power with the Ethiopian government, a past master in the art of controlling aid.

Over the course of these events, the Ethiopian authorities manoeuvred MSF into waltzing twice round the floor. The first time of the first round began when the Ethiopian government launched a crackdown and denied access to the area from April to November 2007. The second was marked by MSF’s diplomatic and public protests, and the third by a spurious opening-up in November, briefly imposed on the Ethiopian government after pressure from the United Nations.

In 2008, events speeded up in the second round. Access was refused for longer, the period of opening-up was no more than brief. The authorities engaged in virtually uninterrupted harassment, paralysing all action by the MSF teams.

If MSF resisted the first waltz, it subsequently bent to the tempo that permitted it to stay at the dance. Since what was to be to date its last public statement on the situation in Ogaden, the organisation has kept a low profile, hoping to improve its relations with the authorities and thereby gain wider access to the region. This strategy is designed to enable MSF to assist the inhabitants should the conflict intensify, but there is no reason to believe that the Ethiopian government will be any more willing to open up the area than it was in 2007 and 2008.

Translated from French by Neil Beschers

***

Yemen. A Low Profile

Michel-Olivier Lacharité

In 2004, an insurrection led by former member of parliament Hussein Al Houthi broke out in the northern Yemeni governorate of Saada. His supporters objected to the Yemeni government’s political rapprochement with the United States, and demanded the return of Zaydism— the school of Shi’a Islam whose imams ruled Yemen until 1962. Lasting from June 2004 to February 2010, the Saada War was characterised by periods of intense conflict interspersed with relative calm.

The French section of Médecins Sans Frontières conducted an initial exploratory mission in northern Yemen in July 2007, after the signing of a ceasefire a month earlier under the auspices of the government of Qatar. After four episodes of fighting, the government had failed to suppress the Houthist movement, which had failed to gain control of any territory. MSF’s objective was to improve access to secondary healthcare in the Saada region, which had few hospitals and was at risk of renewed hostilities with the predictable consequences (war wounded, population displacements, etc.). The organisation started working in Haydan hospital in September 2007, in Razeh hospital in December 2007, and in Al Talh hospital in April 2008. While all three hospitals were in government-held areas when MSF first arrived, they progressively came under Houthi control during the course of the war—Haydan in 2008, and Razeh and Al Talh in 2009.

There was very little media coverage of the Yemen conflict between 2004 and 2007. The lack of war images and reports was due to the Yemeni government’s extremely tight control over information, exercised through physical persecution of journalists and legal prosecution of the regime’s opponents.Patrice Chevalier, “The Yemeni Law and How to Use it Against Journalists”, http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/36/17/00/PDF/Chevalier_The_Yemen... — version 1, 16 Feb. 2009.

These prosecutions stepped up in 2001, helped by Yemeni involvement in the “global war on terror”, which signified its alignment with the United States.Chevalier, “The Yemeni Law”, http://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/36/17/00/PDF/Chevalier_The_Yemen... — version 1.

The government also controlled the communications of the supporters of Al Houthi’s movement. Journalists close to the government created a think tank and a website, http://www.nashwannews.com. See Samy Dorlian, “Yémen: observation sur le traitement médiatique de la guerre de Saada”, Olfa Lamloum (ed.), Médias et islamisme, Beirut: Presses de l’Ifpo, 2010, Coll. Études contemporaines. the analyses of which were aimed at limiting the rebels’ capacity for political mobilisation, leaving them with almost no way to get attention, aside from pamphlets distributed to the population and rare contacts with the few journalists who dared cover the conflict.

However, by the time MSF launched its project in September 2007, the situation had evolved over the previous months. Qatar’s diplomatic intervention had brought media attention to the conflict—notably by Qatari satellite channel Al Jazeera. The insurgents began distributing DVDs with footage of the war, their military victories and speeches by their leaders, and posted information via electronic mailing lists, allowing them to circumvent the pro-Houthi websites that had been taken down.

MSF was the only international aid organisation to reach the combat zones, aside from the ICRC, which was acting through the Yemeni Red Crescent. One of the few foreign witnesses to the conflict and its disastrous consequences for the population, the organisation faced a dilemma; should it help expose the violence of this little-known war, at the risk of jeopardising its work? Between 2007 and 2009, the shifting context of intervention prompted MSF to choose caution. Its room for manoeuvre depended largely on the goodwill of the government, which required that travel by international staff, drugs and MSF supplies all be approved on a case-by-case basis by the Ministry of Planning, the police, and the governor of Saada. In 2009, MSF deliberately limited its communications to only making its activities in Yemen known locally—in other words, to gaining acceptance from the parties to the conflict.

A Convenient Silence?

Between August 2009 and February 2010, the town of Al Talh came under Houthist control and the hospital where MSF was working found itself on a frontline that advanced and retreated between Al Talh and Saada city. It was hit by bullets and shell fragments on several occasions in August and September.

On 8 September 2009, the MSF hospital teams treated seven children and one woman wounded by the air strikes that hit the centre of the town. Only two of them survived their injuries. On 14 September government planes bombed Al Talh market: thirty-one wounded and nine dead were brought to the hospital. Within moments, Houthist supporters burst in, en masse, to take pictures of the wounded, until MSF teams convinced them to leave by pointing out that the presence of insurgents made the hospital a potential military target. The governmental authority in the region contacted the project coordinator several times that day, assuring her that it had not given the order to bomb, and anxious to know whether MSF was going to say anything publicly about the event. The next day, the central authorities issued a press release in which they denied any responsibilityYemen National Information Center, http://www.yemen-nic.info/news/detail.php?ID=23227. Cited in “All Quiet on the Northern Front?”, New York: Human Rights Watch, Mar. 2010, p. 29. for the air strikes. Two days later, a government plane dropped pamphlets giving the population two options: fight the rebels or leave town.

In the days that followed, the fighting around Saada intensified. MSF teams worried about the impact of the growing insecurity on their ability to continue their work at the hospital. The evacuation routes toward the capital and Saudi Arabia were becoming increasingly dangerous, and the possibility of evacuating the international staff seemed less likely with each passing day. Members of the national staff, who travelled the road between Saada and Al Talh several times a week, were being stopped and harassed by the army, and prevented from moving around. Contacted by MSF in the hopes of obtaining assurances of safety, a high-ranking Yemeni military official advised the organisation to leave. On 22 September, MSF suspended its surgical programmes and arranged to transfer patients to the Saada hospital, about fifteen kilometres away. A few days later the expatriate staff were evacuated from Al Talh, and the national staff left the hospital.

The organisation said nothing publicly about the air strikes it had witnessed, thus failing to honour the commitment that had been made by the MSF movement as a whole in 2006: “We have learned to be cautious in our actions […] without precluding MSF from denouncing grave and ignored crimes such as the bombing of civilians, attacks on hospitals and diversion of humanitarian aid. Taking a stand in reaction to such situations and confronting others with their responsibilities remains an essential role of MSF”.MSF, La Mancha Agreement, Athens, 2006.

How did MSF justify remaining silent about a serious crime that few direct witnesses relayed to the outside world?

Operational managers at MSF felt that condemning the air strikes would amount to placing blame squarely on the government, and would jeopardise MSF activities in Yemen with little clear benefit. Would speaking out about civilian deaths in the fighting prompt the combatants to show restraint in their use of violence?

More generally, in 2009, MSF was expelled from Darfur, its activities in Niger were suspended by the government and, at the time of the air strikes in Al Talh, a public statement by MSF on internment conditions for people displaced by the Sri Lankan conflict had angered the authorities there. The perceived trade-off between speech and action was being hotly debated within MSF, with some managers demanding that the organisation just keep quiet and deliver care. During an Al Jazeera interview several months earlier in the wake of the Darfur expulsion, MSF’s operations director had stated: “You have to be able to distinguish between human rights and international justice activists and relief organisations”.

MSF had little desire to risk its entire Yemen operation by denouncing a crime that didn’t affect it directly; nor did it want to demand publicly that the warring parties spare the hospital and guarantee the safety of its teams and their freedom of movement. As the fighting intensified, the teams decided to move the staff and patients to safety and evacuate the facility, saying nothing, seeing no immediate tangible benefit to speaking out. On 5 October, however, once the few caregivers who had stayed to receive patients after MSF’s departure had all left the hospital, MSF issued a statement to the national press agency and several Yemeni newspapers. Hoping to be able to relaunch its activities in Al Talh someday and fearing the hospital would be looted and bombed, it “called for respect for [Saada governorate] healthcare facilities and their purpose”—in this case, for the deserted building itself and the equipment.

Idle Words

Every year MSF compiled and published its “Top Ten Humanitarian Crises”, a public relations effort aimed at increasing its visibility in the media. December 2009 was no exception and Yemen was on the list.

In particular, MSF said that, “Violence escalated sharply in August as Yemeni army forces began carrying out air strikes and artillery assaults against Al Houthi rebels”, and reported that “tens of thousands [of civilians fled] into neighbouring Hajja, Amran, and Al Jawf governorates, where they had little to no access to healthcare services”.

The information was picked up by Al Jazeera and many other Arab media outlets. The Qatari satellite channel even ran a special edition on MSF’s statements on Yemen in December 2009, its analysts wondering publicly about the negative impact this speaking out would have on the credibility of President Saleh.

The government’s response was instantaneous. Right in the middle of the war, it immediately suspended authorisation for all of the organisation’s activities in Yemen—the movement of people and vehicles, imports, new projects, and the renewal of MSF’s framework agreement. In a meeting, government representatives laid out their main grievances to the head of mission: MSF had failed to remain neutral in the conflict by only condemning military violence and not that committed by the Houthists, and it had offered an unfounded evaluation of the healthcare services in government areas where it worked little, if at all. One of MSF’s government contacts concluded, “It was this kind of purely political report that got you expelled from Darfur”. MSF internal report, Dec. 2009.

Yet listing Yemen as one of the Top Ten Humanitarian Crises served no clear political or operational objective—other than “to attract media attention to a neglected crisis”.Interview with deputy director of communications, MSF-France, Jan. 2011.

That lack of intention and objective resulted in a vague description of the conflict and its consequences in which the government may have seen a kind of empathy with the insurgents’ cause. And the brief account did present the government as the main culprit in escalating hostilities and impeding aid, cracking down on an uprising “claiming social, economic, political, and religious marginalisation”.

The authorities were explicit regarding the terms of the negotiation: if MSF agreed to deny that the Yemeni government was creating problems of access and that there was a lack of healthcare services in government zones, and to stress that the media’s sole use of the Yemen case out of the Top Ten report reflected that same media’s viewpoint only, the government would lift the sanctions. MSF accepted the deal. In December 2009, MSF operational managers sent the Yemeni government a letter acknowledging that the report may have appeared biased, and that the issues with civilian access to healthcare services were not sufficiently documented. The national press agency issued two press releases with headlines that spoke for themselves: “MSF apologizes for ‘inaccurate’ report on Saada”, and “MSF: apology to Yemen for wrong report on the health conditions of IDPs”. These were texted to a number of Yemeni mobile phone subscribers and picked up by about twenty national media organisations and a few international news agencies. The government immediately lifted all sanctions against MSF.

When Al Talh was being shelled, MSF saw speaking out publicly as a threat to its operations, rather than as a way to pressure the government to guarantee the safety of civilians and aid teams. It would have been difficult for the government to challenge immediate and first-hand testimony by a medical organisation treating the civilian victims of the air strikes, and itself affected by the lack of safety. But the Top Ten episode—which proved how sensitive the Yemeni government was about its media image during the war—showed how vulnerable MSF can be when it speaks out without a clear political or operational objective. At that point, the association had nothing to bring to the showdown with the national authorities. It had given the government fodder for its propaganda by denying that there were problems with access to care—problems for which both the government and the rebels were to blame.

Translated from French by Nina Friedman

***

Afghanistan. Regaining Leverage

Xavier Crombé (with Michiel Hofman)

On 28 July 2004, two representatives of MSF held a press conference in Kabul to announce the organisation’s decision to pull out of Afghanistan. They explained that on 2 June five MSF aid workers had been assassinated in Badghis province and, almost two months on, the Afghan authorities in Kabul had made no attempt to arrest and prosecute the identified suspects. In addition, an alleged Taliban spokesman had claimed responsibility for the killings and justified further attacks by accusing MSF of “spying for the Americans”. These facts had led the agency to conclude that “independent humanitarian action, which involves unarmed aid workers going into areas of conflict to provide aid, has become impossible” in Afghanistan.

Although these were the main reasons for the withdrawal, the MSF spokespersons also made clear that the international forces had to share the blame for the deleterious context in which those recent events had taken place. The US-led Coalition’s systematic attempts to co-opt humanitarian aid and use it to “win hearts and minds”, they claimed, had seriously compromised humanitarian aid workers’ image of neutrality and impartiality. MSF press release, “After 24 Years of Independent Aid to the Afghan People, Doctors Without Borders Withdraws from Afghanistan Following Killings, Threats, and Insecurity”, 28 July 2004.

To many of those attending the press conference and who recalled MSF’s twenty-four years of presence in Afghanistan—including through some of the worst times the country had known—the decision came as a surprise. “Aren’t there ways for you to stay […] and deal with the security situation?” someone in the audience asked.Transcript of the press conference, July 2004, MSF archives.

In an article published in The Wall Street Journal a few weeks later, Cheryl Benard, an American scholar close to the Bush administration, had a ready solution to offer: It’s a different world out there […] The principle championed by Doctors Without Borders—that civilian professionals providing medical help to the suffering will be granted safe passage—is now part of our nostalgic past […] An objective assessment of the facts would lead organizations like Doctors Without Borders to demand more military presence, not less; closer cooperation with the military, not a separation of spheres. Alternatively, they will have to withdraw not just from Afghanistan, but also from most of the conflicts of the 21st century.Cheryl Benard, “Afghanistan Without Doctors”, The Wall Street Journal, 12 Aug. 2004. Cheryl Benard’s husband was then the US ambassador to Afghanistan.

“In the ‘war against terror’, all factions want us to choose sides”, the president of the International Council of MSF fired back. “Ms. Benard’s ‘objective assessment’ […] is merely another example of this logic. We refuse to choose sides”. Dr Rowan Gillies, “The Real Reasons MSF left Afghanistan”, letter to the editor, The Wall Street Journal, 19 Aug. 2004.

The controversy was not new. It had been raging ever since the Bush administration had launched Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan in retaliation for the September 11 attacks on American soil and had called on humanitarian NGOs to join in the war effort. Yet, in the months that preceded the killing of its personnel, MSF found itself in an ambivalent position where the western forces and Afghan authorities it wanted to distance itself from were, in effect, its main interlocutors. While opting out of the reconstruction plan designed by an “international community” in open support of the Karzai government, MSF had had no contact with the armed opposition since the fall of the Taliban regime and had considerably reduced its programmes, including in those areas where the insurgency was reportedly gaining ground. The legitimacy that many at MSF felt they deserved, given the organisation’s twenty years of history in Afghanistan, was not enough to secure respect for a “humanitarian exception” increasingly at odds with the agenda of the main political, military and aid players on the Afghan scene.