Jean-Hervé Bradol & Jean-Hervé Jézéquel

Medical doctor, specialized in tropical medicine, emergency medicine and epidemiology. In 1989 he went on mission with Médecins sans Frontières for the first time, and undertook long-term missions in Uganda, Somalia and Thailand. He returned to the Paris headquarters in 1994 as a programs director. Between 1996 and 1998, he served as the director of communications, and later as director of operations until May 2000 when he was elected president of the French section of Médecins sans Frontières. He was re-elected in May 2003 and in May 2006. From 2000 to 2008, he was a member of the International Council of MSF and a member of the Board of MSF USA. He is the co-editor of "Medical innovations in humanitarian situations" (MSF, 2009) and Humanitarian Aid, Genocide and Mass Killings: Médecins Sans Frontiéres, The Rwandan Experience, 1982–97 (Manchester University Press, 2017).

Deputy Project Director for West Africa at International Crisis Group.

Jean-Hervé Jézéquel first worked as a Consultant for Crisis Group in Guinea in 2003, before joining as the Senior Analyst for the Sahel region in March 2013. He has also worked as a Field Coordinator in Liberia, a West Africa Researcher and a Research Director, for Médecins sans Frontières.

PART1 CRASH seminar: can malnutrition be solved by humanitarian medicine?

On 11 March 2009, the Centre de réflexion sur l’action et les savoirs humanitaires (CRASH) organised a seminar on the role of nutrition in medical humanitarian activity. After three years of increased treatment and lobbying, the response to undernutrition has reached another crossroads and things have changed greatly in recent years with new players, new products and new financing. These changes, which MSF helped instigate, led us to hold this seminar to consider the role that the association could still play in this sector of humanitarian aid. It seemed necessary to take stock of what we have learned from our operational experience and review our choices for the future: on which situations of nutritional insecurity do we wish to focus and with what objectives? How can our knowledge and medical techniques help deal with a problem that has important economic, social and political implications? How should we adjust our objectives and operations in contexts where aid providers and governments now have a more active presence than in the past?

The seminar was organised around the following three topics: situations; the state of knowledge and medical techniques; and the interplay of players and formulation of new policies. The aim was to update the various points of view on nutrition within MSF and to debate the options open to us today. The debate was also intended to lay the groundwork for changes in our operational procedures and policies.

The seminar consisted of three two-hour panel sessions, introduced by two short presentations and followed by an open debate. The following pages transcribe most of the discussions at the seminar of 11 March 2009.

Jean-Hervé Bradol et Jean-Hervé Jézéquel

1ST SESSION: “SITUATIONS”

Millions of undernourished people reappear every year in very different contexts: refugee or displaced person camps, major cities and rural areas, parts of the Sahel or the Indian sub-continent, prisons, orphanages, etc. How should we address this problem? In other words, how should we “screen” patients? On which situations does MSF wish to focus and with what objectives? Should we be looking for fertile ground for operational research, or should we focus on the “rejection fronts” that have not benefited from the major changes seen in recent years? Should we try to tackle malnutrition and infant mortality in shantytowns or in rural areas? Should we give priority to exceptional situations, or establish ourselves in areas where high malnutrition rates are frequent or even the norm? The discussions of the first panel session concern MSF’s own knowledge and conceptions of these situations: what we know also determines what we intend to do about them. And what do we know today about these malnutrition hotspots, and more generally about high child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia? What is the history of these hotspots? What causes the imbalances affecting them? What systems are in place to treat the consequences of food shortages and undernutrition?

PRESENTATION BY JEAN-HERVÉ JÉZÉQUEL, RESEARCH DIRECTOR, CRASH, PARIS

The first panel session of the seminar explores malnutrition “situations”. The aim was to discuss a few issues that MSF wishes to consider in operational terms: what are we facing when we speak of malnutrition? How should we tackle the problem, and to begin with, what should be the geographical entry points?

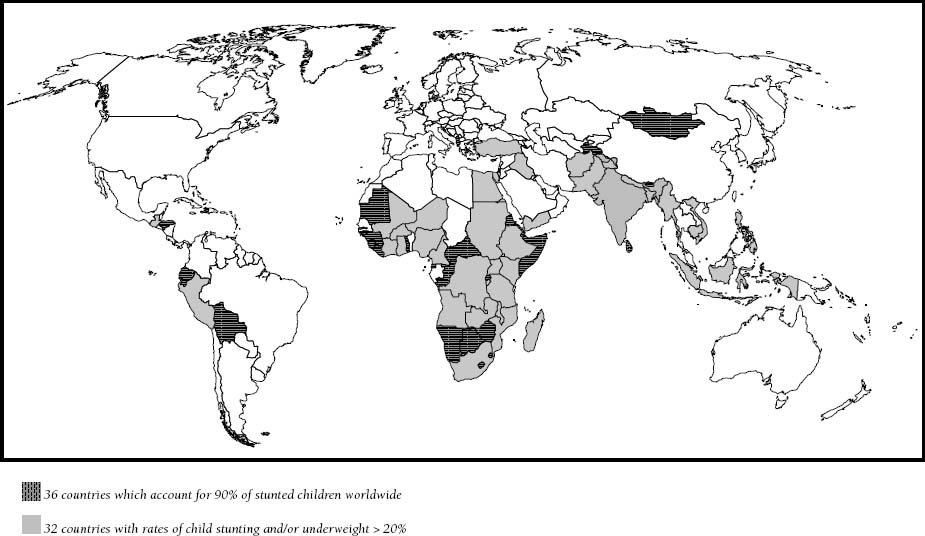

My starting point is one of the many maps that we use to get an idea of the scale of the nutritional problem worldwide. It is a planisphere showing the prevalence of underweight status round the world (see map below). The map shows high concentrations in the Sahel region of Africa, East Africa, Central Africa and South Asia. The first impression on looking at the map is that of malnutrition on a dramatic scale; all the green spots imply a “pandemic” requiring emergency measures. But where should we start?

I feel that this map raises more questions than it answers. Maps are not a true reflection of reality; they are constructions that direct one’s attention in a particular way and shed light on some phenomena and leave others in shadow. This map, for example, makes no distinction between very different situations, putting them all indiscriminately in areas of the same colour. In fact, using the vague concept of “hotspots”, this map lumps together arid, desert-like areas of the Sahel with green, fertile regions in southern Ethiopia; areas that are entirely rural or have low population density with the major conurbations and population centres of the South; areas at war or at risk of conflict with countries at peace. Clearly, malnutrition is not a result of the same conditions in all these areas, although in strictly quantitative terms it affects an identical proportion of the population. This map shows a worrying global situation, a sort of pandemic, but others could very well suggest, on the contrary, that these malnutrition situations are unconnected, that they reflect very different contexts that can hardly be addressed in the same way. So underlying the choice of cartographic representation is a hidden question on the nature of the nutritional problem: are we facing a single problem that calls for a general and relatively standardised response? If so, what role could MSF play in dealing with this problem? Or are we faced with a series of different situations that can more usefully be addressed separately than together? In my view, what is true for cartographers is also true for MSF. The way we are currently striving to grasp the scale of the problem is in itself the result of certain conceptions of the nutritional problem and even of the degree of responsibility we wish to assume for addressing it. This is not in itself a bad thing; it is normal to view “reality” through lenses that we ourselves have chosen. However, I think it important for MSF to be clearly aware of the nature of the “lenses” it is using today and the type of distortions that they may cause.

MAP OF UNDERNUTRITION WORLD BANK COSTING REPORT

How we see the nutritional problem partly determines the operational choices that we are making today. In our recent operational decisions, our ambitions for comprehensive treatment of malnutrition outweigh our assessment of the health status of a given population. The fact is that we are choosing our areas of operation by virtue of their potential for experimentation with new approaches related to early treatment or prevention of malnutrition. If Mali attracts more interest than northern Nigeria, it is not because the health situation is worse there or the absence of aid providers more flagrant, but because there seems to be much more opportunity to collaborate with governments in devising new ways of managing malnutrition. Once again, this is not necessarily a problem, but it is helpful to recognise what really influences our operational decisions. In this case, they are related to a particular view of malnutrition as a global issue: our local operations serve as arguments in a series of negotiations over global food and nutrition policies.

The map I am using as the starting point for this line of thought also says nothing about the players and systems being established in the fight against malnutrition. I think it is very important today to gain a better understanding of what others are doing, in order not only to emerge from our arrogant isolationism but also to grasp what has changed in the nutrition scene in recent years. MSF likes to see itself as the NGO that goes where others do not, which means precisely that we need to know where the others go. If we take seriously what is now merely a slogan for publicity purposes, we have two possibilities. We can go where the others do not in geographical terms, or we can do what the others do not in terms of types of operation, i.e. place ourselves in the forefront of operational research. I would therefore like to substitute for this map another representation that would take account of two types of situations that we face: first, what I call “rejection fronts”, that is, countries where very little has changed in terms of malnutrition treatment in recent years – for example, northern Nigeria – and second, “pioneering fronts”, namely areas where there have been noteworthy developments in recent years and where new treatment models have been introduced. Here, I am thinking in particular of Ethiopia, which has perhaps the most modern system of malnutrition management today, but also of countries in the Sahel, such as Niger and Burkina Faso, where both aid providers and local institutions are changing. Should we focus our efforts on the “rejection fronts” where fewer humanitarian players are present, where little has changed and the people do not yet have access to curative treatments? Or should we focus on “pioneer fronts” to take the lead in and accelerate the process of change?

There is another reason why we should take an interest in what other humanitarian players are doing in these “malnutrition situations” that we are trying to localise and address. We are not the only organisation taking an interest in the treatment of malnutrition today. We are only one of many groups of experts working on the case of the malnourished child. More specifically, we represent the medical expert, and as such, we do not have the same ability or legitimacy to treat the various forms of malnutrition found in the situations we see today. It seems to me that our work in Niger in 2005 marked the return of doctors in the management of malnutrition. We made the difference because we were treating a highly specific form of malnutrition, namely severe acute malnutrition, which is associated with a high fatality rate. When death is imminent, doctors are undeniably more effective and seem better equipped than other experts (educators, development experts or economists). But when we look at other forms of malnutrition, which are not severe but moderate, not the malnutrition we see today but that of tomorrow – since we are also speaking of prevention – it seems to me that we lose some of this comparative advantage. Other experts – educators, development specialists, public policy experts – also propose solutions. What is the position of the medical expert with respect to these other experts when the issue is no longer that of treating a form of malnutrition associated with a high rate of fatality and imminent death? These are the questions that I think should be raised in this first panel session.

PRESENTATION BY MICHELO LACHARITÉ, PROGRAMME MANAGER, MSF PARIS

I will try to answer the questions raised by Jean-Hervé Jézéquel, or at least to provide some clarification. How does the effectiveness and legitimacy of MSF actions vary with the contexts in which we operate? What is our relative advantage, our “value added”, in each of these contexts? In particular, what about the opposition between the role of medical practitioner and that of an influencer of policy? Lastly, what is MSF’s internal decision-making process in choosing the locations for our operations?

Before addressing these questions, I think it important to distinguish between the two main types of context in which we work to address malnutrition-related medical needs. First, there are situations marked by periods of crisis: war, famine, population displacement, and particularly serious hunger gaps, etc. In this case, the indicators that determine the decision to intervene are the crude mortality rates and severe acute malnutrition. In these contexts, there is generally a consensus within MSF to take action, although there may be some debate over how serious the situation is and how we should respond to it. There is no unanimity within MSF about the alert threshold that should determine when we should launch an operation. For example, at Akuem (southern Sudan) in 2005, the teams of the French section of MSF all had the same indicators, but could not agree on how to describe the situation or whether early intervention was appropriate.

Second, there are situations that I would call structural, in which malnutrition is not associated with a sudden crisis that is visible to international players and the local population. Examples include Burkina Faso, Mali, Ethiopia and India (this list is not exhaustive, but merely mentions the countries in which MSF France is currently involved). The indicators used to assess these situations are overall rates of chronic malnutrition and acute malnutrition, infant and child mortality and associated forms of morbidity. In areas characterised by endemic malnutrition, epidemic peaks (malaria, meningitis, measles, etc.) occur over the course of the year, especially during the hunger gap. These factors of morbidity combine to cause a high mortality rate, reaching levels comparable to those observed in crisis and conflict areas. There is one difference: these cycles of “excess mortality” are seasonal, recurrent and predictable. And yet, in contrast to contexts of crisis or social breakdown, there is no consensus within MSF for intervention in these contexts of endemic malnutrition.

Most of our current debates are concerned with these structural situations. Can we intervene in these contexts with the same effectiveness and legitimacy as in contexts of crisis? The recent development of new operational methods has, in my opinion, opened up new prospects for MSF. An example is the management of severe acute malnutrition patients as outpatients thanks to the use of ready-to-use therapeutic foods. Another is early treatment of malnutrition and associated diseases using ready-to-use food (RUFs) and the associated care packages. These new operational modes enable us today to have a significant impact on hotspots of mortality. Previously, we could not hope to have such an impact, owing to the lack of adequate strategies and operational methods. With recovery rates close to 90% in outpatient management of severe acute cases, we are achieving excellent results that are undeniable proof of effectiveness.

We are wasting a great deal of energy today by trying to evaluate “scientifically” the effectiveness of new products (in this case, RUFs), as if we could put our patients under a bell jar and isolate them from the other parameters of the context. After all, it is the responsibility of the manufacturer or of nutritionists to evaluate the effectiveness of a new product; ours is to assess the impact of our operations relative to the needs identified initially. In my opinion, MSF should focus on the overall impact of an operation, that is, on the care packages provided by our teams. But the fact is that our teams rarely limit their activity to the treatment of malnutrition or distribution of RUFs. For example, outpatient treatment of malnutrition often includes prophylactic care (vaccination, antibiotic treatment and parasite elimination) and treatment of associated pathologies. Similarly, in the case of early treatment using Plumpy’doz, we also try to prevent the main associated pathologies through better vaccination or mass parasite elimination, systematically combined with the detection of diseased children within a cohort and their referral to medical facilities. For example, in Mali, we want to combine distribution of therapeutic foods with prophylactic measures against malaria. We should therefore be speaking in terms of the package of MSF activities in early childhood care, rather than solely of treatment of malnutrition. And it seems to me that, in our most recent operations, MSF has shown an undeniable effectiveness in this respect.

Jean-Hervé Jézéquel raised the question of the legitimacy of our operations: “We represent the medical expert, and I think that the medical expert does not have the same ability or legitimacy to treat all forms of malnutrition depending on the types.” Legitimacy is founded in law, but I do not think that Jean-Hervé meant that type of legitimacy. He was probably referring to the subjective view that one may have when faced with a given situation. Indeed, it is more legitimate for a doctor to treat a wounded person than a plumber. Yet few players outside MSF question the legitimacy of our interest in early treatment of malnutrition. When people within MSF refer to the concept of legitimacy, it seems to me that they are speaking in ontological terms. They define the pseudo-essence of MSF, and if a given activity does not correspond to that essence, it is deemed to be illegitimate. In my view, MSF no more has an essence than it has a specific mandate. Our missions change with the contexts and the tools available to us. We are free to engage in new medical activities and to include them in our social mission, particularly if they are of proven effectiveness.

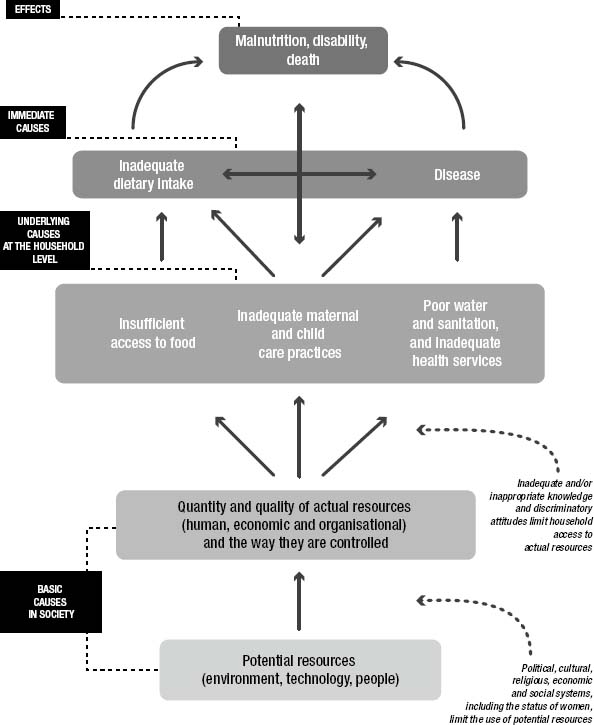

Let us use UNICEF’s causal schema of malnutrition, which defines infectious disease and inadequate diet as the two direct causes of malnutrition and mortality. In all of our operations, we address both the effect (malnutrition) and the two direct causes of malnutrition (infectious disease and inadequate diet). Restricting our activities to diseased persons and cases of several acute malnutrition - i.e. to patients who have reached the stage that precedes death - should be more problematical for us when the incidence of severe acute malnutrition is very high, when there is a high rate of chronic malnutrition and when the mortality rate is also high. Is it not possible to provide early treatment? In some situations, instead of waiting until we need to treat a large number of cases of disease or severe acute malnutrition, we have other solutions available. We can distribute ready-to-use food supplements (RUFs) to improve the quality of the subjects’ diet. We can also administer prophylaxis, eliminate parasites and/or supplement vaccination coverage, depending on which forms of morbidity are the most lethal. Let’s consider a different pathology: malaria. We let others handle the marsh-draining campaigns, although these are quite effective in checking malaria in endemic areas, so as to concentrate our efforts on screening and treatment based on appropriate products. This should also be true of nutrition. If malnutrition is multi-causal and we leave it up to development specialists, farmers or other experts to tackle the roots of the problem, it seems to me legitimate for MSF to concern itself with the effects and immediate causes.

What then is MSF’s comparative advantage? Jean-Hervé Jézéquel seemed to oppose cases of Nigeria and Ethiopia to that of Mali. To oversimplify, this amounts to saying that we take no action in Nigeria out of negligence or laziness, despite a very bad nutritional situation, and that we do intervene in Mali for reasons of facility and opportunism, because there are donors present and the government is friendly. I think that this is a mistaken analysis. The teams in Nigeria had started some nutrition-related activities in Katsina in 2005, and we tried to return there in 2006. However, we met with a categorical refusal on the part of the authorities. Last year, we went back to the area to work on measles, and once again we met with a veto on anything related to nutrition. I do not think that we ignore worrying hotspots or that we refuse to address them. However, I think it might be better to develop other operational modes for use in these “rejection fronts”, notably by seeking alliances with Nigerian civil society organisations, which are more discreet, better integrated and hence better suited to try to break through such fronts. When one child in four does not reach the age of five, and where there is a high rate of severe acute malnutrition, and only 40% of diseased people have access to real health services, has the situation not reached a level that justifies our intervention? This is the situation in Mali, where it seems to me legitimate for MSF to intervene. I think that the experience in Niger demonstrates that there is a role for doctors in the nutrition field, especially when we have the tools needed to address the situation and the right conditions exist – including political opportunities and prospects for funding – for some hope that the operation will have a real impact.

The operations department has chosen to work in the two broad types of context defined above: “classical” nutritional emergencies (where they work mostly independently of governments) and hotspots of “structural” malnutrition and high mortality (where the operations department wants to develop real medical and political partnerships with governments). How then should we decide where to mount operations? It is important not to compare situations on an a priori basis, taken out of context, and eliminate some of them from our “legitimate scope of action”. I think we should assess our ability to respond to identified needs, our effectiveness and our efficiency with respect to a given context. In 2008, the French section of MSF received 47,000 children for outpatient treatment of malnutrition and 9,000 for inpatient treatment. UNICEF estimates that 150 million children are affected by malnutrition, so clearly much remains to be done. Our goal is not to treat all of them, but neither can we stop where we are because of the efforts already made. In 2009, the funding that the Paris MSF group allocated to nutrition accounted for less than 5% of the “missions” budget.€5.7 million out of a total budget of €111 million -July 2009Although nutrition remains a priority for MSF, the resources currently allocated to it do not seem disproportionate. Budgetary reasons should thus not be an insurmountable obstacle to the initiation of new projects. Nonetheless, choices will have to be made between the various possible locations for MSF action in this field. I am not sure that we are specific and explicit enough concerning our objectives to make these choices in a calm, reasoned manner. It is essential to clarify our strategies if we want our projects to complement one another and to broaden the range of possible strategies.

SUMMARY OF THE ENSUING DISCUSSION

Fabrice Weissman (research director, CRASH) called for a critical look at general maps and macro-data on malnutrition. They tend to equate health situations that actually belong to very different social and political contexts. Regarding nutrition, as indeed for everything else, he thinks that our choice of operations should primarily be guided by a political analysis of the conditions under which we could work in the areas concerned.

Stéphane Doyon (CAME) pointed out that humanitarian organisations have acquired the reflex of treating malnutrition in emergency and/or conflict situations, but are more reluctant to conduct operations in countries at peace. Data from surveys conducted in some of these countries show that they have very high malnutrition prevalence rates, and that malnutrition remains a neglected disease. Even recently, malnutrition in these areas was seen more as a development problem than a medical issue. With the new treatments available, we have been able to provide a mass curative approach and make malnutrition a medical issue once again in areas of high endemicity. But we still face the problem of chronicity: treatment operations are certainly effective, but they have to be repeated each year. They also give rise to a form of rationing, because only the children who have reached the most severe stage of malnutrition receive treatment. These observations, derived from our practice, are leading us to consider preventive approaches to the problems we are facing. It is true that this would take us from a purely medical logic to a more “food aid” logic. But in a certain sense, we would simply be carrying out more extensive food handouts, as we have done in war situations. Through our practice, we will show that operations combining new products with new operating procedures are much more effective than the inappropriate strategies used to date by other aid providers.

Rony Brauman (research director, CRASH) voiced the opinion that even if a problem recurs from year to year, this does not make medical intervention any less meaningful. This is as true for MSF as it is for doctors who primarily treat recurrent problems. This point is not trivial, when one sees how the argument that recurrent operations are of no medical use is gaining strength within MSF. Rony Brauman also thinks that the definition of malnutrition and its pathological nature should be clarified. The reason is that the definition of malnutrition does not amount simply to a matter of measurements and norms. Exploring the link between malnutrition episodes and increased mortality could help us to understand the problem better from a medical standpoint.

Concerning the problem of maps, Jean-Hervé Bradol (research director, CRASH) reminded participants that these are mostly politically-oriented maps related to the Millennium Development Goals. It would be naive for MSF to neglect the underlying political context of these maps. Jean-Hervé Bradol also thinks that classifying malnutrition situations by their causes (war, desertification, etc.) is not very helpful. The same holds true when situations are classified by type of malnutrition, because the various types are so intertwined. For MSF, it is ultimately more pertinent to consider the various types of situations in the light of our own know-how and the influence we can have. What is new since 2005 is that we have realised that our interventions have an impact not only on a series of individual cases but also on the epidemiological profile of an entire community. We feel this intuitively, and this intuition needs to be discussed and confirmed. However, we have a problem concerning measurement and evaluation tools. The impact of acute diseases is generally analysed in terms of incidence, whereas our main tool for monitoring acute malnutrition remains the prevalence survey.

On the question of what is measured and by what method, Vincent Brown (epidemiologist, MSF) pointed out to Jean-Hervé Bradol that MSF produces weekly data on incidence before it conducts prevalence surveys. He also thought that the centre of the nutrition debate does not lie in the question of what techniques and indicators are apt to demonstrate the efficiency of MSF nutrition projects. Geza Harczi (nutrition issues officer, MSF medical department) disagreed, saying that the lack of reliable data and a monitoring system is a vital problem, as these would help us to identify the areas where our intervention would be the most useful. So the malnutrition map presented at the beginning of the discussion has a certain value in that it indicates both the prevalence of underweight status and population density.

Philippe Levaillant (former head of MSF-France’s mission in Niger) replied to Rony Brauman saying that measuring malnutrition is not the same thing as defining it. For him, malnutrition is a “quantitative and qualitative diet deficiency in young children that makes them unable to resist the diseases they face as they grow up”. Responding to Jean-Hervé Jézéquel’s presentation, Philippe Levaillant noted that there is indeed renewed interest in malnutrition, but that few medical organisations are active in the field. He mentioned the classification used by Dr Steve Collins, who draws a distinction not between moderately and severely malnourished people, but between malnourished people with medical complications and those without complications. The point is that, apart from MSF, which has considerably improved its work in this field, few organisations have succeeded in treating malnourished patients with medical complications effectively. This may be where MSF, as a medical organisation, can best play a role in the overall response to malnutrition.

For Yves Martin-Prével (nutritionist and researcher, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement), malnutrition is a global issue that affects all countries, including the United States where malnutrition occurs through dietary excess more than dietary deficiency. In developed countries, however, governments have established systems of varying degrees of efficiency to deal with the problem. Elsewhere, there is little or nothing to deal with it. MSF should therefore consider whether it should participate in developing such systems, instead of limiting itself to the question of severe acute malnutrition alone.

Joan Tubau (programme manager, OCBA) recalled the conditions in which OCBA’s nutrition project in India was initiated. It was through its activities in India that OCBA discovered the malnutrition problem and decided to address it. Many other organisations were present, but none of them offered medical treatment for severe acute malnutrition. Contrary to what Jean-Hervé Jézéquel said, this project was not driven by a political agenda set by the organisations’ head offices. It started at the grassroots and was then discussed at the desk level. We still don’t know where it will lead, but we have to accept this element of trial-and-error and uncertainty. The main thing today is to be able to save the lives of these children.

Fred Meylan (emergencies manager, OCG) recalled the conditions in which the Djibouti nutrition project was initiated. He affirmed that MSF has been observing malnutrition problems for fifteen years, yet no section has sought to address this problem, probably because it seemed too structural. MSF-Switzerland finally decided to do so, although in his opinion geopolitical considerations did not play a determining role in the decision. Fred Meylan is favourable to Rony Brauman’s argument: resigning ourselves to carrying out repetitive tasks is also part of our job.

End of the first session

2ND SESSION: KNOWLEDGE AND TECHNIQUES

Is the anthropometric norm an objective we should strive to attain? What do we know about the relationship between deviation from the anthropometric norm and mortality? Is there a standard treatment? Should the standard treatment be the one that most often brings patients closer to anthropometric norms? With the new WHO norms, is there still any point in treating moderate acute malnutrition? Can a treatment be evaluated in the same way as a programme? Can there be scientific proof of the effectiveness of a given policy?

PRESENTATION BY GEZA HARCZI, NUTRITION OFFICER, MSF MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, PARIS.

Whom should we treat for undernutrition? The question of how to define malnutrition brings us to the commonly used anthropometric indicators. These indicators are simply one of several tools that serve to assess the nutritional status of an individual. We will review the various anthropometric indicators, in each case noting their correlations with the risk of mortality. Biological tests are ill-suited to our working conditions in the field, as well as being largely non-specific. Clinical examination still has an important role, whether in a routine paediatric consultation or a consultation that is part of a nutrition programme, particularly when the clinician tries to assess the severity of a child’s condition, which cannot be done through anthropometric indicators alone. The fact is that the indicator says nothing about the speed at which the child’s health is deteriorating, nor about the speed of wasting. A child having an initial weight close to the ideal norm can sustain substantial weight loss, e.g. 10% of body weight, as a result of an episode of diarrhoea, without necessarily crossing the anthropometric threshold below which he/she would receive treatment. Yet the speed and scale of the weight loss increase the child’s risk of death. In contrast, a child whose initial weight is already somewhat below the norm but not yet below the anthropometric threshold value will receive nutritional treatment following a minimal loss of weight that puts him/her below the limit, even though the child’s risk of dying has changed very little. This highlights the importance of regular monitoring of children’s development in order to know precisely when they need nutritional treatment. Mere anthropometric measurement of a deviation from an ideal norm cannot replace clinical monitoring. A complementary examination will be interpreted according to a context, in the light of a clinical process. The aim of nutrition management is not to have all children reach an ideal anthropometric norm. If there is one norm from which we would prefer not to see children deviate much, it is a physiological growth norm. Our aim is not to produce fat children, or tall children, but healthy children. The underlying principle is that dietary deficiencies cause major physiological disruptions, and anthropometrics reflect this very imperfectly. The sensitivity and specificity of anthropometric indicators could be discussed at length. Nevertheless, this tool helps us in diagnosis, when used as a complementary examination to be incorporated into the clinical approach.

The above remarks also hold true for individual treatment of malnutrition. But the other question concerning anthropometric indicators is exactly when a given situation requires specialised nutritional treatment owing to the severity of the undernutrition of a given population. Anthropometric tools, used for malnutrition prevalence surveys, are also factors in the decision on whether to launch a specialised operation with a group of individuals. The main objective in a situation that is already severe is to help reduce mortality. Some authors, notably David Pelletier,“Changes in Child Survival Are Strongly Associated with Changes in Malnutrition in Developing Countries”, David L. Pelletier and Edward A. Frongillo, 2003, American Society for Nutritional Sciences.who has done extensive work on the relationship between anthropometrics and mortality, have established that a significant reduction in mortality can be expected from a reduction in morbidity (primarily infections) and/or malnutrition. The maximum expected impact would be obtained by working on both aspects: morbidity and malnutrition. The other postulate is that resources are limited and that this must be taken into consideration. MSF’s Campaign on Access to Essential Drugs (CAME) has been advocating for years that not enough high-quality foods and food supplements are being produced to cover requirements. And even if enough of these were produced, would health organisations have the capacity to distribute these foods and administer treatment? Resources are limited so we must use them rationally. The decision depends on the expected benefit from an operation targeting an entire population. In a large population, if few treatments are available, they will only be used for the most severe cases. However, Pelletier’s work shows that the greatest impact on mortality would be obtained by addressing malnutrition at its various stages (not solely in severe cases), in the locations showing the highest rates of morbidity and malnutrition. This brings us back to the idea of “hotspots”, discussed in the first part of this seminar. Hotspots are areas with large, concentrated populations with high malnutrition prevalence rates. By working in such areas, one can hope to have a stronger impact on mortality. This does not, however, mean abandoning the aim of treating malnutrition through individual paediatric care.

Whom should we treat? The main results of 39 prevalence studies based on several indicators (weight/height, height/age and weight/age) show that it is crucial to address the problem between the ages of 6 months and 24-36 months. Degradation of anthropometric indicators often begins before 6 months of age and intensifies at the point when breastfeeding is no longer sufficient to meet all the needs of a growing child. The food supplements needed in this critical period are generally lacking in both quality and quantity in the contexts where we operate. A high density of calories and micro-nutrients is needed to meet the substantial physiological needs at this high-growth period, because an undernourished child has a small stomach and the density of the therapeutic food is crucial. It is usually said that nutritional status degrades at the age of 6 months. In fact, the process certainly begins before that age in most cases, but intervening at an earlier age is problematic as it may interfere with the principle of exclusive breastfeeding. Nutritional care takes on its full meaning as from 6 months of age.

Several indicators are used to study the relationship between anthropometric status and the risk of death (weight/height, mid-upper-arm circumference [MUAC], height/age), but none is a “gold standard”. The prevailing tendency in our professional circles is to give preference to the weight/height ratio, which we have grown accustomed to using for pragmatic reasons. However, this is not a reference to be compared with MUAC as regards sensitivity and specificity. No one indicator is predominant; each has advantages and disadvantages. In March 2007, the WHO and UNICEF called for reconsideration of the relevance of MUAC because, as the UN states, it is easy to use for community-level management of malnutrition. In addition, the threshold values used to define severe acute malnutrition (below -3 for the Z-score, below 70% of the median and below 110 millimetres for brachial circumference) all have limitations for establishing a precise prognosis. But the greater the deviation from the anthropometric norm, the greater the risk of death. When we used the NCHS charts, which were based on data for children living in the United States, two-thirds of all deaths due to acute malnutrition occurred in the group suffering from so-called moderate acute malnutrition. So in Niger in 2006, we wanted to extend the scope of care to include children who were classified as cases of moderate acute malnutrition but who were so numerous that the majority of undernutrition-related deaths occurred in this category. The WHO’s new charts, issued in 2007, changed this aspect of the situation, and comparison with the data we collected in Niger in 2006 shows that the United Nations’ new weight/height standard is more successful in classifying children with a high risk of dying in the category of severe acute malnutrition. In short, the “severe acute malnutrition” category now includes a larger number of individuals and a higher proportion of children whose lives are at risk.

But we cannot focus solely on children suffering from severe acute malnutrition (wasting), since stunting also carries an increased risk of mortality. A recent example illustrates this point: three or four weeks before our meeting, Andrea Minetti of Epicentre conducted a prevalence survey in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia. The survey found a mean Z-score below -2, and found that the distribution of this population was strongly shifted to the left (63% showed stunting, and 37% severe stunting). We can get an idea of the relative risk of death among these children from an observational study conducted by Wafaie W. Fawzi“A Prospective Study of Malnutrition in Relation to Child Mortality in the Sudan”, Wafaie W. Fawzi, M. Guillerino Herrera, Donna L. Spiegelman, Alawia El Amin, Penelope Nestel and Kainal A. Mohamed. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1997:65:1062-9who monitored a group of Sudanese children in the 1980s and 1990s, measuring them every 6 months for a period of 18 months, with no treatment. Fawzi’s work suggests that for 37% of the Ethiopian children examined by Andrea Minetti, the relative risk of dying within 18 months is at least 2 to 1. Overall, studies of mortality risk from childhood diseases show that this risk increases with the degree of undernutrition, whether the latter is measured by the weight/height ratio or height/age ratio. The decisions we must take are also influenced by the seasonal nature of food insecurity, which has been thoroughly documented by CARE in the northern Bar-El-Ghazal (Sudan), based on survey data from the 1998-2006 period. There is clearly a seasonal degradation during the hunger gap. The results of a nutrition survey should thus be interpreted according to the season during which the data were collected.

In situations that are already very bad, the data show that the entire population is undernourished. In crisis situations, the distribution curve of weight/height ratios within the child population shifts towards the left (undernutrition) and almost all individuals are affected to some extent. The mean is used to estimate the number of individuals lying outside the norm, at the extremities of the curve. Since almost all of the age group is undernourished, why do not all these children receive treatment? What is the rationale for selecting those who should receive food supplements? Such screening takes an enormous amount of energy, staff time and money. This led us to consider treating an entire age group (children from 6 to 36 months in the case of Guidam Roumji, Niger, 2007).

DISCUSSION OF GEZA HARCZI’S PRESENTATION

Rony Brauman, research director, CRASH

– Is the anthropometric norm used truly universal? If so, we need an explanation, because in practice, we see that physical profiles vary, and that the idea of a universal norm does not appear to be valid.

How do we use these norms in consultations to assign a child to one category or another, and decide what treatment to administer?

Susan Sheperd, Coordinator, MSF International Nutrition Working Group

– The new anthropometric norm stems from a study of a group of about 8,000 children in six countries on five continents (The WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study, 2005). They were all living in families with sufficient purchasing power to feed themselves adequately. The mothers were in good health, did not smoke and carried their pregnancies to term. The children were breast-fed, at least for the first four months. The principal differences with the previous norm (NCHS, based on children in the United States) relate to breast-feeding -which plays a much more important role - and the statistical approach. The previous norm represented the growth of a group of privileged children living in the United States, whereas today, an ideal growth norm is proposed. One of the WHO’s answers to questions about the universal nature of the new norm is to say that, in the six countries covered by the study, the variations within groups of children in a single country are greater than those between groups from one country to the next. Some human populations – such as the Dinka in southern Sudan, who have a very elongated body shape – have specific growth profiles. Does a pygmy child have the same weight at birth as a Dinka child, a Nigerian child or a Brazilian child? These new WHO standards are certainly an improvement over the growth charts produced in the United States in the 1970s. They are universal in the sense that they are the reference that everyone uses. Today, we are seeing the transition from one standard to the other, on an international scale.

Yves Martin Prével, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD)

– The new standard presents a growth potential that, as has been practically established, is the same for all children, regardless of their origins. Several types of research studies support this point of view. The average size of the Vietnamese who have emigrated to the United States has, in two generations, become identical to that of all Americans. The average size of a population depends on the environment, not on genetics.

Rony Brauman

– You mean that Americans are normal and that the Vietnamese are not normal until they arrive in the United States?

Yves Martin-Prével

– No, I did not say that. I say that, when placed in the same environment, Vietnamese and Americans have identical growth patterns. I did not say it was normal. Should we try to direct the human race towards an ideal weight and height? Is that reasonable? Isn’t that discouraging for the countries and populations that are furthest from that ideal? In response to the question about whether these norms are universal, I think that the Dinka (a very tall people in southern Sudan) and pygmies have different morphologies. But if pygmies spent three or four generations in a much more favourable environment for their growth, wouldn’t their growth pattern catch up to the current norm? The answer is probably yes, in the current state of our knowledge. The other type of reasoning that leads us to think that different populations have the same growth potential is based on historical comparison. The curve in Andrea Minetti’s Ethiopia study corresponds to the curve for poor people in England in 1840. What has changed in England? Presumably, it is not the genetics of the English people but rather their environment.

Rony Brauman

– The normative aspect of nutrition becomes apparent in the denial of normativeness. It is stated that the nutritional status of Ethiopia today is the same as that of England in 1840. This implies that Ethiopia is 160 years behind England. When we speak of the growth potential of the Vietnamese or Japanese who come to live in the United States and “catch up” to American height, it is because we think they were lagging behind.

The scale of intervention is defined in terms of these normative ideals. In other words, we are creating our own market for operations. We should also take into consideration the way some research scientists manufacture their own markets when judging the results of their research. We see numbers in the millions that are specified down to the last digit, when in France we only know the real situation of the French population to within 2 or 3 million. How can we even know how many people are living in the Sahelian countries? What denominator is used to calculate these proportions? In some cases, the population base on which morbidity and mortality were calculated varied by a factor of three, sometimes a factor of ten, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo. All of this is extremely unsound. Not only in philosophical terms (the universalising, normative aspect) but also in practical terms (accuracy of the calculation).

Jean-Hervé Bradol

– Geza Harczi’s presentation undeniably implies the promotion of a norm, with all its arbitrary, debatable aspect. This leads in practice to a ranking of populations. Of what practical use is this norm in our health care activities? Do we prescribe treatment with the goal of seeing all the children in a given population reach an ideal weight? No. In practice, what interests us is the size of the deviation from the ideal norm and its consequences, particularly the mortality rate associated with that deviation. In our practice, the norm is not an ideal that we strive to reach, but a guide from which we should not deviate too far. For this reason, analysis of the associated risks, particularly the risk of death, is of fundamental importance in defining our goals and evaluating our results.

Jean-François Etar, directeur scientifique, Epicentre

– I think we must consider the children’s individual characteristics, and we have methods that allow us to quantify the deviation from the overall mean. The problem is methodological. We would need to take several measurements per child and have a longitudinal compendium of measurements to capture the deviation from the average growth of the other children. Instead of giving results in the form of percentages of pre-defined norms, we need to have an idea of the individual variations of each child.

Jean-Hervé Jézéquel

– I have a question on the notion of associated risk, on the way in which two elements are associated and isolated: these elements are malnutrition and mortality. We isolate malnutrition on the one hand and mortality on the other, ignoring the rest of the environment. That reminds me of political science studies of confliction in Africa that show that the risk of conflict increases with the proportion of young people in the society. To have fewer wars, have fewer young people! The link established between two isolated factors disregards the context that connects them and that, if it were taken into consideration, could shed light on the meaning of this link. Do we establish the same link between malnutrition and mortality in a context where malaria is widespread and a context where it is less so?

Yves Martin-Prével

– I agree that what interests us is the deviation from the norm rather than trying to attain the norm. A population’s mean deviation from this norm has implications for the mortality rate of that population, for learning lags and for the country’s gross domestic product. How valid are the calculations? They have been subject to many debates and criticisms. Today, there are major controversies over the work of Pelletier. The questions have to do with the level of mortality associated with malnutrition: 54% or 35%, as is claimed in the latest series of The Lancet? In both cases, the mortality rate is much too high to be tolerable.

Rony Brauman

– A high rate of malnutrition or of mortality may seem morally untenable, but in order to assess it we must see it within an historical trend. For example, consider the figures that the demographer Alfred Sauvy used to show that the world was not so badly off after all. He showed that if nothing had changed, all other things being equal, the annual number of deaths would be not 50 million, but 120 million. Thus, dividing the theoretical mortality since the 1930s by 2.5 showed that a number of factors had considerably improved life expectancy. But who will say that 50 million deaths is good and 120 million is less good. The issue is obviously not to form a judgement in absolute terms, but to understand the broad trends. I think that the precision and accuracy of numbers are important, so that we can dispute them when they are produced for reasons other than understanding reality as it is. I do not see any conspiracy or ulterior motives here. In epidemiological terms, it can be demonstrated that research is influenced by many things, and in particular by those who sponsor the research.

Jean-Hervé Bradol

– It is interesting to note the internal context in which we are discussing the anthropometric norm. In our recent past, indicators of severe acute malnutrition were the only thing that triggered a field operation. The norm we used to work with was very severe, in every sense of the word. With the old curves, as we say in our jargon, two-thirds of malnutrition-related deaths were not covered in our objectives. It seems to me that we are now in a period when norms are used more flexibly. In practice, we now mount successful operations to help children who used to be excluded from receiving care. The predominant attitude in our professional circles is still not to intervene except in cases of severe acute malnutrition. This prevailing norm is an issue because we find it overly restrictive.

Apart from this question of the norm, another subject that concerns us and that crops up often in our internal discussions is the question of proof. That is, how do we prove something? Should we wait for scientists to provide proof that our field policies are the right ones? On this subject, I leave the floor to Rebecca Grays.

PRESENTATION BY REBECCA GRAYS, EPICENTRE

I will speak in English. We can speak French later on, but in a discussion like this one, words are very important. Jean-Hervé asked me to review these questions, and I will try to do so. The first thing I will talk about is the concept of proof in the scientific method.

And in particular, I will speak of proof, of the reproducibility of results, the role of publications and the reality of the scientific method; lastly, I will speak of the moment when studies should be conducted, how they should be conducted, and the implications for nutrition.

The first subject is proof. The English word “proof” can have different meanings from the French word preuve. Proof in English means “something established beyond doubt”; there are several types of such proofs. There is “real world” proof; for example, “she called me an idiot and here’s the e-mail that proves it”. There is mathematical proof, such as the Pythagorean theorem, made up of a set of rule-based affirmations that lead necessarily and absolutely to a set of conclusions. There is legal proof as well, which depends on the legal system to which one belongs. “Scientific proof” has a very specific definition. In fact, it is not proof at all! Scientific proof considers a set of peer-reviewed experiments, formulae or conclusions; the term “peer-reviewed” is very important here, and we will come back to it. A particular idea has every chance of being true as a result of a proof, and in this case, proof means a piece of information that supports or does not support a theory. In scientific proof, the objective is thus to try to predict as closely as possible what will happen in future situations. In other words, it is the best solution in our current state of knowledge. It is not a quest for truth, since knowledge is constantly changing and truth is relative; rather, it depends on the state of our knowledge.

So how is such proof established? If you remember from your studies, we used the scientific method to obtain a scientific proof. First, we observe what happens; and we formulate a hypothesis to explain it. Next, we evaluate that hypothesis through experiments: this is the second step. Third, we conduct experiments, and fourth, the proof obtained through these experiments should ideally be reproduced by other people. If the hypothesis agrees with the proof, it becomes a theory. If it does not, we go back to step 2, reformulate the hypothesis, and carry out the next steps again. When we obtain a theory, we are in a position to make predictions about the future. Today, I will speak primarily about steps 3 and 4. Many people prefer to deal with steps 1 and 2, and neglect steps 3 and 4!

In step 3, all the proofs are not equal. There are levels of proof, with a hierarchy. You see on this slide the system of levels used by various groups – government health departments, universities and the UN, among others. The randomised control trial (RCT) is the highest level of proof, the ideal being to have several RCTs and then to study their findings. The next level down is the non-randomised comparative trial. Next come group studies or case series, followed by time series, with or without intervention. The lowest level of proof is personal opinions. They are the opinions of experts, but sometimes it’s all we have.

Why are RCTs the highest level of proof? Why are they always so important? And why are they always put under the spotlight? RCTs consist in randomly selecting people or groups of people to form other groups, which then receive one or more interventions. They are comparative: one element is compared to another, or a number of elements may be compared. RCTs are experiments, that is, they are controlled by the person conducting them, and there are enough subjects participating to ensure that the known and unknown confusion factors (I will come back to this) are also divided between the groups. After the trial, if your experimental intervention shows a significantly different effect concerning the control group (the group to which we are comparing the factor studied), it is probable that it had an effect on the disease. That is what can be concluded from an RCT. This is the highest level of proof we have in decision-making.

Why is randomisation considered so important? For two reasons. The first is known as causalation, a portmanteau word made of “cause” and “correlation”, and the second is the confusion factor. The classic example is the extremely strong correlation between ice cream sales and shark attacks. First of all, we’re not going to think that sharks are eating us because we have been eating ice cream. If we arrive at that conclusion, we are guilty of causalation. And it is not true, because there is a confusion factor. And this confusion factor is either the heat or the vacation period. The probability that you will go to the beach is higher in the summer, as is the probability that you will swim and be attacked by a shark. And you will probably buy an ice cream when it’s hot. But no-one would argue that these factors (ice cream sales and shark attacks) are really connected. Yet this is what many people do all the time in less obvious cases.

Coming back to RCTs, there are several types of these trials; they may or may not be conducted “blind”, meaning that either the scientist or the patient, or sometimes a third party, does not know which intervention the subject has received. Trials may employ a number of different interventions, called “arms”, and may involve either individuals or groups of individuals. RCTs are difficult to conduct, expensive and sometimes very time-consuming. And even if we reach this highest level of proof and believe in the levels-of proof system, RCTs have their limitations, and their results are not always reproducible. Lastly, they are not always appropriate, and sometimes frankly impossible to carry out. Let us review briefly why one would not conduct an RCT. First, RCTs can be unethical. This is obvious, but not always clearly stated. For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, the Chinese ran studies on what is a vital organ and what is not. They therefore arranged randomised trials in which they removed a person’s heart, and oops! Fatal! And in another individual they left the heart. Obviously, random selection of people and extraction of their organs is contrary to our ethical code. RCTs can be inappropriate when it is not possible to isolate the intervention from the factor to which it is being compared, and I will speak of that in a moment. Third, in my personal opinion, when a trial will not provide additional proof, it should not be undertaken. Thus, if an RCT cannot be done or is inappropriate, there remains a whole series of other methods, from collecting the opinions of experts to the well-designed non-randomised trial. Each has its advantages and disadvantages, its pros and cons.

The aim is to secure the soundest possible proof given the constraints. We have spoken only in theoretical terms to this point, and now I will speak of the reality. First, reproducibility. Why is it important? Ideally, it should be possible for the studies to be reproduced by other, independent organisations and in different contexts. One study is not enough, and does not carry as much weight as several studies do. How are these studies reproduced? On the basis of studies published in peer-reviewed journals. The underlying theory of this type of publication is that the research submitted for publication is examined by experts in the field. In theory, peer review is impartial, which means it should be anonymous and independent. You submit an article to a journal, which sends it out for peer review. Now, imagine that I am a peer reviewer and the authors are anonymous. I do not know who did this work, and the author submitting the paper does not know that I am one of the peer reviewers. This also ensures a diversity of opinions. For if only one person at a journal made the decision concerning the article or the research, we would have a dictatorship deciding what was right and wrong Thus, the aim is to ensure that several people give their opinions of the quality or merits of the work. Why is it so important? With these peer reviews, journals become scientists’ debating forums. Publications are a form of emulation: people will reproduce the results and challenge them. Publications also serve to document what is happening, because science and scientific progress build on past knowledge. The mere fact of publishing research draws attention to a particular problem, and it is the common currency of our discussions – that is, the “scientific currency”, the way scientists assess things.

Now let’s speak about the reality: behind this nice theoretical picture, what is really going on and what are the implications for nutrition? At the top of the slide, you can see the scientific method that I showed you in the first slide. At the bottom, you can see what really happens in many cases, and it is very different. The first step in the scientific method consists in observing what happens, but in reality, what often happens is, “I will start up a study on what ‘they’ told me that ‘they’ would like to establish as true”. In the Epicentre-MSF context, this could mean that the Mali programme manager wants a study to demonstrate the success of the programme and that I am supposed to find a way of doing so. Instead of formulating an hypothesis, scientists and researchers then design the minimum number of experiments needed to show that the theory is true, instead of designing the best experiments. Sometimes, people change the theory to fit the data – or vice versa. Then they publish an article and claim they are using a scientific method. Next, of course, if someone dares to utter a criticism, they defend themselves vehemently. This happens often. I am joking here, but when you think about it, it is not really funny.

Why is it so complicated? Why is it so difficult? You see here a slide from a study on diarrhoea-induced mortality – one could just have well have written “nutrition-induced”. I tried to imagine a situation in which someone told me, “I would like you to conduct a study showing that the incidence of diarrhoea was reduced by half in 2009”. This cannot be done in an RCT, because thousands of things happen and it is very difficult to isolate one element among them. This is not impossible and I am not trying to say that you should not do it, I am simply pointing out the problem raised by such a situation.

I have isolated here a dozen problems out of those commonly encountered. The first and main problem is very often that the hypothesis or objective of the study is unclear or incredibly vague. There is also the difficulty connected with multiple interventions, as indicated in the previous slide.

Next, there is the question of individuals in the context of scientific research: if we are good doctors, we put the patient’s health first, whether the patient is participating in a study or not – that is, we should, but it doesn’t always work that way in the context of a research study. In addition, the context in which the study is conducted must stay the same, must remain comparable, which is a recurrent difficulty. Such studies are expensive. Their results are not immediately available. Sometimes scientific knowledge changes more quickly than the timing of the study itself. We may start on a study that is to last, let us say, two years, but during those two years other things can happen: other research projects are completed and other knowledge is accumulated. Scientists and readers also often make mistakes in interpreting statistics or the meaning of figures and findings. Rony Brauman can speak of this much better than I can. Just because something is quantified does not make it scientific or legitimate.

The same is true of publications. Rony Brauman mentioned this a few moments ago, but I will say it a bit more abruptly. Publications have many biases. The first is that if one is conducting a study and wants to do things right, it must be published in a journal so that it becomes part of the body of scientifically proven facts in order, ultimately, to serve in formulating a scientific or medical policy. The problem is that, if the result of a scientific study is nil, the study becomes uninteresting and has little chance of being published, which is a very important bias. Then there is the question of language: I am speaking here in English, and this is a good example. Research topics are biased in themselves: many more studies are published on Viagra than on malnutrition. There are even biases connected with the titles of scientific studies, since people like catchy, hard-hitting titles. There is also the “I owe you one” bias, which is very common: if I am reviewing a paper and, even though in theory I do not know the author, I might know who wrote it and I might say to myself: “the study is poor but I know the guy who wrote it, he’s helped me in the past, he’s a nice chap. I will not refuse the paper”. There is also the “well-known author” bias, which might be called the “Robert Black bias”:Professor and President, Bloomsberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University.scientists who have a big reputation can write what they like, and frankly, I don’t think their papers are at risk of being refused. There is also the “belligerent” bias: people reject papers simply because they have the power to do so. And the probability of being published is very low when one has never published before – the “unknown author” bias. This makes things very difficult. More experienced authors can add their name to the paper to help out a young author, because even if the study has been well conducted it is highly improbable that it will be published.

Why am I telling you all this? Why is it important? This raises the question of why we undertake scientific studies. There are three main reasons for doing so. First, we conduct scientific studies when we do not know something, and it is often basic research. Second, we conduct studies when there is not enough of a consensus on what should be done, on the appropriate treatment. The third reason – which is often Epicentre’s area of intervention – is when a consensus exists but is not acted on for one reason or another. For example, why are country protocols different for ACT malaria treatments or HIV treatment? When one knows what may be the right treatment for a given disease, and that treatment is not used, one needs proof to demonstrate it. The reasons why it is not used may have nothing to do with science: they may stem from ignorance, or from a decision not to follow a protocol that is too expensive, or from political or cultural motives. Whatever the case, one may want to demonstrate that a particular protocol can be applied even in contexts where such considerations may arise.

To answer Jean-Hervé’s question: can a treatment and a programme be evaluated in the same way? No. If you decide to conduct a scientific study, the plan of the study should depend on the question you are trying to answer, on the constraints encountered and, of course, on the level of proof desired. A quick assessment of a programme and a five-year RCT are very different undertakings: the goals are different, the target audiences are different, and they are conducted for different reasons. But above all, when we evaluate a programme, we are evaluating a whole set of things simultaneously – Michelo used the word “packages” this morning – and not one thing in particular.

Why is this difficult in the case of malnutrition? The decision to formulate a programme or policy can be based on something other than science. It may be based on arguments relating to equity, justice or other factors, which do not depend on a scientific study. Scientific language and the scientific process, though very important in themselves, are also tools available to people, who will decide when to use them and when not to use them, depending on whether there is any point in their doing so. This is true of humanitarian organisations like MSF. When we develop a policy stance, sometimes we will use scientific arguments, and sometimes not. I like to think that this is the primary reason why I do this work, and why CAME exists, and why CRASH exists. There are different ways and means of achieving our objectives, and science is only one of them.

DISCUSSION OF REBECCA GRAYS’ PRESENTATION

Jean-Hervé Bradol

– To get the discussion started: should milk be used in the food supplements given to children with moderate acute malnutrition? There is a good deal of scientific information in favour of using milk, but its price is an obstacle. Reading the report of one of the last meetings of the MSF International Working Group on Nutrition, we note that one of our teams, partnered with a Danish university, the WHO and the WFP, wants to study the composition of the therapeutic food to prescribe for moderate acute malnutrition. A three-arm study is proposed: one group will receive a mixture of cereal paps and milk, another group cereal paps only, and a third group no food supplements at all. Does this research proposal correspond to the state of scientific knowledge? Do we still need to verify that milk is useful in treating child malnutrition? Is it quite ethical to plan such a trial? In my opinion, such research is neither scientific nor ethical.

Jean Rigal, medical director, MSF, Paris

– There is no valid reason to question the role of milk in the diet of young children. The European experience on this point is instructive.

Susan Sheperd

– RCTs were developed in a special context, in response to the introduction of new drugs that had severe secondary effects, and whose effectiveness had not been scientifically established in comparison to the previous treatment, which was the standard. This methodology may not be applicable to other questions.

Rebecca Grays

– Must the scientific studies conducted in the areas where we operate meet the same standards as those which prevail in Paris? It is possible to carry out RCTs in very different environments. But is this a good idea? No, unless the aim is to isolate the effect of one intervention or treatment from the effects of others. More generally, the main question is not always scientific; there are other arguments that at times are more appropriate to the problem being studied.

Rony Brauman

– One remark: your description of the ideal scientific method is still much too idealised. The starting point is not an observation but a theory that governs the objects that you will observe; thus, we do not move from observation to theory, but from theory to theory, and this is also true of scientists. This is important because it lead us to question the presuppositions, which are “scientific” to varying degrees, that govern the measurement of such or such an object, comparison of such and such a group or parameter, etc. Can the impact of an acute malnutrition prevention programme be measured? Ultimately, if we want to sum up the main issue of this seminar, this is where it lies.

Rebecca Grays

– What do you mean by the impact of the programme?

Rony Brauman

– Can we say that distributing Plumpy’doz reduces the number of children who become subject to acute malnutrition?

Rebecca Grays

– Yes, but that is an evaluation of the impact of all the project components, not of Plumpy’doz alone. That would be different from an RCT comparing Plumpy’doz to other products.

Jean-Hervé Jézéquel

– Rebecca’s presentation shows the limitations of the scientific method. It also shows the mismatch or misalignment between the time constraints and rationales of humanitarian and scientific stakeholders. If they are to work together, humanitarian and scientific stakeholders must take this problem of alignment into consideration. I would like to know what our colleagues in Operations, concerned as they are with the need to provide scientific proof, thought of Rebecca’s presentation. In Niger in 2005, we did not do an RCT to prove what we were convinced of at the time, namely that mass treatment of children in the southern Maradi region was needed.

Susan Sheperd

– There was at least one RCT before that.

Vincent Brown, epidemiologist, MSF general management

– Plumpy’nut has been widely used by operational staff without scientific studies since the late 1990s. Since then, we have been asked to prove not that the children put on weight but that Plumpy’nut is a good product. This is absolutely absurd.

Marc Poncin, Niger desk, MSF, Geneva

– We cannot say today whether Plumpy’doz works. The study in Zinder province was interrupted owing to tensions with the government of Niger. The point of conducting these studies is to provide quasi-scientific evidence so that we can convince other players to use the same protocol. Once we are convinced that a protocol yields good results, we try to simplify it as much as possible so that it can be employed in less privileged environments than those of MSF projects. One of the perverse effects of using anthropometric norms in the project in Niger’s Zinder province was to make us forget that there is more to children’s health than nutrition. We missed the importance of malaria in child mortality, because we were too focused on nutrition.

Laurent Gadot, health economist , MSF Campaign on Access to Essential Drugs

– On the question raised by Rony Brauman: how many cases of severe acute malnutrition were avoided through the distribution of Plumpy’doz? This is the key to the World Bank’s approach to assess how much money is needed to fight malnutrition around the world. To estimate this, the Bank would like to have scientific studies as a basis. But the debate is not limited to its scientific aspect. It is obvious that feeding individuals prevents them from suffering from malnutrition.

Jean Rigal

– In the history of medicine, the classification of mental illnesses was greatly changed by the introduction of medication. Diagnosis and therapy were changed by the discovery that certain molecules act in certain ways. The introduction of ready-to-use therapeutic foods has changed not only the way we look at malnutrition but also our mode of operation. Geza Harczi and Isabelle Defourny’s 2006 paper on the treatment of moderate acute malnutrition with Plumpy’nut has had a considerable impact, though it was not a randomised trial. Scientific studies are necessary, but we must remember that the way they were conducted was long based on empiricism. We should also note that randomised trials have taken some of the steam out of drug research.

End of the second session

3RD SESSION: STAKEHOLDERS AND THEIR POLICIES

Is the fight against malnutrition a matter for political action, education, agricultural and economic development, or for medicine? Are all these spheres of action opposed to one another or complementary? Are the Millennium Development Goals on hunger, poverty and infant mortality realistic? Is the reluctance of some countries to treat acute malnutrition legitimate? Is the intention of providing care, here and now, reconcilable in practice with that of influencing public policies for a better future? Ultimately, what are MSF’s ambitions in the field of nutrition?

PRESENTATION BY STÉPHANE DOYON, CAME

My presentation will try to describe, in necessarily summary fashion, the recent changes and differences in the way the major international organisations view the problem of malnutrition and how to respond to it. I will conclude by giving my view of what ambitions MSF might have for the fight against malnutrition and what goals we might set in this respect.

There is a relative consensus today for the UNICEF multi-causal explanatory model (see diagram below), although this model still raises a number of questions. The model identifies all the factors that may influence the nutritional status of a population, that is, the structural and indirect determinants of malnutrition (the economy, education, level of development, etc.) as well as the more immediate factors (disease, diet, etc.). These are all factors that affect the living conditions of a given population, and hence its nutritional status.

Conflict situations generally destabilise these structural factors (through massive population displacement, destruction of the economic and social fabric, etc.) and frequently lead to situations of severe nutritional imbalance. I will not analyse nutritional interventions in this type of context, since to my mind there is a broad consensus on the subject, particularly within MSF.

Operations raise more questions when we are faced with situations where there is not a clear acute situation, a crisis or declared emergency with a well-identified trigger that explains a high level of malnutrition. Examples from the contexts where MSF operates would include the situations of Niger and Burkina Faso. People often ask what the point is of treating malnutrition in these contexts where malnutrition is classified as chronic. It is therefore worthwhile to consider the positioning of the various stakeholders, as well as the various obstacles they evoke to oppose treatment of malnutrition.

Diagram: the causes of malnutrition in children (source : unicef.org)