In a disaster situation: get your bearings, triage and act

Jean-Hervé Bradol

Article initially published in the book La médecine du tri. Histoire, éthique, anthropologie under the direction of Céline Lefève, Guillaume Lachenal and Vinh-Kim Nguyen.

On 12 January 2010, a high-magnitude earthquake caused numerous buildings in the city of Port au Prince in Haiti to collapse. Tens of thousands of people were killed or injured by falling blocks of concrete. The aftershocks from the earthquake, the predictions made by some seismologists and public rumours prompted fears of a repeat of the disaster. Houses, schools, churches, hospitals and business premises – all the places that had housed the capital’s residents and their main activities – had become lethal traps and a permanent threat.

For the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) team working in La Trinité clinic, their most urgent priority was to get themselves out of the buildings before they were buried and help the patients in the hospital to do the same. The top two floors of the clinic had collapsed to the ground. The number of people buried under the rubble was estimated at around ten. An anaesthetist, a cleaner and a surgeon were among the dead. Some were trapped in the rubble for several hours before they were released. It was sometimes possible to communicate with them and pipes were slid into the gaps to keep them supplied with water. Others, who were still alive after a few hours, were dying beneath the rubble. Whilst all this was happening, the team produced an initial review of the situation and asked for additional support from the organisation’s head office. Throughout the city, tens of thousands of injured people were trying to get out of the ruins with the help of their friends and family and get to a hospital that was still functioning.

As a result, for the first 13 days, the team from La Trinité treated several hundreds of injured people just lying on the ground1Observations gathered by the author, as a member of the back-up team for the mission.in the street or in the garden of a house that had previously served as a pharmacy, administrative offices and warehouse. Surgical operations were carried out in a metal container that had been hastily adapted for the purpose. In exceptional circumstances of this kind, where the demand for care explodes and supply collapses, how do you decide who to start with? The response recommended by learned societies and health authorities is to use a procedure borrowed from military medicine, known as triage. In the spirit of this procedure, a surgeon and an anaesthetist triaged injured patients from La Trinité under the supervision of the clinic’s medical director. Rather than using one of the standard protocols, they followed the spirit of the triage procedure as formulated by the World Health Organization2Emergency Situations Working Group – Transmissible diseases: surveillance and action, WHO Americas Regional Office, WHO office in Haiti, Évaluation des risques pour la santé publique et interventions. Séisme : Haïti, January 2010, p. 14

Pan American Health Organization. Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the World Health Organization, Establishing a mass casualty management system, Washington, D.C., 2001 : “Patients must be split into groups based on the seriousness of their injuries and decisions must be made about the treatments they can be given according to the resources available and their chances of survival. The principle on which these decisions are based is one of allocating resources to benefit the health of as many people as possible.” According to the WHO recommendation, the medical team responsible for triage determined the seriousness of each patient’s condition and therefore the order in which they were sent to the operating theatre based on the usual criteria (lesions observed, respiration rate, time for normal skin colour to return, heart rate, blood pressure, colour of conjunctiva, state of consciousness and temperature). A sheet was filled in and given to the patient or the person with them. The injured person was recorded and hospitalised under one of the makeshift shelters made from plastic sheeting. A team of technicians made sure that there was a generator to provide electricity and a tanker to bring in water supplies. Food was brought in by a caterer. The number of surgical operations increased day by day. In addition to the new cases who continued to arrive, there were injured people who had already had one operation and needed to go back to the operating theatre, if only to redress their wound in clean surroundings and with sufficient analgesic treatment. The operating theatre had to improve its performance continually to meet the multiple demands. The order in which people would be operated on was decided each morning and reviewed as the day went on, based on the new cases arriving. In the first 13 days, 1,275 injured people3Florian Cabanes, Pratique de l’anesthésie réanimation en situation précaire: Analyse d’une mission humanitaire avec MSF à Haïti lors du séisme du 12 Janvier 2010, medical thesis / speciaist subject anaesthesia and resuscitation, University of Paris VI, 15 October 2010.were brought in, triaged and cared for. Around 400 surgical operations were carried out. Across the country4MSF, Haiti earthquake response / Inter-sectional review / Executive report / Synthesis of six specific reviews from 12th January to 12th April 2010, 2010, Geneva.from 12 January to 30 April 2010, MSF teams – a total of 3,400 people at 26 sites – carried out 165,543 outpatient consultations and 5,707 surgical operations.

The example above shows that triage is necessary where there is exceptional demand, leading to the use of a specific procedure to establish priorities. Widespread use of the term triage and the clarification of its objectives date back to the First World War5Kenneth V. Iserson and John C. Moskop, Triage in Medicine, Part I: Concept, History, and Types, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Volume 49, no. 3: March 2007.: sorting out the injured to send those whose state of health allowed it back to their regiment as quickly as possible and organising care effectively in the hope of avoiding as many deaths and severe functional deficits as possible6The rest of this article will focus on the response to inhabitual deaths for the purpose of simplification. The same arguments would apply to functional deficits that are not life-threatening, for example the loss of the use of an eye, hand or speech, a persistent disabling pain, etc.among those who remained in the care of the medical services. Since the First World War, the uses of triage have diversified and become more extensive. Today, triage is most frequently used outside of its original context: so-called wars of position such as the First World War. It has found a place in the response to natural disasters, epidemics and famines and in managing more day-to-day situations associated with a scarcity of resources, as well as for determining the order in which patients in the waiting area of an accident and emergency department are seen or patients are selected for admission to intensive care.

What the Haitian example described above does not say is that before they triage individuals, emergency aid managers select which places and situations – and therefore populations – will be prioritised over others when it comes to providing assistance. In these circumstances, the different ways in which the misfortunes of various groups are presented in the public arena have as much of an influence as medical and health criteria on which populations will be dealt with first and which will have to wait or resign themselves to not receiving the help they anticipated. Every disaster takes place in a specific and changing social, cultural, economic and political context.

This emphasises the importance, for those responsible for organising emergency assistance, of a precise classification of the places, situations and populations seen as a priority. Wrongly triggering emergency procedures, including triaging individuals, would result in a futile disorganisation of care, with negative medical and health consequences. Conversely, not triggering an emergency procedure in time would expose treatment centres to paralysing bottlenecks at a time when the exceptional number of sick or injured patients requires rigorous administration of care.

This article looks first at the questions raised by selecting specific situations and then those posed by triage procedures as applied to individuals.

Get your bearings

The challenge is to trigger an emergency procedure at the right time, neither too early nor too late. Health monitoring is designed for this purpose and seeks to identify significant, more or less sudden variations that may suggest a catastrophic event, as soon as possible. Such an event can be described from three different angles. The first is demographic: a population, a number of cases and an inhabitual number of deaths in a given area at a given time. The second is social and political: the existence, or not, of tensions in society in relation to the prevention of the event and reactions to it. The third is institutional: the degree of emergency response by the public authorities.

Seen from these three points of view, there is a wide variety of disasters. Sometimes, events that cause few deaths lead to a significant level of social and political mobilisation, which prompts a disproportionate emergency response at an institutional level. In France in 2009 and 2010, for example, a significant amount of money (around 600 million euros) was spent in response to the H1N1 flu epidemic7Cour des comptes, La politique vaccinale de la France, communication à la commission des affaires sociales du Sénat, Paris, October 2012.,although epidemiological data did not show levels of incidence, lethality or mortality that were any higher than in previous years. Very often, the cause of the disaster is the subject of passionate debate. Was the flooding in New Orleans (USA) and its 1,8008 Richard D. Knabb, Jamie R. Rhome, and Daniel P. Brown, Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Katrina 23-30 August 2005, National Hurricane Center, 20 December 2005.victims the result of divine will, Hurricane Katrina or badly designed and poorly maintained dykes?

The duration of some disasters can also be disconcerting. Whilst the term ‘disaster’ is reserved for events that only last a short time, some situations – marked by high chronic mortality – are not seen as requiring a swift and massive response. In the Zinder region of Niger in the early 2000s, for example, food shortages and a high frequency of infections meant that mortality amongst children under the age of five was double9Institut National de la Statistique Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances, Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples, Niamey, Niger, 2006.that in the capital, Niamey. Was this not a sign of a long-term disaster in this region of the country?

Analysing disasters from the point of view of the scale of harm – deaths, injuries or illnesses and the destruction of property – is a good place to start in order to avoid falling into the main traps inherent in the initial evaluation of a given situation10The destruction of property is not analysed in this article.. This implies understanding what normal mortality is.

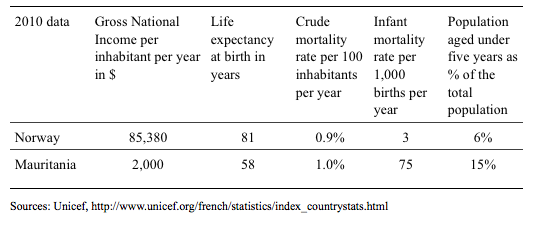

Epidemiology classifies habitual mortality as normal. In 2011, gross annual mortality rates varied11http://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicateur/SP.DYN.CDRT.INby country between 0.5 (Bahamas) and 1.6% (Afghanistan). In terms of ease of remembering, retaining the figure of 1% [0.5 – 1.6] of deaths per year as an estimate of what is normal regardless of the society concerned is useful in terms of quickly assessing the situation concerned. Is it not true that more people die in low-income countries? No, the number of deaths is not necessarily higher but life expectancy is much lower, mainly because of a large number of deaths in early childhood. In high-income countries, life expectancy is much longer, child mortality is low and most deaths are accounted for by older people.

For the event to be significant from a quantitative point of view, there must be a significant variation (multiplication by 2 or even more) in mortality compared with normal. A daily indicator is used for detailed monitoring of mortality in order to correct it as quickly as possible, namely the number of deaths for a population of 10,000 people per day (1% per year = 10 per 1,000 per year = 0.27 per 10,000 people per day). A doubling of the gross daily mortality rate, for example over the course of a week, should at least trigger an investigation. According to the Centers for Disease Control12 Interpreting and using mortality data in humanitarian emergencies. A primer for non-epidemiologists, Francesco Checchi and Les Roberts, Overseas Development Institute / Humanitarian Practice Network, network paper number 52, September 2005, London, p. 7.(CDC, USA), in normal times it should not exceed 0.5 per 10,000 per day (1.8% per year) and when it reaches 1 per 10,000 people per day (3.6% per year) it is imperative to trigger an exceptional procedure (an emergency) to reduce the number of deaths as quickly as possible. Having one’s eyes riveted on the figures, however, does not guarantee a sufficiently fast reaction. Health monitoring must also look at qualitative aspects and trigger an alert as soon as the first case of a highly lethal condition caused by a mechanism likely to produce a very high number of cases is reported: for example, the arrival of the first injured person from a neighbourhood that has been bombed or the diagnosis of a first case of cholera.

Understanding the context before deciding to act means not only knowing the level of mortality at a given moment but being able to grasp the trend over time. Providing emergency assistance in a disaster situation is a race against time, usually one that begins too late. At what point in the story does an emergency intervention come into its own? At the beginning, when there is everything still to play for? Or conversely, when the peak in the number of deaths has already been reached? Low mortality can indicate that it is already too late to hope that an emergency intervention will save large numbers of lives. The number of deaths may be normalised in this case, simply because of the recent deaths of a majority of the most vulnerable individuals.

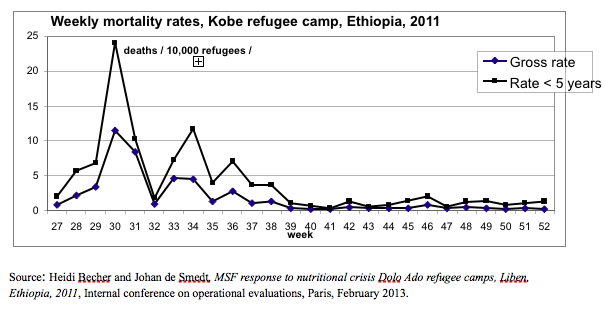

The change in mortality13Mzia Turashvili and David Crémoux, Review of the OCA Emergency Intervention in Liben, Ethiopia. Evaluation report, September 19th to November 15th, Vienna evaluation unit, MSF internal report, 2012.amongst Somali refugees in Kobe camp, Liben, Ethiopia in 2011 is an example of this type of situation, where normalisation occurs largely because of a demographic haemorrhage rather than because of the impact of emergency aid. The population had been weakened by a lack of food and by infections. A measles epidemic proved deadly amongst young, undernourished children. Emergency assistance was limited for months by the Ethiopian administration. When, in November 2011, international aid organisations including MSF14http://www.msf.org/article/ethiopia-surge-number-somali-refugees-demands-increased-capacitydecided to protest publicly, over 1,200 people out of a population of 25,000 refugees (4.8% in three months: June, July and September) had already died. Following the lobbying efforts, aid organisations were given access to new facilities by the Ethiopian administration but mortality had returned to normal since the beginning of October.

Mortality data are obtained from visiting cemeteries and consulting undertaker’s, registry office and healthcare facilities’ records or by carrying out a survey with a representative sample of the population. Constructing a representative sample means first knowing the size of the population and its distribution within a given territory at the time of the survey. Disasters are often accompanied by sudden demographic changes due to both population movements and high levels of mortality. The significance of an increase in the number of cases and deaths is not always obvious. It is important to draw a distinction between, on the one hand, a simple increase in the size of the population accompanied by a proportionate increase in cases and deaths, for example following an influx of people, and on the other, a worsening of the disaster, which explains the increases in cases and deaths whilst the population remains stable. The estimate of the size of the benchmark population, which is the denominator for any calculation based on proportions, is the most decisive information when it comes to interpreting all the other data and also the most difficult to obtain and monitor accurately.

Deciding on pertinent responses in the face of a disaster certainly requires an understanding of changes in mortality but other elements are also decisive and need to be accurately defined, for example, the event concerned, the choice of a benchmark population, the region and the period of time taken into account. During the 2003 heatwave in France, deaths related to high outdoor temperatures were not initially viewed by the authorities as a category of events that required specific gathering of information. Accordingly, no large-scale response was triggered during the event. The social and political crisis that followed reflected the media coverage of the massive influx of people into emergency departments and the 18,000 excess deaths15Denis Hémon and Eric Jougla, Impact sanitaire de la vague de chaleur d’août 2003 en France. Bilan et perspectives - Octobre 2003. Rapport remis au Ministre de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale. INSERM and Institut National de Veille Sanitaire, Paris, 26 October 2004. during the period of the heatwave compared with the same period in previous years.

The choice of the target population is decisive. A measles epidemic in a population of children with no particular health problems is not likely to cause many deaths. Conversely, a measles epidemic amongst children who have been hospitalised for severe malnutrition can lead to a very high level of mortality. In this case, because the excess mortality is related not to the general population but to a sub-population of hospitalised children, the impact is major but on a scale limited to the nutritional rehabilitation centre in question. The same number of deaths in relation to the total population of children of the same age living in the territory covered by the intensive nutritional rehabilitation centre could indicate a limited variation in the mortality rate.

Choosing which period of time to study is also important. Some phenomena are acute and sometimes seasonal. If the analysis dilutes the mortality they cause over much longer periods of time, the situation can appear normal. Conversely, in other examples, permanently high mortality can mean people forget that it is indeed a disaster. In Botswana between 2001 and 2006, because of the impact of the HIV epidemic, mortality16http://www.indexmundi.com/g/g.aspx?v=26&c=bc&l=fr varied between 2.4 and 3.2% per year. In 2009, it returned to around 1%. The improvement was due in part to mass distribution of HIV treatments.

It is also important to bear in mind that healthcare services do not simply confine themselves to responding to disasters but that sometimes they cause them. If medical and healthcare activities deteriorate too far, the poor operation of the healthcare system itself becomes a risk factor for a sudden increase in mortality. In some cases, the impact of the problems is not simply poor treatment for patients: the healthcare centre itself can become a highly iatrogenic place. A classic example of this type of phenomenon is the use of the same syringe and the same needle to inject a treatment into a large number of patients.

Triage

Triage does not apply only to the influx of patients resulting from the disaster. It also applies to routine activities, so as only to maintain those that have a direct impact on mortality due to common causes, outside of a disaster situation. Other activities should be suspended so that human and material resources can be assigned to completing priority tasks that support the survival of the largest number of people. It is important, for example, to retain the possibility of carrying out a Caesarian section even after 50 or so injured people have come in. Conversely, surgery to treat cancer can be deferred. In general terms, the aim is to concentrate resources in order to prevent an increase in the number of cases (for example, evacuating a population exposed to bombing or vaccinating against an epidemic threat) and avoid the deaths of people already affected (operating on people who are wounded or administering antibiotic treatments during an epidemic).

The effectiveness of triage relies on three useful but fragile assumptions17Dr Michel Nahon, Les principes généraux de la Médecine de Catastrophe, SAMU de Paris, lecture on emergency medical assistance, Université Paris V, January 2011.

http://www.urgences-serveur.fr/IMG/pdf/princip_cata_s.pdffairness in treating individuals, the fact of there being a single cause of harm and the adoption of standardised behaviours by carers. In theory, triage offers a mathematical demonstration of its superiority over the usual form of organisation by securing a better quantitative match between supply and demand for care, which in turn translates into a lower number of deaths.

Triage is supposed to be applied to everyone based on the same medical and health criteria, with the aim of being effective at a collective level and treating all individuals fairly. An idealised presentation of this procedure emphasises, in particular, that someone’s place within the social hierarchy will not be a determining factor in their access to care. Baron Dominique Jean Larrey’s name is associated with the invention of triage insofar as he wrote18Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, Mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagnes, Tome IV, J. Smith, Paris, 1817, p. 487.: “Men’s wounds must be dressed regardless of their rank, based on the seriousness of their injuries and the degree of intervention they require.” This promise not to take account of the place occupied by the patient in society, however, is not always easy to keep.

An example: in August 2012,19Author’s observations during a field mission in August 2012.the medical services in the part of Aleppo in Syria that was controlled by the opposition, were treating several hundred injured civilians and military personnel every day. Hospitals and their staff were targeted by enemy bombardments. This is a typical example of a situation that requires rigorous triage of people who are injured, in order not to waste the meagre resources available by allocating them to desperate cases. The injured man is in a deep coma and has breathing difficulties. His abdominal haemorrhage has not been able to be controlled by a first operation carried out in a small private hospital in the city. However, an ambulance is evacuating an injured man to Turkey although his chances of survival are extremely low. For the professional, it is a case. For the father at his bedside, it is his son. For the brothers in arms around him, guns slung across their shoulders, he is a hero. For all of them, it is Allah who will decide his destiny. How could the doctor make them understand that in his view, any attempt at resuscitation was probably likely to fail and that he would be better advised to keep the resources he had available for cases with a more positive prognosis?

If medical and health criteria do not always prevail in triage, which others come into consideration? There are some legitimate exceptions to the rule of a fair distribution of care between individuals. For example, we have to recognise that not prioritising care for some leading figures in society would magnify the disaster and the social unrest accompanying it.

More concerning are those circumstances when emergency assistance can also be used to the benefit of partisan interests, for example those of certain combatants or a certain political class. Particular economic interests can also prevail: those of war profiteers in the context of an armed conflict or more generally, those of crooks inside and outside aid organisations, for whom a disaster represents an opportunity to do good business. The study20Garrouste-Orgeas M, Montuclard L, Timsit JF, Reignier J, Desmettre T, Karoubi P, Moreau D, Montesino L, Duguet A, Boussat S, Ede C, Monseau Y, Paule T,Misset B, Carlet J, Predictors of intensive care unit refusal in French intensive care units: a multiple-center study, French ADMISSIONREA Study Group, Critical Care Medicine, 2005 April 33(4):750-5.on selecting patients for admission to an intensive care unit in normal times, however, serves as a reminder that much more common phenomena are always at work. In France, for example, in spite of the existence of precise medical criteria, a request for admission to an intensive care unit has less chance of being satisfied if it is made over the phone rather than as the result of direct physical contact and similarly if it occurs during certain periods of the day.

Setting medical criteria, the organisational constraints imposed on carers and attempts to divert assistance to other (military, political or economic) purposes to one side, patient selection often comes down, in reality, to the ordinary kinds of discrimination commonly found in society and which are drawn from a list that is both traditional and endlessly updated: “... in the name of a symbolic principle that is known and recognised by both the dominant and the dominated, a language (or pronunciation), a lifestyle (or a way of thinking, speaking or acting) and more generally, a distinctive property, emblem or stigma...”.21Pierre Bourdieu, La domination masculine, Seuil, Paris, 1998. p. 8.

The idea of considering individuals as equal, as a matter of principle, during the triage procedure and only distinguishing one from the other according to a small number of defined medical criteria, also has its medical limitations. For example, the consequences of a chest trauma are different based on whether it occurs in a patient who was previously healthy or a patient suffering from a chronic respiratory condition.

In an idealised view of disaster medicine, assuming that individuals are treated equally, the second assumption put forward is the existence of a single cause of harm leading to an inhabitual number of cases of the same kind, differing only in terms of their seriousness. Excess mortality objectivises the geographical dimension of the event and leads to one or a small number of causes of harm giving rise to an epidemic (or traumas, or infections, or deficiencies) related to the type of disaster. If such specific causes of harm did not exist, mortality would be normal.

The return to normal mortality occurs if this very limited number of causes of harm22Or a small number of causes.disappear spontaneously – they can also be controlled by preventive action – or if they can be treated in a way that means they do not lead to fatal outcomes. Identifying cases that are directly related to the catastrophic event and ranking them in order of seriousness therefore lies at the heart of organising an emergency response. The hope that the supply of care can be rapidly adjusted to demand is based on the fact that the small number of causes of harm will make it possible to simplify treatment, which in turn favours a rapid, mass deployment of assistance. A frequent operational error is not to realise that excess mortality is due to a small number of causes and not to focus efforts on dealing with them. Whilst it is legitimate outside of exceptional situations, a relative dispersion of resources to carry out a multitude of tasks leads, in an emergency situation, to a failure to control mortality whilst giving the reassuring impression of an attempt to respond to all the needs covered in normal times.

The idea of a unique cause of harm makes it possible to prepare staff for their task quickly and simply, by distributing triage protocols that are as succinct as possible: very serious cases (code black23An example is the START (Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment) triage protocol, which is based on coding patients by colour from the most to the least serious conditions (black, red, yellow and green).: someone who is dying or dead, an emergency situation that has not been addressed in time, low priority); serious cases (red: an absolute emergency to be treated as a priority); moderate cases: a relative emergency that can wait some time, depending on availability) and non-serious cases (code green, not urgent, could if necessary be sent back home).

Re-establishing the balance between supply and demand for care is achieved at the cost of reducing the variety of clinical scenarios to a small number of categories, based on seriousness, usually two to five depending on the different triage systems. In reality, however, the idea of a single cause of harm has its limitations. For example, two patients with a bullet wound in the same part of their body might, at the precise moment when they come into triage, present in exactly the same way depending on the few criteria selected to decide in a minute where the patient should be sent to, although in reality their prognoses are very different. These depend on which organs the bullet has hit when it entered their bodies. These could be identified through a proper clinical examination but in the usual conditions there is no time to do it.

The supposed effectiveness of interventions (whether they are for diagnostic, preventive or curative purposes) is the main justification for triage procedures. This should be able to be supported by studies carried out in line with current standards of evidence-based medicine. In practice, disaster situations do not lend themselves well to scientific experiments. Behind their apparent rationality, disaster response protocols rely to a large extent on reasoning deduced from physiological knowledge and on clinical know-how acquired through practice. When scientific studies are carried out in spite of the precarious circumstances, their results show the practical limitations of triage procedures.

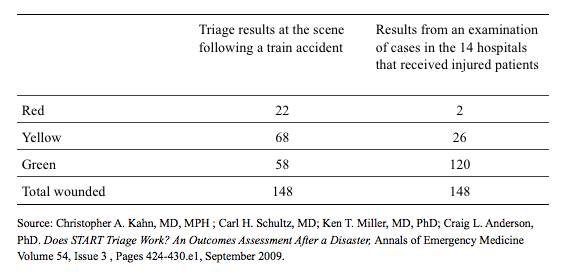

These are the results of a triage study carried out on people wounded in a railway disaster (2003) according to the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) protocol, which has been in widespread use in the USA since the 1980s.

Seventy-eight wounded patients’ order of priority was overestimated and three were underestimated. The triage category of 66 wounded patients was confirmed by hospital data. In this example, triage at the site of the railway accident meant that patients labelled “red” arrived in at the hospitals one hour before the “yellows” and “greens”. Of the 22 patients labelled “red” during triage at the scene, however, hospital data was to confirm that only two were really “reds”.

The example above clearly shows that if the resources available are fairly generous, the professional in charge of the triage process will tend to want to avoid prejudicing the individual in front of them at a given time. The temptation is then, too often, to assign priority to cases whose treatment could be deferred based on a rigorous application of the criteria.

If, on the other hand, resources are very limited, the desire to protect the interests of the wider community prevails. The risk is then that patients are disregarded when they could have been saved had they been seen as a priority. For example,24Observation made by the author when on a field visit. in November 2012, there were numerous cases of acute malnutrition at the health centre in Konseguela (Koutiala district, Mali). Admission to the intensive nutritional rehabilitation programme relied on a triage procedure based on an anthropometric index. This is calculated on the basis of the child’s weight and height, compared with those of a reference population of children deemed to have optimal growth. At the time of my visit, there was a discussion within the care team about a child who was failing to thrive and who had been refused admission. His weight-to-height ratio was equal to the threshold chosen to distinguish moderate cases of acute malnutrition from severe ones. To access the intensive nutritional care reserved for severe cases, the patient must have an anthropometric index not equal to but strictly lower than the threshold value selected. A quick glance at the child and his two brothers and asking their mother a few simple questions, however, made it clear, without using an anthropometric index, that he was in serious need of intensive nutritional rehabilitation. We noted that the child had been denied care because of an imperfect diagnostic test,25André Briend, La malnutrition de l’enfant. Des bases physiopathologiques à la prise en charge sur le terrain, lecture delivered in the context of the Danone Chair 1996, Institut Danone, 1998, p. 35.the anthropometric index, whose use is justified to a large extent for economic reasons. Providing food for all malnourished children would be too expensive. Regardless of its pertinence, the use of an anthropometric index gives the impression that the rationing of therapeutic foods is based on the use of a scientific criterion, namely calculating the ratio of weight to height. Is that enough for people to forget that the decision taken means giving food to one child rather than another even if both of them are effectively skin and bone?

Act

Rationing care to the benefit of some and the detriment of others is often presented in the literature as a source of significant ethical dilemmas. The most frequently cited example is the decision, when there is a massive influx of people who are sick or injured, not to attempt to change the life prognosis of those who are judged to be too seriously ill. Their treatment is reduced to palliative care so that the end of their life is as painless as possible. In reality, the chances of survival of people who are dying, which are poor even in normal times, are appalling once a disaster occurs, because of the precariousness of their living conditions and care. When these types of patients receive medical treatment, the carer’s anxiety has more to do with the difficulty they face in accepting their own powerlessness in light of the scale of the disaster than cruelly exercising power over life and death during triage.

In addition to the dilemmas raised by managing patients with the poorest prognosis, the most disconcerting thing for healthcare workers is the requirement to switch from one set of ethics to another. The first, the set that applies ordinarily, is presented as being centred on the individual interests of the sick or injured patient. When the situation is extraordinary, because demand exceeds supply in a much more marked way than usual, there is a perceived risk of wasting meagre resources and precious time by paying too much attention to cases with too good, or conversely, too poor a prognosis. The ethical approach that is then recommended is described as utilitarian. The objective becomes “the greatest good for the greatest number”, to the point where a small number of individuals are sacrificed for the general interest. The tension between individual interests and the collective interest is already present outside exceptional situations, in the routine administration of care. But events that are seen by society as disasters give an unusual degree of visibility to discrimination in access to care, which is ordinarily more readily accepted because it is lost in the banality of day-to-day living.

When demands are numerous and pressing, how is it possible to prevent parsimonious distribution of aid that has been confined to a few priorities from causing too much tension or even violence? The explanation given by carers to justify the choices made in triage is expressed in terms that emphasise that not everyone will be treated in the same way but that it will reduce the number of deaths across the population as effectively as possible. Believing that such a justification will be acceptable to an individual in distress is based on the hypothesis that they will bear their suffering patiently for the good of the many. Experience shows that invoking the collective interest is not always sufficient to calm either people in a precarious situation, or those close to them. The use of – at best dissuasive – force is often inevitable, for example to prevent a pharmacy or food warehouse being pillaged by an angry crowd of people who have been deprived of goods that are essential for their survival. In this sense, an emergency operation is successful when it results in exceptional social and political mobilisation that is capable of producing a consensus in terms of the distribution of aid and care, in order to prevent social and political unrest on too large a scale.

Triage is thus shown to be what it is in essence: an essential stage in an operation based on rationing and the maintenance of order. Once it is seen as an affirmation of a new social norm of distributing scarce resources, triage becomes meaningful and useful: “Strictly, a norm does not exist: it plays a role, which is to devalue existence to allow it to be corrected.”26G. Canguilhem, Le normal et le pathologique, P.U.F., 2009, p. 41.

Before they reach the stage of triage with individuals, aid workers focus the distribution of aid on certain situations and certain populations. Analyses of aid policies become more accurate when they no longer confine themselves to identifying their beneficiaries but also those who are denied access to care and assistance. Who are they? Why are they not a priority and what are the consequences of this choice? Were other choices possible? When and how might changes in the situation mean that they could be included in care?

Every operation bears the mark of one or a small number of people who have controlled the distribution of care and assistance. They play their role best when they bear in mind that triage is not simply a technique but also marks the switch, for better or worse, from one form of distributive justice to another. The new norm is not there to be followed blindly but to serve as a pointer towards the creation of an aid policy that changes every time, in order to respond as effectively as possible to an exceptional situation and the specific needs of its victims.

- 1. Observations gathered by the author, as a member of the back-up team for the mission.

- 2. Emergency Situations Working Group – Transmissible diseases: surveillance and action, WHO Americas Regional Office, WHO office in Haiti, Évaluation des risques pour la santé publique et interventions. Séisme : Haïti, January 2010, p. 14 Pan American Health Organization. Pan American Sanitary Bureau, Regional Office of the World Health Organization, Establishing a mass casualty management system, Washington, D.C., 2001

- 3. Florian Cabanes, Pratique de l’anesthésie réanimation en situation précaire: Analyse d’une mission humanitaire avec MSF à Haïti lors du séisme du 12 Janvier 2010, medical thesis / speciaist subject anaesthesia and resuscitation, University of Paris VI, 15 October 2010.

- 4. MSF, Haiti earthquake response / Inter-sectional review / Executive report / Synthesis of six specific reviews from 12th January to 12th April 2010, 2010, Geneva.

- 5. Kenneth V. Iserson and John C. Moskop, Triage in Medicine, Part I: Concept, History, and Types, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Volume 49, no. 3: March 2007.

- 6. The rest of this article will focus on the response to inhabitual deaths for the purpose of simplification. The same arguments would apply to functional deficits that are not life-threatening, for example the loss of the use of an eye, hand or speech, a persistent disabling pain, etc.

- 7. Cour des comptes, La politique vaccinale de la France, communication à la commission des affaires sociales du Sénat, Paris, October 2012.

- 8. Richard D. Knabb, Jamie R. Rhome, and Daniel P. Brown, Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Katrina 23-30 August 2005, National Hurricane Center, 20 December 2005.

- 9. Institut National de la Statistique Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances, Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples, Niamey, Niger, 2006.

- 10. The destruction of property is not analysed in this article.

- 11. http://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicateur/SP.DYN.CDRT.IN

- 12. Interpreting and using mortality data in humanitarian emergencies. A primer for non-epidemiologists, Francesco Checchi and Les Roberts, Overseas Development Institute / Humanitarian Practice Network, network paper number 52, September 2005, London, p. 7.

- 13. Mzia Turashvili and David Crémoux, Review of the OCA Emergency Intervention in Liben, Ethiopia. Evaluation report, September 19th to November 15th, Vienna evaluation unit, MSF internal report, 2012.

- 14. http://www.msf.org/article/ethiopia-surge-number-somali-refugees-demands-increased-capacity

- 15. Denis Hémon and Eric Jougla, Impact sanitaire de la vague de chaleur d’août 2003 en France. Bilan et perspectives - Octobre 2003. Rapport remis au Ministre de la Santé et de la Protection Sociale. INSERM and Institut National de Veille Sanitaire, Paris, 26 October 2004.

- 16. http://www.indexmundi.com/g/g.aspx?v=26&c=bc&l=fr

- 17. Dr Michel Nahon, Les principes généraux de la Médecine de Catastrophe, SAMU de Paris, lecture on emergency medical assistance, Université Paris V, January 2011.http://www.urgences-serveur.fr/IMG/pdf/princip_cata_s.pdf

- 18. Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, Mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagnes, Tome IV, J. Smith, Paris, 1817, p. 487.

- 19. Author’s observations during a field mission in August 2012.

- 20. Garrouste-Orgeas M, Montuclard L, Timsit JF, Reignier J, Desmettre T, Karoubi P, Moreau D, Montesino L, Duguet A, Boussat S, Ede C, Monseau Y, Paule T,Misset B, Carlet J, Predictors of intensive care unit refusal in French intensive care units: a multiple-center study, French ADMISSIONREA Study Group, Critical Care Medicine, 2005 April 33(4):750-5.

- 21. Pierre Bourdieu, La domination masculine, Seuil, Paris, 1998. p. 8.

- 22. Or a small number of causes.

- 23. An example is the START (Simple Triage And Rapid Treatment) triage protocol, which is based on coding patients by colour from the most to the least serious conditions (black, red, yellow and green).

- 24. Observation made by the author when on a field visit.

- 25. André Briend, La malnutrition de l’enfant. Des bases physiopathologiques à la prise en charge sur le terrain, lecture delivered in the context of the Danone Chair 1996, Institut Danone, 1998, p. 35.

- 26. G. Canguilhem, Le normal et le pathologique, P.U.F., 2009, p. 41.

To cite this content :

Jean-Hervé Bradol, “In a disaster situation: get your bearings, triage and act”, 3 avril 2020, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/natural-disasters/disaster-situation-get-your-bearings-triage-and-act

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute