Vanja Kovacic

Vanja Kovačič

Introduction

The intention

This book is a result of my three-year collaboration with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), or Doctors Without Borders, a medical humanitarian organization. MSF, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999, places its primary focus on the delivery of emergency aid and works under the maxim “alleviate human suffering.”

I was not new to MSF. In 2010 I joined the organization to conduct anthropological research focused on access to care for HIV patients in Kenya (Kovačič and Amondi, 2011a; 2011b). When I was contacted again in 2017 by MSF’s CRASH unit (Centre de Réflexion sur l’Action et les Savoirs Humanitaires) – the internal body engaged in critical reflection on field practices – I realized the significant nature of the project being proposed. As a medical anthropologist I would be given the unique opportunity to carry out independent research centred on MSF’s Reconstructive Surgery Programme (RSP) for the victims of war in the Middle East.

Working as an anthropologist in the humanitarian field, I would be joining a group of authors who have critically examined humanitarian practice, including those researching MSF. The importance of such study had already been discussed in publications such as “Medical anthropologies. Ethnographies of practice” (Panter Brick and Abramowitz, 2015). But the proposed research into the RSP, rather than being principally occupied with its political or institutional structure, required me to design an exploration of the microcosm of relations among humans who, like me, shared a time and space influenced directly or indirectly by the experience of war. To look at this microcosm meant uncovering the layers of what it means to be human in the context of war. And I was offered the exceptional chance to look at the worlds of both war victims and humanitarian workers. I readily accepted the challenge. The resulting study, presented here, is unique among critical anthropological studies of humanitarian aid.

My work differs from the extant critical ethnography of aid in a number of ways. Principally, it focuses on the relationships, tensions, and negotiations between patients and their social environment, including their medical environment, rather than critiquing institutions, structures, and power relations. In addition, unlike the authors who have examined political economy, structural violence, or critical humanitarianism (Mosse, 2004; Mosse and Kruckenberg, 2017; Farmer, 2001; 2006; Fox, 2014; Redfield, 2013), I do not use a critical lens per se. I maintain an observational stance, open to interpretation. The book is written in a narrative style, rich with the voices of the participants, who highlight, in their own words, the authentic world they are describing.

With regard to those who write on the anthropology of war from a theoretical perspective, this book speaks to the “experimentalists” (McCutcheon, 2006; Schröder and Schmidt, 2001). These theorists view war violence as something that has a basic impact on life, which they say can only be grasped through the individual’s experience. With Reconstructing Lives I have not taken a theoretical standpoint. But my unique anthropological lens acknowledges the physical, economic, psychological, social, and symbolic types of violence that are in line with the experimentalists’ view. This was my framework when I developed my research model, and this was my guide as I wrote the book you hold in your hands.

My work documents the daily reality of patients in hospital and after their return home. I also researched and recorded the experiences of the people who treat them. The overarching goal of the research was to contribute to knowledge that might establish a more holistic approach to rehabilitation – one that could make adjustments for a patient’s long-term needs. I wanted to develop a new way to look at patients by describing their daily lives during and after rehabilitation, to respect them within their own reality, and to involve them in their own care and reconstruction of their lives.

Bearing this in mind, I did not focus only on the delivery of medical care. The book describes Syrian and Iraqi war victims. Their journey starts with an injury, continues through the improvised medical treatment in their home countries, leads them to the MSF-run hospital in Amman, Jordan, and ends with their return home. Along the way, individuals attempt to pick up the pieces of their previous lives, add new elements from their treatment and travel experiences, and finally establish a new, reconstructed reality. I explore how the MSF staff and their patients interact and how this interaction contributes to the immense task of healing that awaits the victims of war. The reader visits the intimate spaces that usually remain closed to the outside observer: the interior of the MSF hospital and the interiors of the patients’ homes. Both spaces are rich with human contact, perceptions, emotions, conflicts, and reconciliations. The struggle of the individual to overcome visceral reactions that result from seeing injured bodies, the need to follow social and institutional norms, and that to keep ethical dilemmas in check have a tangible impact on both patient and medical worker.

Reconstructing Lives marks yet another departure. As a reminder of the severe personal and social consequences of war, its main “actors” are the permanently injured – too often the silent survivors of war. One of them is Ismael, whose story we get to know. Reconstructing Lives gives Ismael a voice and unlocks the link between resilience, self-interest, and survival. It presents the perspective of a patient’s own reckoning with the rehabilitation process and its aftermath. The book’s findings move our understanding beyond medical rehabilitation alone, to grasping what is involved in the rehabilitation of an individual’s emotional, symbolic, spiritual, and social existence.

The MSF-run RSP has been providing care for neglected war victims for over a decade, and the book captures a part of their cumulative experience. We will explore the political and organizational context that led MSF to open the RSP in Amman. The book’s first chapter explains in detail the anthropological research that resulted from my being embedded in the RSP from April 2017 to December 2018. Chapter 2 then explores the relationships between patients and hospital staff and the staff’s perceptions of patients. Chapter 3 looks at the patients and their personal and medical histories before they entered the RSP, and Chapter 4 uncovers the patients’ own perceptions of the programme. In Chapter 5, patients’ descriptions of their daily lives after they have returned home are presented along with reflections on how the RSP has influenced them. I conclude in Chapter 6 with a description of research reflexivity and a discussion of the broader areas of support needed for victims of war and other patients who struggle to become a viable part of society.

Ismael, one of the many war-injured

It was 6 April 2012. About 20,000 soldiers invaded the neighbourhood near Ismael’s home. Mortars started shelling. Ismael was in the house with some men who had attempted to rescue injured people from under the collapsed houses. An explosion hit the house in the early afternoon, and he was among those who were injured by shrapnel. His leg was wounded. In a panic, another injured person unintentionally trampled over his thigh and completely fractured his femur. His leg was now dislocated, and it moved like the leg of a puppet.

His friends evacuated him by placing him on a door used as a stretcher. The street was under sniper fire and mortar bombardment. In the surrounding area, holes were opened in the walls to allow passage from one house to another more safely. Ismael and his rescuers managed to get into a car and a tank shell barely missed them. They arrived at the first-aid post sheltered in a school. Desks had been replaced by beds. Basic medical supplies were missing; pieces of fabric replaced compresses.

Soon after, he was attended in another makeshift hospital, where he was cared for by a car mechanic, who, in the dire context of war, was acting as a nurse. His wound was sutured even though it was still filled with dirt, and this contributed to the development of infection. Everyone was quite aware that this was the likely outcome, but nobody was able to prevent dangerous infections under those conditions.

The next day, Ismael’s relatives brought him to a governmental hospital in Homs, quite far from his neighbourhood. The road was extremely dangerous. The vehicle zigzagged to avoid being hit. Dead bodies were lying all over the streets. It was said about that journey that “the one who comes out alive had his mother praying for him.” The driver and all the passengers had to duck their heads to avoid bullets along the way. Ismael was hidden in the back of a Škoda mini truck, under a tarpaulin.

The vehicle’s passage over a bump caused Ismael’s fractured limb to shift. It took them an hour to correctly realign it. On the way, Ismael was transferred into a Red Crescent ambulance and he fainted before arriving at the hospital. He woke up when he was taken out of the ambulance. A nurse told them that a security official was tracking them. Fortunately, the regime’s soldiers had not stopped the ambulance in which they were travelling. Because of their wounds, they were wanted men. Due to the fear of arrest, they had less than an hour inside the hospital. After the X-ray, Ismael was taken to the operating room. Under local-regional anaesthesia, the surgeon inserted an external fixator, a set of metal pieces, into the bone, to maintain the alignment of the two bone segments of the fractured femur.

Ismael left his hometown, Homs, to seek treatment in a hospital in the suburbs of Damascus, thinking he would be safer there. Upon arrival, he was again housed in a school that had been transformed into a care centre. The doctor there was injured himself, so he was replaced by an electrician who acted as a nurse. Regardless, Ismael felt that he did a better job than the trained hospital staff. Ismael’s wounds were severely infected by then. The stitches had opened, and pus was flowing out. In the hospital, the cleaning and excision of dead tissue began. He finally received an intravenous injection against infection. He remained in that hospital in the suburbs of Damascus for six months.

The area was subsequently bombed. Tanks fired more intensely than Ismael had ever seen before. The hospital was hit. Civil defence evacuated him, and Ismael found himself in the street leaning on his walker to run away. While on the run, he had to crawl for over two kilometres to escape. His wounds reopened. All roads were blocked by the regime’s forces and he could not go back to the hospital.

Ismael decided to settle in a location controlled by the regime’s forces, but he could only stay in the area by hiding in holes or under stairs, living in constant fear of missile fire. By luck, he met persons with the necessary security clearances able to take him to a doctor. He was unable to lean on his injured limb. The doctor was an elderly man who had worked in Gaza (Palestine) and who advised him to abandon his walker and to start using a wooden stick instead. This helped him regain some ability to walk.

At this point Ismael decided to leave Syria. It took him a month and a half to reach Jordan. On the way, the regime’s soldiers shot and killed two members of the group travelling with him. But this was not the end of the tragedies. Upon arriving at the border, Jordanian border guards were welcoming. But they would not let a man enter the country alone, without his relatives. Entire Syrian families at the border at the same time as Ismael who tried to enter the country without the required documents suffered the same fate and were denied asylum. When they were turned away, the Syrian border guards opened fire. Five families were killed, and Ismael joined others in burying them on the spot. The survivors found refuge in a mosque where Ismael – by his own description – spent one of the worst nights of his life.

Finally, Ismael managed to enter the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. He spent two weeks there but was unable to get treatment because of long wait times to access care. He left the camp to take a job as a baker in Jordan, work that required him to stand twelve hours a day. The pain was so severe that one day he collapsed. His wounds opened again, and the infection resumed. Friends informed him about a hospital in Amman where a team of Médecins Sans Frontières was working. Ismael talked of a suspension of misery upon entering the MSF hospital. It was where his definitive treatment began.

Surgical care for the neglected war victims

Ismael’s story is comparable to that of hundreds of thousands of civilians in the contemporary Middle Eastern conflict. Though these individuals may never have participated in combat,In fact, even if they were previously on the battlefield, an injury or their capture places them in the category of “non-combatant” in the eyes of international humanitarian law (ICRC, 2019). Hence, they have the same rights to the medical assistance as anyone else but rarely have access to it.they are nevertheless bombarded, hunted down, tortured, and executed. These survivors of war violence emerge physically and emotionally affected. In the societies where they live, they are not recognized as war invalids. Indeed, this definition is reserved for wounded war veterans. Those who are recognized as wounded war veterans have access to specialized medical care and, to a certain extent, social and economic support. In this way, the society communicates their recognition of the ultimate sacrifice they have made in the name of their countries/political groups (Blanck and Song, 2002). The civilians injured in war, however, experience hardships similar to disabled veterans but are forgotten when it comes to any benefits. They remain an unnoticed and ignored part of society.

War takes an undeniable toll on civilian lives. Civilian deaths in the current conflicts in the Middle East number in the hundreds of thousands. For instance, the Iraqi Body Count,Their records are drawn from cross-checked media reports, hospitals, morgues, NGOs, and other official reports.thought to be the world’s largest public database of violent civilian deaths, estimates that since 2003 over 205,000 deaths have occurred. Between January and February 2019 alone, over 500 civilian deaths were reported in Iraq (Iraq Body Count, n.d.).

The number of fatalities since the beginning of the war in Syria is equally high. In December 2018 the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR, 2018) reported 111,330 civilian casualties, including 20,819 children under the age of eighteen and 13,084 women over the age of eighteen. In Yemen the reports are sporadic, and the figure most often cited by politicians and the media is more than 10,000 deaths,The underestimation of the number of deaths due to war violence is, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED, 2019), fuelled by all parties involved in pro-regime and anti-regime coalitions to avoid public pressure.a serious underestimation. All these figures are approximate, since the records of war casualties often do not count the dead and wounded unless they are military personnel (SOHR, 2018; Iraq Body Count, n.d.; ACLED, 2019).

We can only assume that the count of bodies that have been deformed by war-related injuries should be far greater. The lack of accurate records is a real problem. Even for wounded military personnel, the count of injuries is not straightforward. Categories such as “died of wound,” “survived and evacuated,” or “slightly injured” (and returned to duty), do not count those injured in an accident, nor those with less severe injuries not treated in a medical facility (Bellamy, 1995). In sum, war victims are frequently counted only as those who have lost lives. The numbers who survive but are permanently damaged – physically, emotionally, or socially – remain undercounted.

In the humanitarian field, wars are considered the ultimate source of human suffering, and war surgery has always been an integral part of humanitarian practice (Giannou et al., 2013). The war situation is sometimes called an epidemic of injuries due to the sharp increase in trauma cases compared to peacetime (Bellamy, 1995). War wounds, with related extensive tissue destruction and contamination, are wholly different from routine emergency trauma care (Giannou et al., 2013). This is not surprising considering that there is a constant race between new sophisticated armaments, whose sole purpose is to effectively destroy human bodies, and the surgical advancements necessary to manage increasingly severe wounds.

In fact, military surgery has contributed to the development of surgical practices and knowledge since the beginning of human warfare (Pruitt, 2006). Military personnel are predominantly treated in military hospitals placed close to the battlefield (Gawande, 2004; Pruitt, 2006; Potter and Scoville, 2006). Civilians and combatants who no longer participate in hostilities, may receive surgical care in improvised local medical structures, at the medical facilities of organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) or its partners, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (Giannou et al., 2013), or with organizations such as MSF (Trelles et al. 2015).

For trauma victims in war, medical studies have established that lifesaving first aid must be delivered within the first hour after the injury or the chance of survival for the critically wounded becomes increasingly reduced (Bellamy, 1995). In addition to the time it takes to reach emergency care, the site of the wound is also of great importance for the chance of survival. The sites where the most fatal injuries occur are the head and chest. For non-fatal injuries, seen mainly on patients who survive the transport to a medical facility, the most common location of injuries is on the extremities, particularly the legs. Superficial wounds on skin and skeletal muscles are often in the non-fatal group as well (Champion et al., 2003).Such injuries are also the most common among patients in MSF hospital in Amman.The characteristics of modern arms are responsible for this typical distribution of injuries, with most injuries being of a penetrating type caused by fragments from explosive devices, such as shells and grenades. Burn, blast, or bullet injuries are much less common today than they are in the historical data compiled in past wars. The causes of injuries to civilians are similar. The ICRC hospital in Kabul recorded that the highest proportion of admitted civilians was injured by fragments and mines (Coupland and Samnegaard, 1999).

Despite similar causes of injuries, the severity of combatants’ and civilians’ wounds and their follow-up surgical care differ. An analysis of the Emergency Management Centre in Erbil, which received the injured from the battle for Mosul in Iraq between 2016 and 2017, focused on the epidemiology of war-related injuries among patients (Nerlander et al., 2019). Of 1,725 total patients included in the study, 46% were civilians. Civilian patients were more than twice as likely to have injuries to their abdomens and six times more likely to undergo amputations of their limbs than combatants. Authors noted that civilian injuries were due to the lack of ballistic protection, and that their need for surgical care was more intense than combatants’.

War surgery is predominantly emergency care. Surgeries are often performed with limited resources under improvised conditions. Proximity to the battlefield, staff fatigue, overwhelmed hospital facilities, disruptions in electricity, water, and medical supplies, and the unpredictability of events make the delivery of surgical care extremely challenging. The mass casualties in war are also far greater than and radically different from those in civilian practice. ICRC, for instance, reports on the war triage category of “leave to die in dignity,” a category non-existent in ordinary emergency practice (Giannou et al., 2013). The triage protocols are often applied to “save life and limb for the greatest number with the least possible expenditure on time and resources” (Giannou et al., 2013: 10). Severe injuries and suboptimal medical care leave many survivors of war permanently disabled. Sophisticated techniques that could diminish or possibly eliminate the effects of disability cannot be performed under field conditions. And such techniques as those required in reconstructive surgery can usually only be delivered later in referral hospitals.

During the years-long armed conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, such specialized referral hospitals have been scarce or non-existent, and they may lack surgical equipment and personnel. Patients who have undergone surgical procedures under improvised conditions not only often suffer side effects from the field surgeries: they are often left without support for their physical, emotional, and social recovery. For veterans of combat, rehabilitation is provided in their own country, which, however, despite technological advances, is not always satisfactory (Messinger, 2009). For war-injured civilians from the countries participating in war, such care is simply non-existent. MSF is one of the few organizations that offers specialized surgical care and rehabilitation for survivors of war in the Middle East. The programme – the RSP – is located in a specialized hospital, the Al Mowasah hospital, in Amman. It has been in operation for over ten years. But before we go deeper into the programme details, let us explore what motivated MSF to focus on the provision of war-related surgery.

A brief history of MSF’s surgical practices

Surgery has been a medical specialty practised by MSF since its creation in 1971. In its early days, due to a lack of resources and expertise, MSF’s contribution to the provision of surgical care took the form of assigning surgeons to other aid or public health agencies such as ministries of health, faith-based institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Frères des Hommes, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (Rigal and Dixmeras, 2011).

In the 1970s, however, MSF pursued its ambition to carry out surgical activities autonomously in Lebanon (1976) and Chad (1979) (Bradol, 2011). The value of humanitarian surgeons sent from abroad into an emergency context was soon questioned by the field teams themselves. In organizing a response to natural disasters – for example, earthquakes, floods, and hurricanes – the field staff were often faced with restricted access to the affected sites, particularly during the initial emergency phase. Their delayed arrival on the scene greatly reduced the possibility of preventing death through surgical intervention (Brauman and Vidal, 2011).

There were exceptions – for example, during the earthquakes in Pakistan (2005) and Haiti (2010), where, due to the nature of local construction, many victims were injured by concrete blocks or large stones. Even after the acute emergency phase was over, a large number of victims who survived needed orthopaedic surgeries over the long term – a call to which MSF responded.

MSF soon recognized that surgical assistance to refugee populations was a more efficient use of its resources compared with responding to so-called natural disasters. In the mid-1980s MSF offered surgical care to refugees in Sudan, Zaire, and Uganda.

The increase in surgical activity also caused MSF to become the subject of internal and external criticism due to the lack of quality in the care they were able to provide. The brisk rotation of the expatriate surgeons, lack of standardization of surgical protocols, and inefficient recruitment of patients came under a critical lens. MSF responded with an attempt to professionalize its surgical activities, which led to surgical training for a number of the foreign general practitioners working for MSF. These trainings were first conducted in 1984 during field missions in Uganda and Sudan and were later repeated in Zambia. The concept of the doctor-surgeon was not foreign to the countries where MSF worked, such as Sudan and Colombia, as in those places basic surgical procedures were performed by non-specialists, such as general practitioners.

As the surgical needs at MSF field missions increased, MSF responded by increasing the number of its field staff who were trained but were not formal specialists in surgery. Foreign doctors from the “rich countries” were often associated with colonialism, and the fact that they were often underqualified created embarrassment for MSF. A discussion was sparked within the organization to begin providing surgical training for general practitioners in the countries where MSF had missions. In this spirit, MSF devoted six years to the school of anaesthetist nurses in Phnom Penh, Cambodia (opened in 1991 as a joint collaboration between MSF, the Ministry of Health, and the French universities Paris-Nord and Bordeaux), and opened a surgical training project for Ethiopian doctors in Weldiya (1993).

Parallel to the attempts to improve the surgical skills of its staff, MSF continued to deliver surgical care for the war-wounded. Following an example from the ICRC, MSF settled along the borders of countries at war to attract the wounded from the areas of conflict. For instance, from 1983 on, the wounded in the Tigray People’s Liberation Front were transported from Ethiopia to Sudan, where MSF treated them. Staff mostly received cases suffering open fractures on limbs, and the discussions on how best to treat them were lively. This was an opportunity for MSF to make choices and to take a step towards the standardization of care. For example, the use of external fixators for such injuries was introduced as a standard around this time.

The opportunity to further develop field surgical practices arose with the civil war in Sri Lanka. By 1986 four surgical programs had been opened by MSF to replace the shortage of local surgeons, who had, particularly if they were Tamil, fled the country. Each year dozens of foreign surgeons were sent to Sri Lanka to care for the war-wounded amid a population of about 1 million people. Until the year 2000, when the peace agreement was signed, MSF collected vast experience managing surgical activities. Both the scale and the duration of the surgical programmes in Sri Lanka created a favourable framework for major developments in anaesthesiology and operating-room management. Thereafter, surgeons sent to the field were systematically accompanied by an anaesthetist (nurse or doctor) and an operating-room nurse.

MSF also started to move closer to the frontlines of war, particularly in urban areas. Examples of such missions are Somalia (1991), Bosnia (1992), and Rwanda (1994). Exposure to recently injured patients caused an evolution in MSF field surgical practice. MSF introduced complex procedures, such as abdominal, orthopaedic, or vascular surgery, which are usually reserved for specialist surgeons.

There were also improvements in logistical supply links that allowed for a better response in surgical situations. During the genocide of Rwandan Tutsis in 1994, for instance, MSF deployed Kit 300, which consisted of the medical materials for 300 surgical interventions. The kits, which were designed by Jacques Pinel in 1990, were compact, so that their transport was simplified, and they could be carried to the field in two pickup trucks. This was essential for providing a rapid response in the context of genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda. This logistical innovation further contributed to the standardization of surgical practices as well as to the efficacy of MSF’s relief activities (Vidal and Pinel, 2009).

From the 2000s on the focus of MSF was to improve the quality of surgical care, to lessen the gap with the care provided in countries that do not lack resources. Recruitment of surgical referents – specialist advisors providing technical support to their counterparts in the field missions – at headquarters, systematic use of staff specialized in anaesthesia, generalization of recovery rooms, focus on pain management, and design of “clean” hospital structures were just some of the actions undertaken. Since the mid-2000s the organization has revolutionized the effectiveness of rapid response by developing an entire hospital structure under inflatable tents. The inflatable hospitals were successfully used in Pakistan in 2005 and in Haiti in 2010.

To improve the quality of care, MSF looked at US trauma centres. Those centres had experience with bullet-related injuries from urban violence, and they had the advantage of providing care in a stable context, quite unlike MSF. The idea was to go beyond the usual objectives of humanitarian surgery, which at that point were almost exclusively aimed at the survival of the injured person, by reducing as much as possible the patient’s loss of function over the medium and long term.

Missions such as those at Port-Harcourt, Nigeria, and Port-au-Prince, Haiti, were examples of the intention to adapt trauma-centre protocols to the humanitarian context, and to focus more on improvements in the functional impacts of trauma. The traditional traction suspension (a set of mechanisms for aligning up broken bones) to manage lower-limb fracture was replaced by osteosynthesis (metal implants surgically inserted into the bones to repairing the fracture). This practice reduced hospitalization times and gave better functional outcomes to patients. The use of osteosynthesis was unusual in humanitarian settings due to the need to provide high levels of hygiene. MSF was concerned whether they could ensure sufficiently sterile operating theatres under unstable field conditions. This led to the introduction of field microbiology labs to monitor the spread of infection, particularly those that were hospital acquired and resistant to antibiotics.

Ultimately, all this knowledge in surgical care that MSF accumulated was reflected in the MSF RSP in Amman, the longest-standing MSF surgical programme to date.

The origins of MSF’s RSP

The origins of the RSP have a unique and complex background that is, to a certain extent, still reflected in today’s programme. In 2003, after the attack and invasion of Iraq by a US-led military coalition, working in that country became increasingly dangerous for international humanitarian organizations. Difficulties accessing this population dated back more than twenty years to the time of the Iran–Iraq war (1980–1988). The establishment of an embargo (1990) and the international military offensive in response to the invasion of Kuwait (1991) only served to exacerbate the lack of access. The embargo continued until 2003, and the new US-led invasion in March 2003 took the situation to new, nearly impossible levels. Previously, Saddam Hussein’s regime had invited a large number of aid agencies into the country to help alleviate the health consequences of the embargo. In March 2003 the invasion of the country by foreign forces only strengthened the resolve of humanitarian workers to carry out activities in Iraq. But their enthusiasm was short-lived. On 19 August 2003 a truck full of explosives detonated at the UN headquarters in Baghdad killing 22 people. While the UN primarily had a political role, several of its agencies were essential to humanitarian work (UNHCR, World Food Programme (WFP), United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO)). Two months later, also in the capital, the ICRC suffered a bomb attack in which two people died. As humanitarian workers considered the future of their activities in the country, these crimes were on everyone’s mind. In the small world of international aid to Iraq, Margaret Hassan was an important figure. She was Irish and had lived in Iraq for decades. She was an Arabic speaker and a head of the local branch of Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE). Her pleasant personality was the subject of the broadest consensus. No one imagined that she would be kidnapped and executed. But in November 2004 that is exactly what happened. Even radicals, including the leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq, called for her release. Circulation of the shocking video showing her execution struck aid workers with profound alarm.

It became clear that no one was safe from kidnapping and attack except, perhaps, in certain areas of Iraqi Kurdistan. MSF decided in 2005 to withdraw its teams from all other areas of Iraq. But the interest in providing humanitarian aid to Iraqis remained.

The resumption of contacts with Iraq and the start of the RSP occurred in a roundabout way. The MSF team and the surgical team of the Iraqi Medical Association (IMA, the equivalent of the National Order of Physicians in France) met in Pakistan, where they were responding to surgical needs after an earthquake in 2005. What was eye-opening to MSF representatives was how Iraqi doctors collaborated, regardless of their political or religious affiliation. This collaborative spirit was unique at the time, in a context in which sectarian and violent political groups of all persuasions were rapidly emerging. The friendliness and group cohesion of the Iraqi doctors remained unchanged by the situation in their own country, where military and militiamen were systematically entering hospital rooms to finish off the wounded and attack health workers.

Iraqi representatives initiated a discussion on how surgical support could be provided in Iraq by MSF, and two possible avenues were discussed. The first was the improvement of emergency-room competence in general in Iraq by establishing a steady flow of supplies and ongoing training of staff. These adjustments were essential because of the huge increase in injured people that Iraqi hospitals were receiving at the time due to mass-casualty events. But the ambition was greater than that. Since the patient profile was made up of those with severe functional deficits, those involved in the discussions thought that long-term care was key. Extended treatment beyond emergency care was needed, and the idea of specialized reconstructive surgery hospital was born. The two teams left Pakistan committed to keeping in touch in the hope of achieving collaboration on this objective in Iraq.

Figure 1. The RSP cornerstone meeting. An illustration showing the meeting between representatives of the IMA and MSF, which was a cornerstone of the MSF RSP in Amman.

The actual implementation of the plan was not far behind. It began in June 2006, in Amman, with a round of discussions and negotiations initiated by MSF. The Jordanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Jordanian Red Crescent, the IMA, and the Iraqi Ministry of Health all participated along with MSF. For MSF, the aim was to obtain the agreement of the Jordanian and Iraqi authorities to open the RSP. Once an agreement was signed allowing MSF to start its activities in Amman, including expediting visas for injured Iraqis to come to Jordan for treatment, MSF’s specialized RSP hospital opened in 2006 utilizing operating rooms and hospital beds rented from the Jordanian Red Crescent. Initially, the RSP only received the injured from Iraq, but later, after violence erupted during Arab Spring (2011) and in other ongoing or new armed conflicts, patients from Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Palestine also started to arrive.

The RSP today

The RSP is currently run in Al Mowasah hospital in Amman. Some of the surgeons who participated in the initial brainstorming in Pakistan are still there. The programme performs specialized orthopaedic, plastic, and maxillofacial surgeries, often on patients who suffered severe injuries years before their entry to the hospital. They have lived with different levels of disability or post-surgical complications and upon arrival at the MSF hospital some cannot walk or stand up. Some cannot speak or chew food, or their skin is so contracted due to burn scars that they are unable to move their hands or neck.

Besides numerous complicated anatomical deformities, many patients also suffer from infections that occurred when dirt and other infectious material penetrated the wounds together with the shrapnel or bullet. Such infections – common among patients at the RSP – are extremely persistent, causing severe pain and potentially threatening life (Fily et al., 2019). For instance, in the study of 727 patients examined for infections at the RSP, over 70% were positive and over 80% of those were infected with bacteria resistant to many ordinarily available antibiotics. Bacterial resistance is a global problem and, for the type of infections seen at the RSP specifically, extremely costly antibiotics are needed. It is not surprising that a large part of the RSP budget is allocated to cover the cost of antibiotics. In the patients’ countries of origin it would simply be impossible for the health systems, already weakened by war and conflict, to afford such specialized, expensive treatment.

Often, numerous surgeries are needed to clear tissue that is no longer vital due to infection, to fix bones in their correct positions and extend them where necessary, to transplant skin and muscles, or to reconstruct missing noses, fingers, or jaws. Surgeries are typically followed by intensive physiotherapy, during which patients who suffer amputations also must learn how to use artificial hands or legs. Patients in the hospital are also treated by psychologists and psychiatrists, who offer individual or group sessions to reduce the impact of psychological disorders and to help them deal emotionally with the challenges associated with life in a hospital setting.

Undergoing several surgeries and participating in post-surgery rehabilitation means that patients’ treatment in Amman is lengthy, ranging from a couple of months to over three years. And it is not only the processes in the hospital that are long: the preparations for a patient’s arrival in Amman can take months. Doctors known as medical liaison officers (MLOs) work in Jordan, Iraq, and Yemen, where they register patients in need of surgical care. Through their contacts in local hospitals, refugee camps, and through their personal social networks, they identify patients with specific surgical needs. The patient then provides medical reports and X-rays, which are sent to Amman to be reviewed by the surgical committee. This committee, during weekly meetings, discusses potential cases and gives the green light to those whose injuries that could be improved by one of the surgical interventions offered at the RSP. The planning for a patient’s departure from their home then starts, and the MLOs assist them with administrative work to obtain visas and arrangements for their flights to Amman. Once the patient arrives in Amman, they reside either in hotel rooms rented for them by MSF or in the hospital. Each patient also receives a daily per diem for expenses. Those patients who have severe mobility limitations or who are children are accompanied by a carer, usually a family member who also receives accommodation and a per diem.

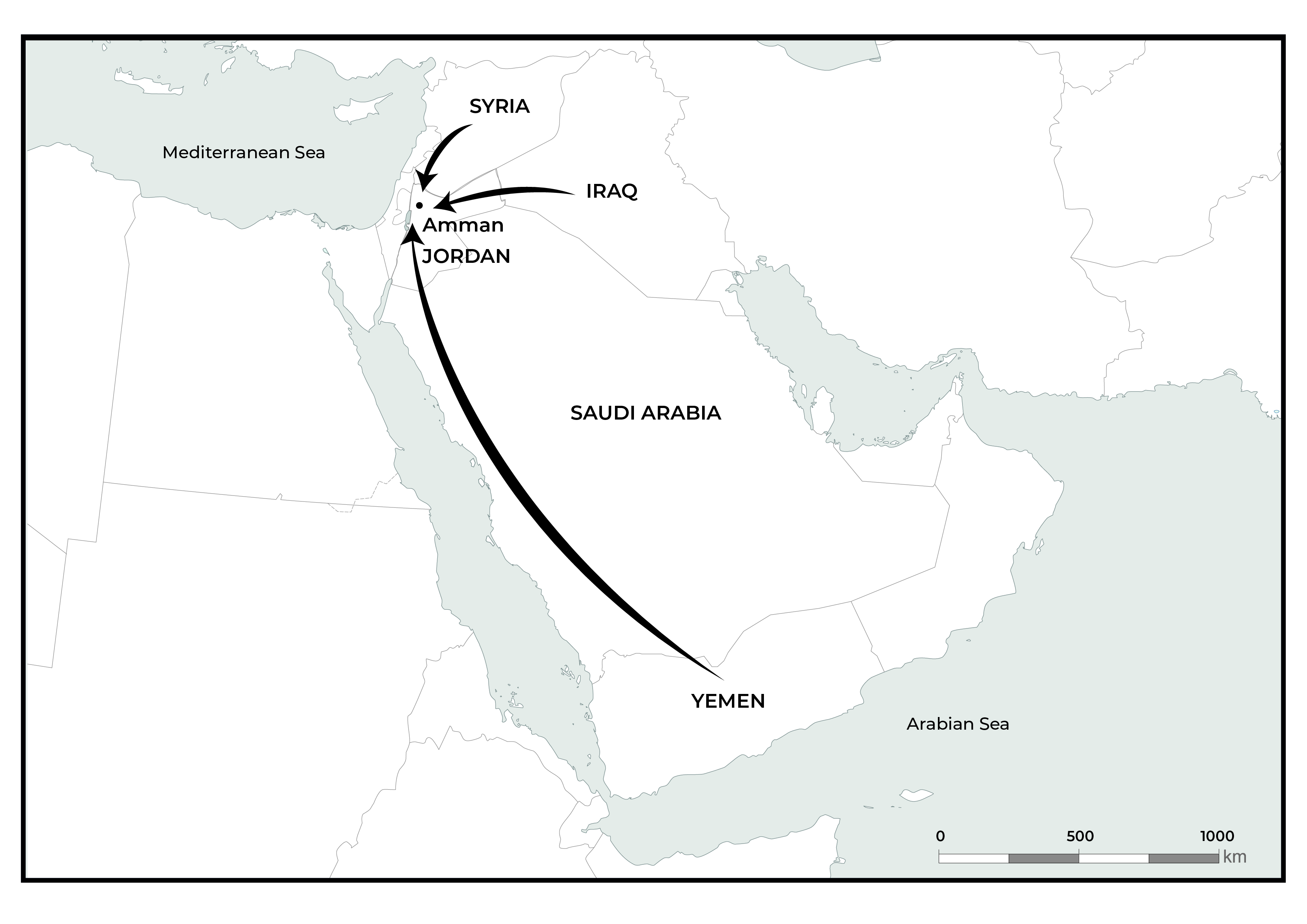

Figure 2. The RSP operational area map. A map showing the countries from which patients travel to Amman (indicated by arrows) to receive treatment in the RSP hospital.

There are exceptional aspects to the MSF RSP. First, the types of surgery are focused entirely on functional improvements for patients who have extremely complicated medical profiles. They are not considered lifesaving. Management of such complex surgical cases is considered extraordinarily taxing even in hospitals around the world with the best technical and human-resource capacity (Fakri et al., 2011). The daily work of surgeons in Amman is often characterized by innovation, since there are no established surgical protocols to guide the interventions in such complicated medical cases.

Second, the long-term rehabilitation of patients, delivered away from their home countries, creates a special kind of healthcare setting. Also unique is MSF’s comprehensive social support for the patients and their carers. Furthermore, surgical care is delivered by surgeons originating from the patients’ home countries, creating a bond between patient and surgeon. Surgeons’ long-standing presence in the RSP is also vital for building up and maintaining their surgical skills – skills that are geared to such specialized circumstances. Their knowledge can potentially be transmitted back to the medical systems in the countries affected by war.

Third, the scale of the programme and the treatment provided to injured non-combats makes the RSP unique not only in the MSF framework but also in the global landscape of war surgery (Hornez et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2016). The treatment is delivered free of charge and targets patients who would otherwise be medically neglected. Finally, the durability of the programme provides an opportunity for extensive research that can make a contribution to scientific literature.

All of these aspects provided the time and space necessary for the comprehensive anthropological fieldwork I carried out in Amman and that I present in the following pages.

Période

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed about our latest publications. Interested in a specific author or thematic? Subscribe to our email alerts.