Michaël Neuman & Fabrice Weissman

Director of studies at Crash / Médecins sans Frontières, Michaël Neuman graduated in Contemporary History and International Relations (University Paris-I). He joined Médecins sans Frontières in 1999 and has worked both on the ground (Balkans, Sudan, Caucasus, West Africa) and in headquarters (New York, Paris as deputy director responsible for programmes). He has also carried out research on issues of immigration and geopolitics. He is co-editor of "Humanitarian negotiations Revealed, the MSF experience" (London: Hurst and Co, 2011). He is also the co-editor of "Saving lives and staying alive. Humanitarian Security in the Age of Risk Management" (London: Hurst and Co, 2016).

A political scientist by training, Fabrice Weissman joined Médecins sans Frontières in 1995. First as a logistician, then as project coordinator and head of mission, he has worked in many countries in conflict (Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kosovo, Sri Lanka, etc.) and more recently in Malawi in response to natural disasters. He is the author of several articles and collective works on humanitarian action, including "In the Shadow of Just Wars. Violence, Politics and Humanitarian Action" (ed., London, Hurst & Co., 2004), "Humanitarian Negotiations Revealed. The MSF Experience" (ed., Oxford University Press, 2011) and "Saving Lives and Staying Alive. Humanitarian Security in the Age of Risk Management" (ed., London, Hurst & Co, 2016). He is also one of the main hosts of the podcast La zone critique.

3. Practices

The Duty of a Head of Mission

Interview with Delphine Chedorge, MSF emergency coordinator in Central African Republic, by Michaël Neuman

This article is based on interviews conducted between May and July 2015. Translated from French by Karen Tucker.

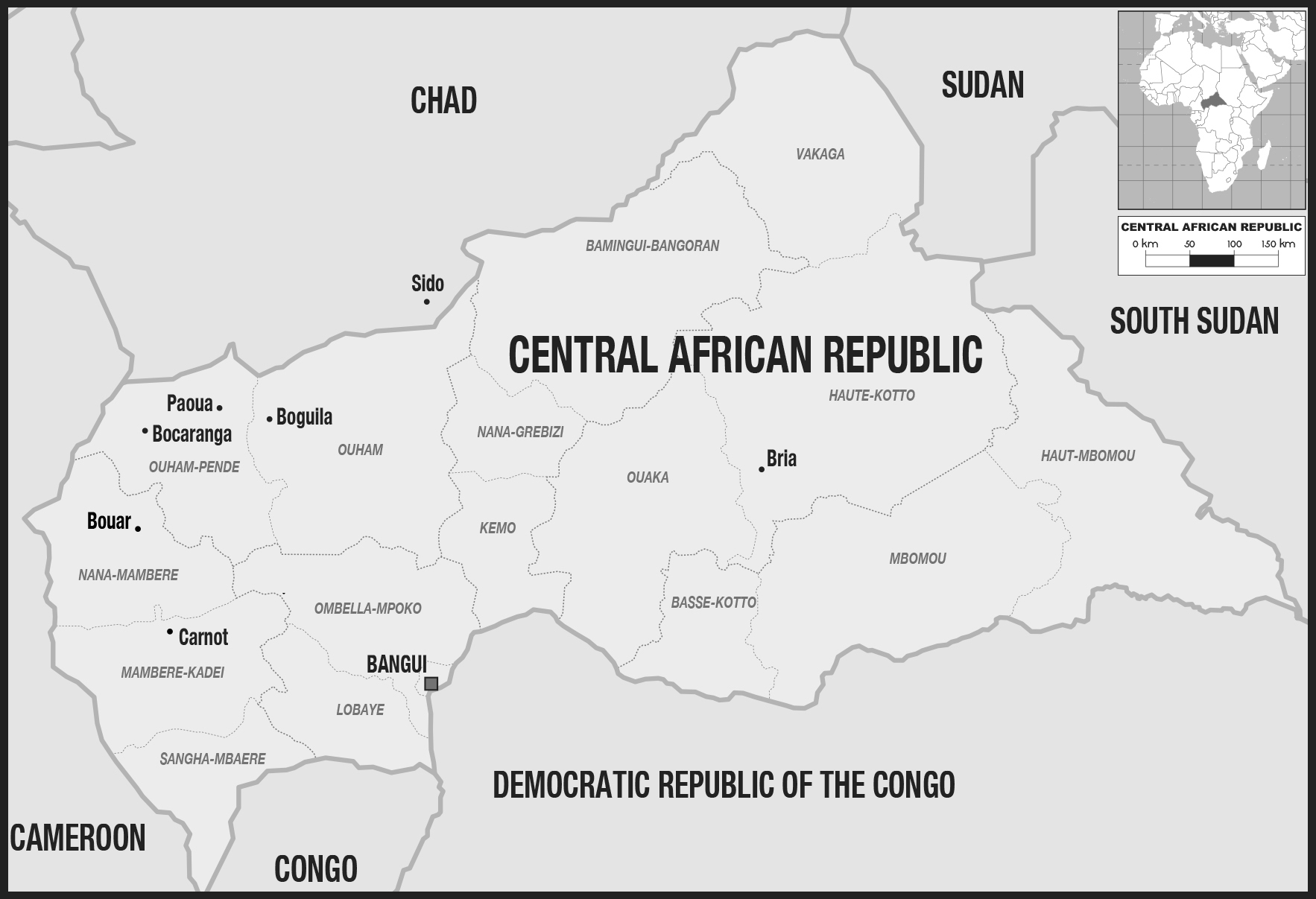

Landlocked Central African Republic (CAR) has a population of 4 million people and a wholly inadequate healthcare infrastructure. In terms of funding, the country ranks first for MSF-France and third for the MSF movement as a whole, after the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan.“International activity report 2014”, Paris: MSF.

Also one of the most dangerous countries, four MSF employees have been killed in its conflicts since 2007. In 2014, 300 international and over 2,500 Central African staff members worked on some twenty medical projects.

MSF emergency coordinator Delphine Chedorge headed the French section’s operations in CAR from January to December 2014. She spoke with Michael Neuman about the everyday life of a head of mission in charge of team security. The interview is preceded by a summary of the recent events leading up to the bloodshed in CAR.

The 2013-2014 Crisis in the CAR

The CAR has experienced a cycle of violence unprecedented in its postcolonial history. In March 2013, an alliance of armed opposition movements, the Seleka, seized power and installed Michel Djotodia as president. During the months that followed, the new regime’s violent attacks against the population and the previous government’s forces led to the formation of local militias. The result of an alliance between village self-defence militias and members of the former national army, these so-called “anti-Balaka” groups echoed the population’s mounting anger against a government increasingly perceived as “foreign” and “Muslim”.See, in particular, International Federation for Human Rights, “Central African Republic: They must all leave or die”, Press Release, June 2014.

Amid growing tensions and the fear of sectarian massacres, on 5 December 2013 the United Nations Security Council voted to dispatch an International Support Mission (known by the French acronym MISCA) to Central African Republic to re-establish state authority and protect civilians. MISCA was placed under the supervision of the African Union, with backing from French military operation “Sangaris”. The same day, a large-scale offensive by anti-Balaka militias against Bangui failed to bring down the regime and resulted in the flight of ex-SelekaWe will use the term “ex-Seleka” to describe the Seleka forces who are still active after they were disbanded by a decision of President Michel Djotodia in September 2013 following an increase in violent attacks and abuses.

rebels and the stepping-up of the international military deployment. After the anti-Balaka and some of the civilian population looted and committed massacres against Muslims living in Bangui, who had been left unprotected, the routed ex-Seleka launched an onslaught of unrestrained violence.See, in particular, Human Rights Watch report, “‘They came to kill us’: Escalating atrocities in the Central African Republic”, 19 December 2013.

With his back against the wall, President Djotodia gave into international pressure and resigned on 10 January 2014. However, the appointment of a transitional government did not restore the stability that had been hoped for. The ex-Seleka continued their bloody retreat toward the countries on CAR’s north, east and west borders with anti-Balaka groups in hot pursuit. Meanwhile, the anti-Balaka encouraged and led massacres against Muslims forced to flee to neighbouring countries or the few enclaves within CAR protected by international forces. A retrospective mortality survey conducted in April 2014 by MSF among CAR refugees in Sido in Chad revealed that 8 per cent of those who had fled died between November 2013 and April 2014, with 91 per cent of these deaths attributed to violent acts committed during the campaign of persecution against Muslim minorities.

At the time of the attempted coup d’etat of 5 December 2013, MSF’s French section was running three projects in the country—primary and secondary healthcare programmes in Paoua subprefecture in the north-west, where it had been working since 2006, and paediatric services in Carnot and Bria. In December, the section set up an emergency operation to care for the victims of the conflict, with particular focus on Bangui. The Spanish and Dutch sections were also working in CAR and were joined in early 2014 by the Swiss and Belgian sections.

Michael Neuman: What was the situation when you first arrived in CAR?

Delphine Chedorge: My first assignment in CAR dates back to the summer of 2007. I’ve been back several times since, for three months in 2012, then for one year in early 2014. I started off as emergency coordinator and in April I became head of mission. The current conflict began in December 2012 and intensified after the Seleka took power in March 2013, which led to the collapse of the country’s security forces. So in a sense, I “missed out” on just over a year of the conflict’s progress. During the first few weeks I had a hard time getting a handle on the security situation. What’s more, my knowledge of the country was very localised as it was centred on the north-west, where most of MSF-France’s programmes have traditionally been concentrated. I took some time to get to grips with what was going elsewhere in the country. And, personally, I wasn’t expecting such a violent sectarian conflict to break out.

What were the biggest security issues in Bangui when you arrived?

When I landed in Bangui in January 2014, there was lots of shooting in the city, including near the Hopital Communautaire, where we were treating the wounded, and our living quarters and offices. Everyone was in the same neighbourhood, right in the middle of an urban war.

It was also very difficult to get to the Muslim enclaves and neighbourhoods. In January and February we made several attempts to fetch casualties from so-called PK12 district where groups of Muslims wanting to flee had assembled and were under constant attack from particularly unpredictable militiamen. PK12 was also notable for its close proximity to an ex-Seleka camp. International forces were stationed there to protect civilians and the ex-Seleka, which created a really tense atmosphere. Sometimes we met with so much hostility we had to turn back.

National and international staff alike were highly exposed to danger. They often had to negotiate with armed, aggressive individuals entering the hospital to look for a particular patient or demanding to be treated ahead of the others. They witnessed first-hand the ferocity of the violence and its consequences in the numbers of casualties and types of wounds requiring treatment. Because of fighting nearby, the hospital team repeatedly had to seek shelter in the bulletproof operating theatre—which the in-patient tents weren’t. Staff members were experiencing high levels of physical and mental fatigue. Nobody was hurt, but the risk was high. No one asked to leave, which would’ve been perfectly understandable. We brought in psychiatrists and psychologists to debrief the teams.

What steps did you take to reduce the personnel’s exposure to danger?

When I first arrived, the head office security focal point was already there helping the teams to protect themselves, for example, from stray bullets entering houses, which had happened several times since December. He set up safe rooms that the staff used when the fighting was close-by. The hospital team were also afraid of staying at the hospital, especially overnight. So we decided that they would only work there from 8am to 4pm. We had to assume responsibility for patients having less access to medical treatment.

We sometimes designed our activities in a way we thought would increase our security while trying to establish more trust with armed groups and civilians (it was sometimes hard to distinguish between the two). For example, while treating victims of the violence that occurred in the Fatima neighbourhood in May and June and which caused fifteen to twenty casualties among the displaced population, we also ran mobile clinics in neighbouring Christian districts. Obviously, these clinics did serve a useful medical purpose—such as treating infantile malaria—but the primary motivation was to avoid being accused of working only with Muslims, even if our health centre in mainly Muslim PK5 district did, of course, provide care for Christians as well.

We also worked hard on getting information. The primary sources were the national staff, most of whom I had known for a long time. They described to me what was happening in the various districts, the groups, their weapons, what they were saying, the rumours and threats they were spreading. They also helped me identify which streets were dangerous. I wasn’t familiar with Bangui’s roads because MSF had no programmes there. We had to make a micro-political analysis of the dynamics in each of the city’s districts. We drove all over the city observing the situation. We used a driver who said he felt comfortable driving around certain neighbourhoods and he provided a running commentary on what was going on.

We worked quite well with the other MSF sections present in Bangui. One had established a working relationship with ex-Seleka while another had more recent ties with anti-Balaka groups due to their work in the M’Poko displaced persons camp.Following violent attacks in December 2013, tens of thousands of displaced persons originally from Bangui assembled at the city’s airport, Bangui-M’Poko.

During the early days of my assignment, we were fairly dependent on these contacts. We worked on the basis of trust—let’s say, not blind, but informed trust. It was hard for me, but it made sense. There were only so many contacts I could handle. Beginning in April, I regained control of contacts in cooperation with my colleagues from the other sections.

Could you also rely on outside information, from journalists and other NGOs working in the country?

Our information mainly came from three networks: missionaries, Ministry of Health medical staff and national Red Cross staff. All were very active in protecting civilians or providing relief when the fighting was at its most intense. We were also in regular contact with old acquaintances—all kinds of political officials, former rebels and district leaders. In addition, the person who had the job of head of mission when I arrived had developed her own network of officials working for some of the other NGOs operating in CAR and we were also in contact with several UN agencies and some of their staff.

At the beginning, there were few organisations delivering aid and travelling around the city and the rest of the country. The United Nations and the French army, followed by the European force EUFOR and later INSO (an NGO specifically responsible for security), gradually set up systems to provide information—usually incomplete and unreliable—to humanitarian organisations. The organisations responsible for keeping others from harm—which is more especially the military’s job—would say “avoid going here or there” or “take an armed escort”. There was some value in giving their advice serious consideration, but it was also important to maintain our decision-making autonomy. In the final analysis, and this was instructive, it was less the information itself (sometimes no more than rumours with no attempt at objectivity) than what it taught us about how much we could trust those providing the information and what they were willing or not willing to share.

Concerning the national staff, were there any specific security issues or requests?

Most of the Central African staff in Bangui lived in neighbourhoods severely affected by the conflict and they were very afraid of moving around the city. In December 2013, many of them stopped coming to the office. Coordination had set up a shuttle system to pick them up. This system closed down in early February 2014 as there was much less fighting in the city and taxis were running again. Despite this, employees regularly stayed overnight in our offices and houses because they couldn’t get home. As of September, being identified as an MSF employee no longer afforded protection and actually posed more of a risk, as employed people have money. Because of the gang culture invading Bangui, their security was jeopardised far more than ours. And, even more dramatically, all our Muslim employees had left the city, and most of them probably the country. We still don’t know what’s happened to many of them.

What were the main security problems outside Bangui?

Until October, we were occasionally able to travel by road in the interior of the country, despite a number of incidents. Of course, NGO and UN employees were sometimes targeted, but it was more for the equipment. In January 2014, a group of ex-Seleka stole a car from us. They stopped us, explained they needed a car for a day or two, took away our radio and MSF stickers and unloaded the car. We got it back after putting pressure on their commanders. The car had been used in combat. The same thing happened when an anti-Balaka group “confiscated” our truck and its crew before returning it a few days later. The truck was also used in combat. This type of “respect”, albeit relative, gradually disappeared over the course of the year. The risk was greatest on the roads, with anti-Balaka roadblocks manned by drunk, drugged-up fighters with no real chain of command. We had to limit travel by road and hire an extra plane to relieve staff and supply our programmes. This seemed to be the only option that would allow us to work in security conditions that we deemed acceptable. This decision was the subject of regular and exhausting discussions with head office who felt that the plane cost too much.

During this period, MSF-France was working in three locations, in Paoua in the north-west, Carnot in the west and Bria in the east. How did the security situation in these three areas evolve over time?

We were expecting Bria and Paoua to be the most vulnerable because they had been affected by the conflicts of the early 2000s. But Carnot ended up suffering the worst violence. There were numerous clashes between civilians, anti- Balaka, ex-Seleka and then Cameroonian MISCA forces, who were acting as a buffer between, on the one hand, the anti-Balaka militias and Carnot’s inhabitants, and on the other, Muslims trapped in the enclave who had barricaded themselves inside the church. The team witnessed massacres of Muslims on several occasions, especially in January, when we had to call on Cameroonian MISCA forces based a few hours away by road to the north to intervene to prevent Muslims being driven out of their homes and killed.

Displaced Muslims attempting to get medical treatment were at great risk and many refused to go to hospitals because of the extreme danger involved in getting to them. However, the team were able to negotiate with the anti-Balaka militias and some inhabitants a safe passage for the MSF ambulance transporting wounded Muslims and MISCA soldiers so they could be evacuated by plane to Bangui.

After clashes between international forces and anti-Balaka, in July 2014 a Fula patient was lynched inside Carnot hospital. This was one of the most serious incidents that had ever occurred in one of MSF-France’sprogrammes. You then began a “mobilisation campaign"—first local, then national—calling for the protection of healthcare facilities. What were you hoping to achieve with public statements about a security incident?

We probably should have done it sooner because we realised that some of the health workers were in fact not surprised that sectarian groups were settling accounts inside a health facility. Our message was: the hospital provides care for everyone and we cannot tolerate any violence; otherwise, we’ll have to leave. The team went to ask all the local health and political authorities, armed groups, local people and neighbourhood leaders to get all their contacts to spread the message that this was not normal. We succeeded in getting the message through.

Then, when we talked with the team and the other sections of MSF, we realised that what had happened in Carnot could happen anywhere. That’s why we decided on a national campaign, which included other MSF sites. We used posters and radio broadcasts to call for the protection of our medical activities.

Wasn’t it somewhat futile to call for the protection of health facilities on the basis of humanitarian principles?

It doesn’t hurt to use these magic words, so long as they’re followed up with a conversation and much more tangible negotiation. When an incident occurs, we try to determine the cause of the problem and our role in it. We also try to figure out how we can continue operating and providing relief in the particular environment. In the case of Carnot, it was in everyone’s interests that we stay. But our communications were not limited to the campaign. The local press in CAR published all public statements made in response to security incidents. Despite the lack of public reaction from politicians, some of our contacts did call us—even if only to see how we were coping. By speaking out, we could also counter government rhetoric about the supposed “normalisation” of the situation, which Central African and international officials (with France taking the lead) began claiming in late 2014. In view of the increasing number of robberies at homes and offices belonging to other MSF sections operating in the country, attacks on vehicles on roads, extortion and the seizure of our transporters’ trucks, it was important to make a point.

Central African Republic is where MSF-France’s last international volunteer was killed. It was in June 2007and the victim was Elsa Serfass, a logistician with the Paouaprogramme. You first worked in CAR in the days and weeks following this tragic event. Did this incident affect the way you managed security during your most recent assignment?

My greatest and most constant fear was losing a member of our team. I used to bring up Elsa’s death in my briefings with volunteers. Telling the story provided an opportunity to remind them about all the weapons that were circulating and the state of chaos in the country. This was important because, even in 2014 during a time of extreme violence, as soon as the situation calmed down for a few days, some team members could be quick to forget that we were working in a dangerous country. You also have to be honest with people coming to a programme and give them specific examples, such as murder, rape and lynching of patients.

I believe it is unacceptable to hide serious incidents from people arriving in the field. Even I found myself without information about a number of serious incidents—including sexual assaults—against colleagues in other sections. This led to some tense conversations. Managers sometimes tend to withhold information because they want to protect the dignity of the victims, but this information is vital to assessing the shifting nature of the risks teams are exposed to.

And, there’s a risk of the violence becoming trivialised. People immersed in a dangerous environment where incidents are commonplace can become inured to danger and no longer react to it because they end up seeing exposure to violence as the norm.

What were the circumstances that led you to suspend operations or evacuate staff during your assignment?

In 2014, when we thought there might be a significant deterioration in the situation, we carried out several preventive evacuations to reduce exposure to danger. For example, during the violence that took place in Bangui in October, we decided to evacuate twenty-four people by road and boat to three neighbouring countries over three days. And then there was the attack against Boguila hospital in April, which left nineteen people dead, including three of MSF-Holland’s national staff. We had lots of discussions with the heads of mission of the five sections working in CAR about how we should respond. There were two opposing opinions. The first advocated closing all projects in the country for a set period of time in the slim hope that such an extreme decision would provoke a reaction from the armed groups. The second, more moderate, opinion, mainly supported by MSF-Holland’s head of mission, called for evacuating just the international personnel and staff relocatedThis refers to Central African staff who are mainly hired in Bangui and then relocated by MSF to programmes in other parts of the country.

from Boguila. In the end, we chose the more minimal option of limiting care to emergency cases across all programmes for one week. An exception was made for Boguila, where international and relocated employees were withdrawn for a longer period and replaced with spasmodic visits. We found out who was responsible for the killings—a leader of an ex-Seleka group. But we didn’t speak out and release this information to the public. Instead, we complained to his superiors and waited to see what they would do. But to no avail as he’s still at large.

MSF’s operations in Paoua ended up being suspended for the longest period, even though the area had been the least affected by the war. How do you explain that?

In August, our Central African employees began making a series of demands, which they backed up with a strike. They wanted salary increases and transport allowances. We didn’t agree to these demands so they decided to call a day of strike, while maintaining minimum service. During the strike, which took place in September, picket lines were set up and some employees who wanted to continue working were seriously threatened. The local authorities who had agreed to act as mediators were accused of being traitors, which raised the question of whether we could continue to operate. The team was finally evacuated in December after international staff began receiving death threats. They made a gradual return, but only at the very end of the year.

MSF has been working in Paoua since 2006. How would you explain this deterioration?

The first factor has to do with a context specific to Central African Republic, the deteriorating labour relations resulting from the many years of violence in the region and the absence of State representatives and local government mediators—and all this against the backdrop of an economic crisis. Other organisations also had to deal with very difficult labour conflicts. The second factor is internal to MSF. During the year, five people had successively held the position of project coordinator in Paoua and this lack of continuity definitely impacted our ability to make a clear assessment of the worsening situation, particularly regarding labour issues. What’s more, we were taken up with the other programmes because we felt their teams were at much greater risk so, for sure, the coordination team didn’t monitor the situation closely enough.

In general, how much autonomy do project coordinators have to assess and handle security?

It depends on the person and how our relationship develops. Not everyone has the same amount of experience or the same ability to analyse the situation they find themselves in. For example, when I consider the explanations and precautions aren’t sufficiently convincing to justify a journey, I can refuse to give my authorisation. When you feel that your team leader has a handle on all this, you can give more autonomy.

We partially delegated the security of one team to another organisation: Catholic missionaries, as it happens. This is a very rare occurrence at MSF nowadays. For a few days in late January 2014, we left a small two-person team—an anaesthetist and a surgeon—in Bossemptele to the north-west of Bangui with no car or means of communication. This was at the time the ex-Seleka were taking flight and the anti-Balaka were carrying out violent reprisals against the town’s Muslims, causing many casualties. Wounds were becoming infected because the Central African doctor at the missionary hospital was out of the necessary supplies. So we decided to send two people to give them a hand.

This was a really specific situation. The Catholic mission was actively defending and helping Muslims in the area, the priest was accustomed to interacting with all of the armed groups, and there were missionary nuns there too. The mission compound was relatively well protected. I left the team there without a car. At the time, having a well-maintained MSF car would have attracted the militias’ attention, so not having one was actually safer. The team was almost invisible, but nevertheless, all the political and military groups were aware they were there; we didn’t act surreptitiously.

In Central African Republic as in other places, MSF has in recent years decided to ban some volunteers from working in certain programmes on the basis of their nationality and the colour of their skin. How did we get to this?

We decided to do this in two cases. In April 2014, a logistician was attacked in Bria for being white and French. French Sangaris forces present in the area were seen as taking sides against the Muslims and we were at risk of being associated with them. The first step we took was to pull out the volunteer. Then we decided to stop assigning white people there at all, since they might have been thought to be French. We soon realised that this was an isolated incident; the perpetrator had been upset and angry because his son has been killed in the fighting. And, in fact, lots of people had jumped in and defended the logistician.

Nevertheless, there could have been more cases like that, so, after talking with the team, for several months we kept to our decision. Considering our overall operational volume and the number of international staff in the country, we were simply making our jobs easier. But we didn’t prevent visits by the coordination team working out of Bangui. These increased, to such an extent that the restriction lost its meaning. We definitely could have brought white Western staff back in faster.

Then came the issue of staff with Muslim backgrounds. To avoid any problems, we adopted a super-pragmatic position because we thought that North Africans would be seen as white by the anti-Balaka. As for the Africans, some of them changed their first names to less Muslim-sounding ones. This was left up to each individual. On the other hand, I myself refused to appoint a Malian Tuareg as deputy head of mission because the nature of his job would have meant showing his face as he moved around Bangui, which would have posed too much of a risk.

Among the issues relating to security in Central Africa, the extent of MSF’s exposure was a major concern. Many people felt there were too many staff on the ground: 300 international employees, eighty of them in the French section alone, and 2,500 national employees in all MSF sections. What was your position on this issue?

You have to remember that Bangui is the most dangerous city in CAR and it’s where the coordination team is located. It’s also the city with the largest team. If you add the employees working at the hospital and our health centre in PK5 to the coordination team, there can sometimes be over forty-five international employees.

What’s more, head office’s decision to reduce operations in order to limit our exposure to danger contradicted their policy of deploying “first assignments” [or “first missions”, to use NGO-speak] to the field. In an environment that was unstable at best, and frankly dangerous most of the time, jobs were created to meet the need to train new volunteers rather than immediate operational requirements. It was completely contradictory and done without my agreement. In Paoua, for example, this was the case of two volunteers out of a total of eight and, after the violence that occurred in Bangui in October, I had to get them out via Chad in dangerous conditions.

At the beginning of our interview, you mentioned the role of the security focal point—an innovation for the French section instituted in 2013. The focal point’s appointment coincided with the operation department’s introduction of systematised “security management tools“, such as the risk assessment matrix and the system used to record and file information on security incidents known as “SINDY”. What do you think of these measures?

The logbook for recording incidents occurring in the areas where we operate, the guides, briefings and emergency public statements issued after incidents— all these were nothing new. The security focal point helped us make the team aware of the security environment and contributed to briefings, particularly with the logisticians tasked with setting up security measures (communications, safe rooms and tracking travel). This aspect was useful. Then, when he returned to head office in Paris, he insisted that we keep the SINDY database up-to-date. SINDY is a centralised system for filing reports on security incidents affecting only MSF.See Chapter 4, box: “Security Incident Narratives Buried in Numbers: The MSF Example”, p. 67.

This we disagreed about because I didn’t feel it was of direct benefit to the field. We already had logbooks and incident registers for recording important events to be taken into account in analysing the security environment. I’m sure it’s useful for MSF as an institution to keep a database of reports of the most serious incidents but, given that we were already very busy, I didn’t think it was necessary to do head office’s secretarial work. What is important is working with the team on managing incidents and sharing the information with the other sections. And the other danger with using SINDY in the field is that people will only see the problem from the MSF perspective and overlook incidents affecting other agencies.

To get back to the risk assessment, isn’t there something scary about making an exhaustive list of the threats you might be facing?

Yes, I ask myself that question. But in my experience, when I use the risk assessment during briefings I’ve noticed that the people I’m talking with become calmer and more focused as the conversation goes on. Their eyes are opened and they become more aware of their environment. In the end, after these conversations, people feel prepared and confident because they know the situation has been well thought out.

The idea is for people to be on their guard. There needs to be a balance between trivialising and exaggerating the risk.

At MSF and other organisations, there’s a certain amount of protest against the growing number of security rules in the field. One of your head of mission colleagues who spent a few weeks in Bangui said that “the curfew rules treat volunteers like children and encourage them to flout the rules’’.

Of course this happens; it’s a natural consequence of rules. But the volunteers didn’t seem particularly reluctant to comply with them. When they did flout them, it was in a way that didn’t put them at too much risk. That’s what we ask of people: when you break a rule, make sure you know why and how. If we need to, we’ll talk it through again and, if necessary, we’ll change it.

For example, when you ban your teams from going to the flea market in Bangui, is it because you worry there might be be serious problems or is it because you might have to deal with the theft of a careless volunteer’s bag?

What actually happened was that ordinary petty thieves got themselves grenades and were more and more violent. Also, you don’t manage forty international staff the same way you manage ten; you can’t talk to each one, look into every issue, etc. We definitely wouldn’t have had the same rules if there’d been five or ten of us in Bangui, but we were forty to fifty. It also explains something that was occasionally contested. When the security situation in town settled down enough to allow volunteers to go out, different curfew hours for weekdays (9pm) and weekends (10pm) were introduced. I never thought the city was less dangerous at the weekend. On the other hand, from a personal point of view, a simple question of fatigue, I couldn’t allow myself to be on call every evening of the week to deal with a car stopped at a police checkpoint on the way back from a restaurant. I was okay with being available an hour later at the weekend in case of problems so they could have more freedom. It’s a shame the teams couldn’t manage small incidents like these without outside help but it wasn’t always the case. I was making life easier with these rules. They were geared more toward management of human resources than security management.

***

BOX: The Case of "Dangerous Patients" in Yemen's Governorate of Amran

“I would not want to be a doctor here.”

Interview with the Amran project coordinator.

Already in 2010, well before Yemen became engulfed in all-out war between Houthi rebels and factions supported by Saudi Arabia in 2015, national and international staff working in MSF projects in Amran GovernorateLocated in the north of the country, the governorate has a population of around 1 million inhabitants. viewed the situation as highly dangerous.

Khamer, where MSF has been in charge since 2011 of all the hospital’s departments with the exception of the Ministry of Health-run outpatient Department (OPD), had been a peaceful town where international personnel were free to walk around—except at night, because of stray dogs. However, during the period from 17 April 2010 to 15 June 2013, MSF project coordinators in Khamer and in the nearby town of Huth, recorded twenty-three security incidents, none of which involved the death or kidnapping of any MSF employees. Verbal threats were a daily occurrence and being threatened at gunpoint was commonplace, as were shootings in the hospital compound and car-jackings. International employees were not usually affected, while Yemeni medical personnel working in the emergency room (ER) were more exposed than staff in the inpatient department (IPD). The most serious incident had been a revenge killing in 2011 that resulted in a patient’s death at the hospital.

Such incidents led several Yemeni doctors to leave the projects. In 2012 alone, one surgeon left after being verbally threatened by the relative of a patient he had operated on, a doctor after being forced at gunpoint to treat a patient, and a third after he was slapped. A local doctor interviewed in 2013 commented: “There is a 20 per cent chance I get killed in the hospital, 80 per cent chance I stay safe.”

This situation prompted the programme manager for Yemen to request an investigation into the logics of violence and the reactions to this violence of MSF and Ministry of Health staff. Conducted in July 2013, the investigation was based on interviews with patients, personnel and local authorities, mission archives and a review of pertinent social science literature on Yemen. Its main findings are presented below.

“Some Patients are Dangerous, We Know It”Interview with a member of hospital management, Khamer.Referring Patients for Security Reasons

In interviews, most Yemeni and international doctors tended to blame the insecurity on the lack of education of patients and their families and an “archaic tribal system living off the lack of strict regulation of government allowing any member of a tribe to do whatever he wants.”Interview with a hospital director, Sanaa.

People from villages outside Khamer—the primary target population of the project—were perceived to be the main troublemakers. The doctors recognised that this perception influenced their medical practices, as one of them explained:

"When patients come from communities with whom we’ve had problems, it bloats, and then, the therapeutic decision has no longer any medical and scientific rationality. It is quite common to hear comments such as: ‘this one is from this family’, ‘he is the son of that one’, ‘he comes from this region’, etc. It has a significant impact."Interview with an international doctor, Khamer.

In fact, it was common for patients with alleged “dangerous profiles” to be referred to other medical facilities in Amran or Sanaa, even if their medical conditions did not warrant it. There was very little disagreement among Yemeni and international staff that, “if there is a security risk, it is better to refer.”Interview with a Yemeni doctor, MSF, Khamer.

In some cases, the decision was at the discretion of the night supervisor, a non-medical staff member who “knows everything and everybody.”Interview with a Yemeni doctor, MSF, Khamer.

“Promises Are Not Followed by Acts”17. Interview with a Yemeni doctor, former MSF employee, Sanaa.Dealing With the Sheikhs

When a serious incident occurred, MSF frequently reacted by seeking the mediation of local tribal authoritiesThe concepts of “tribe”, “subtribe” and “family” in the context of Yemen are the subject of academic debate. As Paul Dresch puts it in “Tribalisme et démocratie au Yémen” (Arabian Humanities, no. 2, 1994), tribes are “evidently, not [...] very solid group[s]”. Although central to the understanding of social and political dynamics, the tribe is a malleable concept: “a very important flexibility in term of conflicts and alliances potentially exists.” and sometimes suspended its activities to put pressure on them and their tribes. In most cases, after a period of suspension varying from one day to six months, mediation was successfully concluded, compensation paid—money, cows, or guns—and victims apologised to by culprits in a gathering of local leaders. This reactive approach to insecurity was criticised by some staff members for its ineffectiveness. Given that doctors could expect little protection from the various local institutions, staff demanded that MSF play a more assertive role in ensuring safety. A Yemeni doctor formerly employed by MSF commented:

"The only thing we’ve been doing lately is incident, apology ceremony, incident, apology ceremony, incident, etc. We have to think about it in a different way."

The international team seemed to believe that the sheikhs were all powerful, if only the right one could be identified. As a member of the international team said, “He can do whatever he wants with his people”. However, some academics question this assertion, echoing the view of many Yemeni staff. As political scientist Laurent Bonnefoy explains, it is unreasonable to expect the sheikhs to prevent violence from occurring. Controlling violence in North Yemen is based first and foremost on “mitigation” and “regulation”, rather than on “prevention”, in an effort to ensure that conflicts do not get blown out of proportion and stay contained within acceptable limits.Interview, June 2013. See also Nadwa Al Dawsari, “Tribal governance and Stability in Yemen”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2012.

“Doctors are Parasites which Live on Human Blood.”“Yemeni doctors cause more harm than good”, National Yemen, 18 July 2012.

MSF’s reaction to the violence appeared to overlook as a source of tension the poor relationship between doctors and patients. Generally speaking, Yemeni doctors appeared to suffer from a very poor image, as illustrated by an article published in National Yemen in July 2012 entitled “Yemeni doctors cause more harm than good”:

"Thousands of Yemenis fall victim to medical errors at the hands of doctors, whose unearned and undeserved titles and certificates are the only things which connect them with the practice of medicine. (...) Many Yemenis have expressed their dissatisfaction with Yemeni doctors, who they say are not good at their jobs and have transformed their sacred profession into a way to earn money. Many have gone so far as to liken doctors to “parasites” which live on human blood."Ibid.

Some aspects of the operational set-up appear to have further exacerbated the general distrust. Lack of clarity in ER admission criteria was often mentioned as a factor of tension by both medical staffand patients. The ER saw around half of the total number of patients who arrived in triage, between 1,500 and 2,500 a month, while the other half were referred to the Ministry of Health’s OPD, run by three doctors from the former Soviet Union, where services were not provided free of charge.

Many patients refused to be referred to the OPD and exerted pressure on medical staff to be treated by MSF. As one interviewee explained, “the more vocal the patients are, the better chances they get to be seen by the MSF doctor.” Many people viewed this medically unjustified discrimination as the source of most of the problems encountered by the hospital’s employees, and this was without taking into account, as a Yemeni MSF doctor explained, “our watchmen, our staff, nurses, nurses’ assistants, they are taking their friends, their relatives to treat them. Sometimes we, the doctors, refuse, and sometimes, we don’t.”

Some patients did not understand why MSF delivered mostly emergency services and not, for example, care for chronic diseases and non-urgent surgery,The maternity, paediatric and adult medical departments admit non-emergency patients; patients with leishmaniosis and rickets are also provided with non-emergency treatment.

nor why they would be or needed to be referred to other facilities where they would have to pay. Routine profiling of patients by doctors according to where they came from and their family and tribal affiliations added to the tension. What’s the point of having a hospital if it cannot be accessed?

The layout of the hospital also contributed to tension in and around the maternity ward.

"Part of the problem is that there is no waiting room in the maternity—the building is too small. So the families generally wait outside while the women are in labour. Sometimes it can last for hours, during which the family are left in the dark, uninformed about how things are going if the midwife in charge does not take the time to come out and talk to the families."Interview with an international midwife, Amran.

Brief analysis of the incidents MSF staff encountered revealed their extreme diversity, as much in origin as in manifestation. Ultimately, the issues confronted by MSF in Amran were framed, for the most part, within a demand wholly comparable to that experienced by MSF and health professionals in hospitals all over the world: a quality relationship between patients and health personnel. At the hospital in Khamer, MSF operated in a setting where this expectation may have conflicted with the reality on the ground, given that the high level of violence in the region appeared to be generally socially accepted and that intimidation is integral to social regulation there. The investigation revealed that, while humanitarian organisations do not have to see themselves as passive victims, neither do they have to view Yemeni patients as inherently dangerous.

***

Security Issues and Practices in an MSF Mission in the Land of Jihad

Judith Soussan

Translated from French by Philippa Bowe Smith.

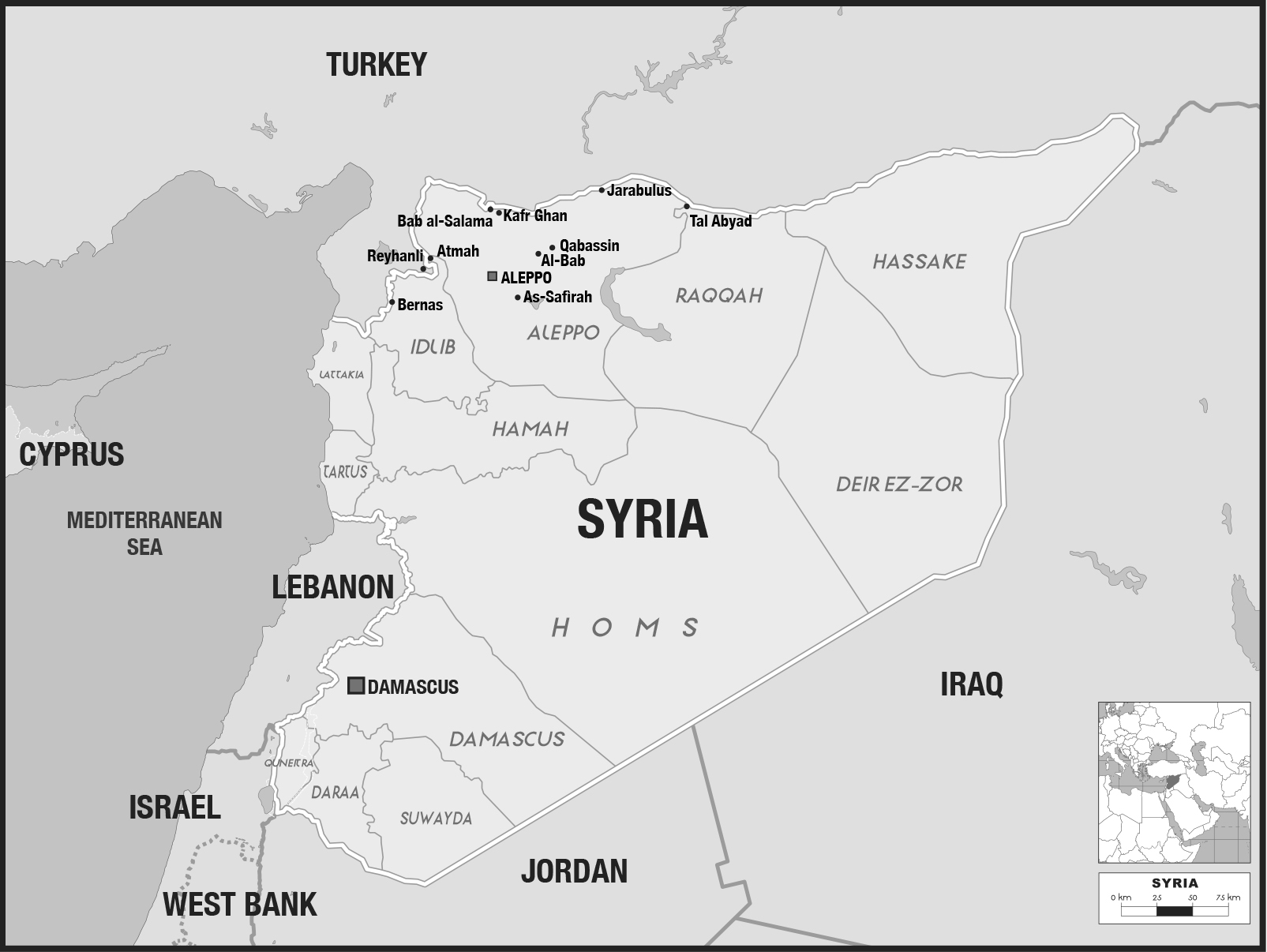

On 11 May 2013, the coordinator of the Qabassin project sent an email to the coordination team in Turkey announcing the opening of the MSF hospital that very morning. He summed up with a downbeat “so far so good.” He was certainly being modest, for there was much to be proud of. This was the first hospital set up by an NGO and with international staff to be located deep inside Syrian opposition-held territory rather than along the Turkish border like MSF’s other projects: the hospitals in Atmah (MSF-France), a few kilometres as the crow flies from the coordination team’s base in Reyhanli in Turkey, Bab al-Salama (MSF-Spain), Bernas (MSF-Belgium) and Tal Abyad (MSF-Holland). It had taken six weeks of extensive refurbishment to turn an empty building into a clean and well-equipped facility with surgery and maternity units, an emergency room and a twenty-five-bed inpatient department.

However, the opening of the Qabassin hospital, a small but significant event, did not get the attention it deserved. A bomb exploded the same day in Reyhanli, killing fifty-one people and injuring over 150, while the previous day armed men in Atmah verbally attacked and threatened to kill a Swedish MSF staff member they accused of spying. He then had to appear before a local Islamic court. In comparison, Qabassin seemed almost a haven of peace and the members of the team, all newly arrived and enjoying a quiet life during their time off, walking around the town, visiting the market and receiving invitations to take tea, had trouble taking the coordination team’s calls for vigilance seriously. “They were too relaxed, they’d forgotten where they were,” recalls the head of mission at the time.

This chapter tells the story of the Qabassin mission from the security perspective. It examines the perceptions and practices of the team in the field (starting with the field coordinators, who came and went at a rapid pace) and the coordination team in Turkey, with whom they were in permanent contact.To avoid any confusion arising from successive changes in staff, we will indicate in pp. [111-116] the footnotes the period during which a particular project coordinator or head of mission was present.

How did these people analyse their situation, the prevailing risks and events as they unfolded? What behaviours did they adopt in the face of danger—from the rules and procedures (introduced, modified or forgotten) to the various strategies designed to “reduce exposure” and “improve acceptance” (to use current parlance)? This chapter will pay particular attention to moments when disagreements arose, during which people’s often complex definitions of the word “security” were revealed and came into conflict.To explore these questions, we consulted all the literature produced by the Qabassin mission: field reports (“sitreps”), security documents (“security guidelines”) and, especially, daily emails exchanged with the coordination team. Interviews with over twenty people involved on the ground, in the coordination team and at the head office in Paris were also conducted between January and June 2015. We thank them for their time and their help. This study does not include any views from the team’s Syrian personnel, fascinating as it would have been to have heard their opinions on the situations they faced, the decisions taken and various people’s attitudes. For reasons of feasibility, this was always going to be the case.

Finding the Right Role in the War (Mid-2011 to Early 2013)

Exploration (How to Find Protection from Bombs?)

With the organisation’s first attempts to take action in Syria in mid-2011, MSF-France’s approach toward its operational positioning took the form of a common dilemma—how to operate within the context of the Syrian civil war and reach out as much as possible to its victims, without exposing teams to excessive risks or compromising quality of care.

It took the emergency desk team a lot of patience, several false starts, exploratory missions that failed to lead anywhere because the risks were considered too high, and finally a few pivotal encounters for MSF-France to open its first project in Atmah in June 2012. MSF was, as it’s now called, “embedded”, as the hospital and house where the international staff were accommodated and their security were all provided by a highly influential Atmah public figure, who was also a doctor and a member of one of the local Free Syrian Army (FSA) brigades. The many months of patient strategising and exploration in an environment where foreigners were strongly suspected of spying resulted in the watchwords: keep a low profile.

The Atmah project now open, MSF started to look for ways to reach out to areas more directly impacted by the conflict. Those behind the Syria programme had their eyes firmly fixed on Aleppo, a city split into a government zone and a constantly bombed FSA zone. But after an exploratory mission in August 2012, operations managers in Paris deemed it too dangerous and rejected the idea of sending in international staff, especially in light of the loyalist force’s targeting of field hospitals.In the end, MSF-Spain opened a project in the “industrial district” on the outskirts ofAleppo in mid-2013.

Two further attempts to deploy operations failed. In October 2012, a hospital project set up in partnership with some Syrian doctors in Kafr Ghan near the Turkish border had to close three weeks after opening due to fundamental differences between MSF and the Syrians on how to run the hospital. Then MSF turned to Al-Bab, a city with 130,000 inhabitants situated some thirty kilometres from Aleppo along the route used to evacuate casualties. The project was well advanced when, in January 2013, the town was repeatedly bombed and the coordination team evacuated the project team to Turkey. In the words of the head of mission: “I told them, ‘we’re in the same situation as the Syrians, we’re not protected. So we need to find a safer place.’”Interview with the head of mission (January-June 2013), 17 June 2015.

The database he had compiled showed that, out of all the places in a ten-kilometre radius around Al-Bab, the town of Qabassin had never been shelled. The team had also heard that its population of 20,000 Arabs and Kurds included a not insignificant proportion of people who backed the regime. And, unlike Atmah, where black-clad foreign Islamists paraded in their pickups, there was no visible armed presence. This was why, so it was said, Qabassin was untouched by the turmoil among opposition groups and bombing by pro-regime forces. On 27 January, the day after they were evacuated, two members of the small team decided to go to the town.

Opening the Project (How to Gain Acceptance ?)

They carried on the work of identifying and meeting with key contacts initiated during the two months spent in Al-Bab. In addition to members of prominent families, they had met with representatives of nascent revolutionary institutions—the civilian-run local council, whose responsibilities included health, and the Islamic court, which handled justice and policing. The project coordinator had also established contact with representatives from local politico-military groups, including brigades affiliated with the FSA and Islamist groups such as Al-Qaeda affiliates Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra. While maintaining these contacts in Al-Bab, they became acquainted with the small world of Qabassin. They met with influential local leaders, some of them also members of the local town council (there was no Islamic court as yet), as well as representatives of the Kurdish party affiliated to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).Bravo [Qabassin] sitrep, week 7-8, 15 to 28 February 2013. “Tea. I drank a lot of tea during this period,” recalls the project coordinator with a smile.

The team driving the Qabassin project wanted to do things differently to Atmah (not to rely on a protector) and to the failed Kafr Ghan project (to avoid co-management). The hospital was to be “100 per cent MSF.” In terms of activities, however, the project was similar to the others, with surgery the focus to provide treatment to casualties evacuated from Aleppo via Al-Bab. The decision was also taken to offer general medical treatment and surgery to local people, a decision that, according to documents written at the time, met two essentially tactical objectives. First, to avoid appearing as a hospital for fighters, thus minimising the risk of being targeted for bombardment by the regime. Second, to gain better “acceptance by the community”Bravo sitrep, week 3-4, January 2013.

by allaying any possible concerns about the risks stemming from setting up a hospital in the town and offering services that people would probably need. The other major feature of the project would be to identify small medical facilities closer to the combat zone (including in Aleppo, which the organisation was not giving up on) that MSF could support as the situation evolved on the ground. These outreach activities would also enable MSF to channel sick and wounded to the hospital in Qabassin while monitoring needs engendered by local politico-military developments.

As preparations were underway, the team wrote an in-depth analysis of the risks and detailed the security rules. According to the Security Guidelines approved in March 2013, the main risks in Qabassin related to road traffic and the “psychological impact”, i.e. stress.Security Guidelines—annex 3—Bravo risk analysis, 26 March 2013.

In addition to these “high” probability dangers, bombing and crossfire were classified as “medium”, and chemical weapons as “low to medium”. The risk of kidnap—despite the abduction in Atmah on 13 March of two members of NGO ACTED—was described as low, “as we are well-known and well-accepted within the community.”Security Guidelines—annex 2—Bravo rules, 26 March 2013.

The security rules included standard procedures, for example relating to travel: in a car, wearing a seatbelt, carrying identity documents, leaving the Syrian driver to handle interactions with people manning checkpoints, and on foot, writing down destinations on the board used to keep track of where staff are going, and not walking alone or at night. But, a number of very strict and detailed rules governing personal behaviour were also laid down:

"1. Behaving appropriately towards staff/local people is the very first security rule. Do not shout or address people aggressively (...) No flirting/sexual relations between international/national [staff]. 2. Laughing out loud can give the impression of being drunk. (...) 4. NO PHYSICAL CONTACT WHATSOEVER between men and women (no hand-shaking, etc.). (...) Do not take ANY photos as people may think we are spies/journalists.Bravo Security Memo, summary of the rules accompanying the Security Guidelines, 25 March 2013.

Women must not smoke in public (...) Alcohol, illicit drugs and marijuana must not be taken or even discussed with Syrians. Do not discuss politics or religion. Dress appropriately outside the hospital at all times (men: no shorts, women: cover the head, arms, and legs no tight-fitting clothes)."Security Guidelines, annex 2.

In short, these rules formalised the need to keep a low profile, something everybody agreed on, which would lead to “acceptance”, as indicated in the words concluding the rules: “Better acceptance by the community = improved security”. It is worth noting that this notion of acceptance, introduced to MSF via security manuals,See Chapter 5, p. 71.

was used extensively by members of the mission to describe a very wide range of practices and behaviours: no smoking in public, providing maternity care and meeting with local authorities.

In early March, just as work on refurbishing the hospital was about to begin, an incident occurred that made it seem that a project would have to be abandoned yet again. A delegation of Qabassin residents informed the project coordinator that they opposed the opening of a hospital because they feared that the town, so far unscathed, would become a target of bombardment by the regime. Remembering the failure of the prematurely opened Kafr Ghan project, the project coordinator took the time to understand and make sure of the project’s backers and, during the period 9 to 16 March, he held numerous meetings. It transpired that the complaints were motivated as much by genuine fear as by frustrations stemming from the unequal distribution of the benefits prominent families stood to gain from MSF’s project. So, after reassuring them, the refurbishment began and the recruitment process was initiated. The incident made the team more determined than ever to be as objective and transparent as possible, and they interviewed 300 candidates, from surgeons to cleaners. At the same time, the team took care to achieve a balance between Arabs and Kurds and between the various families for all posts not requiring any specific skills.

A Peaceful Little Town?

Networking I. (Establishing a Network of Contacts—How and Why)

After the hospital opened on 11 May 2013, the medical team concentrated on setting up activities. Although Qabassin remained calm, bombing and TNT barrel-bombs dropped from regime helicopters were daily occurrences across the Aleppo Governorate and there were sporadic rumours about the use of chemical weapons elsewhere in the country. It was this specific threat that led MSF’s newly appointed (and very first) security focal point to make a visit to Syria in May 2013.

This was the background to the increasingly troubled relationship between the head of mission in Turkey and the new project coordinator, who had arrived in mid-April. The head of mission complained of “poor visibility” about the situation, which he blamed on inadequate communication on the part of the project coordinator.Interviews with the head of mission (January-June 2013), 17 June 2015, and deputy head of mission (June 2013), 6 February 2015.

He therefore asked him, starting with the tools and procedures, to show that he was paying sufficient attention to security matters. A morning and evening “security contact” was set up between the coordination team in Turkey and the project coordinator and initial hiccups further exacerbated tensions.Email exchanges between the logistics coordinator and the project coordinator on 4 June, 6 June, 9 June 2013, etc. This security contact had not been put in place beforehand: “What for? We talked to each other all the time anyway,” said the project coordinator who set up the project (December 2012-April 2013).

The head of mission accused the project coordinator of failing to use monitoring tools (the incidents database he had created and the board used to keep track of each team member’s movements). Above all, he asked him to provide more detail about the context and to improve his network building. This included getting to know the people controlling checkpoints and obtaining their phone numbers, maintaining links with various groups and meeting newcomers, for, as well as Jabhat al-Nusra (the Al-Qaeda affiliate already present on the outskirts of Qabassin), other Salafist groups started setting up offices in June 2013. “You must communicate, build your network,” the head of mission told him. In the Syrian context, where spy-fever was rife, and in the absence of anything specific to discuss, the project coordinator was firmly of the view that it was best to steer well clear:

“I felt it was necessary to stop asking people too many questions. (...) I’m convinced it was the right thing to do. Sometimes I feel it’s inappropriate, the way we turn up and start questioning people (...).

And then there are the things that I know [being Muslim] about people who are a bit conservative, with radical tendencies. You’re a guest; the fewer questions you ask, the greater your chances of being accepted.”Interview with the project coordinator (April-July 2013), 17 June 2015.

The same goes for the checkpoints: “Our laissez-passers worked everywhere; if they were letting us through, why ask questions?” He felt it more appropriate to observe and to “secure the relationship with our close entourage” of three or four regular contacts who had reassured him that “if the team toed the line, no one would harm us.” Far from being settled by the change of head of mission in late June, the disagreement merely intensified, as his replacement was particularly focused on documenting the political and military context.

Disquiet (How to Interpret Information?)

While rumours of a major “battle for Aleppo” had been circulating since late May, June and July were in fact characterised by tensions and incidents within the opposition forces. These included clashes between PKK-affiliated Kurdish forces from Qabassin and police units acting under the authority of the Al-Bab Islamic court, the town falling under the provisional control of these Kurdish forces, and a bomb explosion at the Jabhat al-Nusra base just outside Qabassin. There were also confrontations at checkpoints between FSA brigades and fighters from a group newly arrived on the scene, known to be an offshoot of Al-Qaeda in Iraq and not on good terms with Jabhat al-Nusra: ISIS/ISIL or the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham/the Levant.We will use the more common acronym: ISIS (the group took its present name, Islamic State (IS), in June 2014).

At the end ofJuly, the project coordinator reported back on these troubles, noting that, although Qabassin was currently “really quiet”, Islamist groups (which included ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra) further north in Jarabulus had announced their intention “of establishing an Islamic State” and had “declared that foreign NGOs are infidels and so not welcome in Syria.” He added: “We’ve got all these groups in Qabassin.”Bravo sitrep week 26-27, 25 July 2013.

His mission ended on 30 July and, one week later, his replacement arrived (the project’s third, including the set-up stage). From the start, he was alarmed by the situation he discovered, which contrasted strongly with the impression he had been given during his briefing back in Paris. As well as the heightened tensions between the various opposition groups, there had been two major incidents. The car bringing the project administrator back from the Turkish border to Qabassin after his leave had been held up by a group of armed men on the outskirts of the town. After apparently hesitating to kidnap the administrator, they had eventually left, taking with them the end-of-month wages he had been transporting. And, in Aleppo, an MSF-Spain car had been stopped by an armed group, and its occupants (a Syrian MSF logistician and two non-MSF passengers, said to be a Turkish contractor and his American girlfriend) were still being held prisoner.

By mid-August, the now very detailed emails the field team sent to the coordination team reported one concern after another. These included the team’s lack of preparedness for a possible chemical attack, renewed ISIS statements attacking foreign NGOs in Jarabulus and rumours of a group targeting British citizens for kidnap, etc.Email from the head of mission to the project coordinator, 13 August 2013.

The project coordinator informed the coordination team that he wished to cut back the international staff immediately. The head of mission acquiesced, but not with the same urgency. 15 and 16 August saw clashes between Kurdish forces and the FSA/Islamist groups at various points across northern Syria. On 17 August, fighting broke out in Qabassin and that evening the project coordinator wrote to the head of mission: “everybody is safe at the house (...) ISIS now controls the town.”Email from the project coordinator to the head of mission, 17 August 2013.

An MSF Mission in “The Clutches of Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham”

The first contact with ISIS took place at the MSF hospital when several combatants showed up after the fighting on 17 August. Two were injured and a third came complaining of stomach pains: “When we asked him to remove his coat, he said it was explosive and he couldn’t take it off.”End of mission report, project coordinator (August-September 2013).

The fighting had lasted just a day and calm was restored on 18 August. At the MSF house, the project coordinator and medical advisor interviewed each international staff member in turn. Were they willing to stay in an environment where “Al-Qaeda, in this case one of its affiliates, ISIS, is now fully in control of Qabassin?”Ibid.

Nine of the fourteen team members chose to leave the mission and, by 19 August, they were all in Turkey.Late that night, having interviewed all the team members, they applied the same process to themselves and interviewed each other in order to avoid prejudging their respective decisions (discussions with the project coordinator, March 2015).

The arrival of ISIS had enabled the project coordinator to get what he wanted and cut back the team in quite drastic fashion.

The five international staff who remained in Qabassin did not rule out following the others to Turkey. “What are we waiting for? For them to start executing our patients against the wall behind the hospital?” asked the nurse.Reported by the project coordinator, interview, 23 June 2015.

Predictions went back and forth between the coordination team and the team in the field. The project coordinator reported that a Syrian staff member said: “They want to establish an Islamic State [in Qabassin].” “That doesn’t necessarily mean there’s no place for MSF,” replied the head of mission, “it depends on the degree of tolerance of the group as a whole as well as on their commander here.” To which the project coordinator replied: “Can you give me one example of a place where they have sole power, where they have proclaimed the State, and where people like us are tolerated for very long?”Exchange ofemails between the project coordinator and head ofmission, 19 August 2013. Based on his twenty-five years’ experience with MSF (including eight years as president), the project coordinator was not optimistic. His research backed up his instinct: “I went online to look into their behaviour in recent years. In terms of civilian casualties, they’re quite simply the most murderous of Al-Qaeda’s branches,” he wrote a few days later.Email from the project coordinator to the head of mission, 25 August 2013. As well as using the Internet, the project coordinator asked the medical adviser to show him how to use Twitter so that he could track statements and rumours circulating on that platform.

Yet, on 19 August, the new ISIS representative in Qabassin paid the project coordinator a visit, assuring him that MSF could stay and work in safety. He agreed to put this commitment in writing:

"In the name of Allah, the beneficent, the merciful,

Thanks be to Allah, peace and blessings be upon his prophet Mohammad.

From now on, the MSF hospital can continue treating all cases without bias to any party. MSF will consult the Islamic State in Qabassin if any problems arise at the hospital. And the Islamic State takes responsibility for protecting the hospital in the event of any danger. All doctors, men and women, can carry on working at the hospital."ISIS letter, cited in email from the project coordinator to the head of mission, 20 August 2013.

Networking II. (What Does “To Drink Tea” Signify?)

MSF also received unsolicited written support from important local contacts such as the local council and the Al-Bab Islamic court, whose various members were wary of ISIS’s takeover of Qabassin. Right from the beginning of his mission, the project coordinator had met with as many people as he could and had even established cordial relations with some of them, such as a military judge at the Al-Bab court with links to the Ahrar al-Sham Islamist group, and a prominent citizen of Qabassin and member of the Free Syrian Army. Several would occasionally turn up unannounced at the house to talk. “I didn’t really make any new contacts, but maybe I treated them differently,” said the project coordinator. So when, for example, the local council or the Islamic court approached him to provide material assistance to displaced people, “I said ‘ok, let’s go and see what we can do’, and that’s how we came to spend a fair amount of time together.” The project coordinator saw this as more about running the project than managing security. But time spent with local contacts did help to get a better grasp of the situation—the needs and the political currents—which he viewed as “the first stage in security.” He and other members of the team would spend evenings and Friday afternoons in the company of these contacts and, in these more informal settings, “we didn’t pretend to be neutral.” They would chat and listen to the Syrians’ accounts of “the early days of the revolution.”

"According to Syrian social norms, when you pay somebody a visit you score a point. (...) If you answer an invitation you are honouring your host. It establishes a connection, a situation where it’s ok for you to ask for something, or to be asked; it’s a two-way thing—are you prepared to trade? If the answer’s yes, then you need to establish relationships, while being aware of the social norms. (...) Sure, people ask you for favours, but then you ask for lots too! It worked both ways, and it’s absolutely vital that it does."Interview, 23 June 2015.

This is in very stark contrast to his predecessor:

“I don’t go to eat in people’s homes. You need to be careful about accepting an invitation. Sometimes it’s a two-way thing, and that’s not a trap I want to fall into. So, I thank them for the invitation, no more than that, and we respect each other.

You need to keep your distance; I can drink tea with them in the office, chat at the hospital or in the street without having to visit their homes. And as we didn’t know how the situation would play out. There’s a saying in Arabic: “remember that we have shared salt at my home.” (...) It related to my role as project coordinator. I wanted to maintain that distance that would allow me, if one day the need arose, to say: “I owe you nothing, and you owe me nothing.”Interview with the project coordinator (April-June 2013), 17 June 2015.

So, behind the consensual phrase “to drink tea” were two diametrically opposed practices.

Disagreements about the Situation Analysis

Despite reassurances obtained from local contacts and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, the project coordinator was still uneasy about the project’s future. He felt that the fact that the coordination team and head office seemed fairly reassured simply meant they were failing to comprehend the extent of the danger. This was the case regarding the management of several human resource issues. Replacing the administrator was the subject of heated debate. As the only Muslim and Arab-speaker among the international staff, he was known in the small world of Qabassin and thus had a vital role in maintaining and gathering information. The coordination team wanted him to end his mission at the end of August as planned, to which the project coordinator answered that he was willing to stay on for longer and that his departure would seriously endanger the mission. Questions about the number and profiles of international staff led to yet more disagreement. While numbers had been increased to nine in order to resume surgical activities, Paris wanted to send in more international staff as well as visitors from head office. And lastly, an American doctor who arrived at the end of August let it slip that he was Jewish. He was asked to maintain absolute discretion about his origins; already in early August, even before ISIS arrived, the project coordinator had been forced to replace a Sri Lankan doctor who had created upset among staff and patients in the emergency room when he revealed that he was a Buddhist.“For some groups in the area, being a Buddhist is really as bad as being a Yezidi (...) it can turn nasty.” Interview with the project coordinator, 23 June 2015.

Amid these preoccupations, on 21 August came the news that the regime had used chemical weapons in Damascus suburb Ghouta, a devastating manifestation of the threat that had been on people’s minds for months. The team on the ground asked the coordination team to send in drugs to treat a possible flood of contaminated patients as well as to respond to requests made by very worried local council health officials. There was outrage when they were told that the drugs they already had—enough to treat a few dozen patients— would suffice for now. They also wanted to prepare for the admittedly quite unlikely possibility of chemical attack against Qabassin or Al-Bab. The protective gear (suit, mask, gloves, boots) was a real organisational headache as it was hard to use, bulky and expensive. So the organisation had made its choice: the team in Qabassin had a little more protective equipment than there were international members of staff. Several team members found this unspoken hierarchy in terms of protecting lives hard to swallow; what were they supposed to do about the national staff, their families and the patients?“I worried about loads of dying people pounding on our door,” remembers the physiotherapist based in Atmah, where a similar situation arose (interview, 11 February 2015).

Adjustments (How to Justify MSF’s Presence in Light of the Risks ?)

“ISIS have asked us to continue to work with an international team in Qabassin. This is both dangerous and of little use,”Document attached to an email from the project coordinator to the head of mission, 23 August 2013.

was the project coordinator’s assessment in relation to what the project was delivering. He felt that the number of births was low (averaging ten per week) and that the hospital saw very few casualties, as most were treated at field hospitals set up by the various military groups (ISIS also had its own facility at a location unknown to MSF). The majority of procedures in the surgical unit were for burns (averaging twenty-four new cases per week), some very serious and which the project coordinator felt would be better treated in Turkey than in the MSF hospital. He therefore suggested “pulling out the international team from ISIS’s clutches before things go really wrong”, relocating the project to Al-Bab (where the opposition forces were more balanced, as reflected in the make-up of the Islamic court) and transferring responsibility for Qabassin to national staff.Email from the project coordinator to the head of mission, 25 August 2013. Two weeks later, heavy fighting broke out in Al-Bab between several political groups including ISIS (which was in the process of establishing a major presence), upsetting the balance of power and thus undermining the appeal of this option. “I didn’t agree!” recalls MSF’s president. As head of the emergency desk team when the Syria mission was being set up, he was still in contact with military commanders he had encountered in Atmah, one a Chechen jihadist who was a member of the Muhajireen (or ‘exiles’), which went on to become a key element of ISIS. The jihadist reiterated that MSF was not in danger in Qabassin.Interview with the president (formerly head of the emergency desk), 20 May 2015.

As for the head of mission, he argued that what had been achieved in Qabassin was not so bad, but authorised the project coordinator to further explore suggestions for adapting activities.

In the meantime, the team set out to redress the balance between the activities and the risks, by further developing activities. The doctor in charge of outreach, who had arrived at the beginning of August, was encouraged by the project coordinator to assess areas where displaced people had settled—they had already been visited by his predecessor but no action had been taken— such as As-Safirah to the south of Qabassin. In this constantly bombed area receiving no assistance whatsoever, small operations were set up to distribute medical supplies, tents and basic items, giving the team the sense of being “where we’re needed.”Interview with the outreach doctor, 28 January 2015; informal discussion with the project coordinator, March 2015.

Procedures for travelling to As-Safirah consisted of making contact with Syrian contacts on site (a doctor and displaced persons manager) the day before, then getting an update on the actual day, notably via Twitter. If the decision was taken to travel, the MSF doctor met up with the two Syrians just outside the bombarded zone. “Stay close to the guy with the walkie-talkie. He gets real-time military information,” the project coordinator instructed him.Informal discussion, 20 January 2015. “I’ve never thought of security as a geographical concept,” he says. “It’s all about finding the right network.”The MSF doctor exposed himself to risks that he says he was “ultimately” not ready to take. He confided: “I set aside time every Friday to ask myself whether it was worth being there” and every week he answered in the affirmative. Paradoxically, by increasing the volume of activities and running operations that were riskier—but that the team felt to be more relevant—identified dangers became more acceptable.