Dying for humanitarian ideas: Using images and statistics to manufacture humanitarian martyrdom

Michaël Neuman

This article has been inspired by an analysis conducted by MSF-Crash of humanitarian security management and why and in what ways it is evolving. We endeavour not only to describe humanitarian imagery, but to analyse its consequences - the risks it generates for aid workers operating in perilous situations.

Most reflections on humanitarian imagery have focused on the image of the victim, notably its use in media campaigns which, since the beginning of the 20th century, have been designed to generate emotion and hence actionSee Christina Twomey « The incorruptible Kodak: Photography, Human rights and the Congo Campaign », Liam Kennedy and Caitlin Patrick (dir.), The violence of the Image. Photography and International Conflict, I.B. Tauris, London, 2014. or the recurrent depiction of the dominant-dominated / saviour-victim relationship. Indeed, there has been much criticism of aid agencies’ marketing campaigns that, as Emily Baughan noted,Emily Baughan, A short history of helping far off peoples, 12 November 2015, http://africasacountry.com/2015/11/a-short-history-of-helping-far-off-peoples/ confine assisted populations to the status of victim. In protest against this paternalist tradition of humanitarian imagery (we had to wait until the end of the 2000s to see anything other than a photo of a young black victim being cared for a white care-provider on the cover of MSF’s international reports), humanitarian communication is now being parodied, as noted by historian and Eleanor DaveyEleanor Davey, Fact, Advocacy, Parody, 7 July 2015. https://aidhistory.wordpress.com/2015/07/07/fact-advocacy-parody/

in recent articles. More recently still, the historian Benjamin Thomas WhiteBenjamin Thomas White, Images of Refugees (parts 1 to 3), see https://singularthings.wordpress.com has focused on the imagery of refugees - especially the images produced by journalists and aid workers -, highlighting their ahistorical and homogenising nature. But in this article we are more interested in the image of the aid workers themselves.

This article has been inspired by an analysis conducted by MSF’s Centre for Reflection on Humanitarian Action and Knowledge (MSF-Crash)Sincere thanks to the whole MSF-Crash team that took part in the collective analysis of security management which allowed me to write this article, and to Bertrand Taithe and Eleanor Davey of Manchester University’s Humanitarian and Conflict Research Institute for their input and references. The title of this article – « Dying for humanitarian ideas » – has been borrowed directly from Bertrand Taithe, with his authorisation. See Bertrand Taithe, « Mourir pour des idées humanitaires : sacrifice, témoignage et travail humanitaire, 1870 – 1990 », in Caroline Cazanave et France Marchal-Ninosque (dir.), Mourir pour des idées, Presses universitaire de Franche-Comté, Besançon, 2009. of humanitarian security management and why and in what ways it is evolving.See also the book that came out of it: Michaël Neuman and Fabrice Weissman (dir.), Saving lives and staying alive: Humanitarian security in the age of risk management, London: Hurst and Co., 2016. We endeavour not only to describe humanitarian imagery, but to analyse its consequences - the risks it generates for aid workers operating in perilous situations. We draw on research that retraces the different stances on security adopted by Médecins Sans Frontières over the years, and examine how the production of images and statistics and the normalising of security management, appears to have contributed to towards rehabilitating the idea of acceptable humanitarian sacrifice.

Sacrifice as an integral part of a missionary-cum-humanitarian moral system

To talk about aspiring to death and humanitarian missions in the same breath might seem incongruous in the extreme. Yet, the history of missionaries attests to a strong relationship between humanitarian engagement and risk-taking, danger and death. Not only did the Christian missionaries - come to save souls and spread civilisation - live with the threat of death, not only did they not flee death, at times they appeared to be seeking it. Humanitarian assistance at the end of the 19th century served as a justification (and also a motivation) for missionaries, with martyrdom as an integral part of their moral arsenal. Southern Algeria, Tonkin and China all offered real opportunities to die for religious and humanitarian ideas.See Bertrand Taithe, op. cit. These deaths were testimony to the value of the work undertaken. The martyrs set the example for future missionaries, and a culture developed in which the culmination of their mission was death. In this sense, the ideal of sacrifice could be interpreted as a suicidal attitude.

Martyrdom of Saint Pierre Borie in 1838 in Vietnam

Source: Wikipedia

Yet this attitude cannot be put down to antiquated acts of faith, as the quest for martyrdom was still very much alive in missionary orders right up to the 1950s, and was present –although more discreetly so - in the new rhetoric on risk-taking in the decades that followed.

Thus, a colleague of two missionaries executed in Laos in 1961 wrote: “They were all admirable missionaries, willing to make any sacrifices, living in great poverty and with boundless devotion During that troubled period, we were all to some extent seeking martyrdom, wishing to give our lives for Christ. We were not afraid to risk our lives, we were all committed to helping the poorest, visiting the villages, caring for the sick and preaching the gospel…”http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/13038/Bienheureux-No%EBl-Tenaud.html

The rejection of martyrdom and the preservation of the hero figure

Like the rest of the modern humanitarian movement in the West, the organisation Médecins Sans Frontières, of which the author of this article is a member, is in part an emanation of this missionary tradition. But it is equally a product of a lay tradition, that of the Red Cross, drawing on the imaginary world of adventure and common law. As Bertrand Taithe writes, “the figure of the heroic explorer standing alone in the face of great danger is prominent among the key humanitarian leaders of the late 19th century”Bertrand Taithe, « Danger, risk, security and protection: concepts at the heart of the history of humanitarian aid», Michaël Neuman and Fabrice Weissman, Saving lives and staying alive. Humanitarian security in the age of risk management, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2016.. For MSF, which was founded in 1971 in the wake of a conflict in which propaganda and image played a major roleOn this subject, see also the Journal of Genocide Research, volume 16, Issue 2-3, 2014, devoted to the Biafra conflict, for a very thorough analysis., martyrs gave way to heroes – primarily theatrical heroes.

MSF’s founders, including Bernard Kouchner, saw themselves as adventurers. In a book of interviews with the Abbé Pierre, published in 1991, Kouchner has no trouble assuming this personal quest, with a mixture of snobbery and frivolity. Humanitarian assistance became a byword, the rallying cry of a young generation eager for discovery: “Let’s offer adventure to the world’s youth, and elegance. There is an aesthetic dimension to humanitarian assistance - a certain panache!”Bernard Kouchner, in Abbé Pierre and Bernard Kouchner, Dieu et les hommes, Robert Laffont, Paris, 1993.

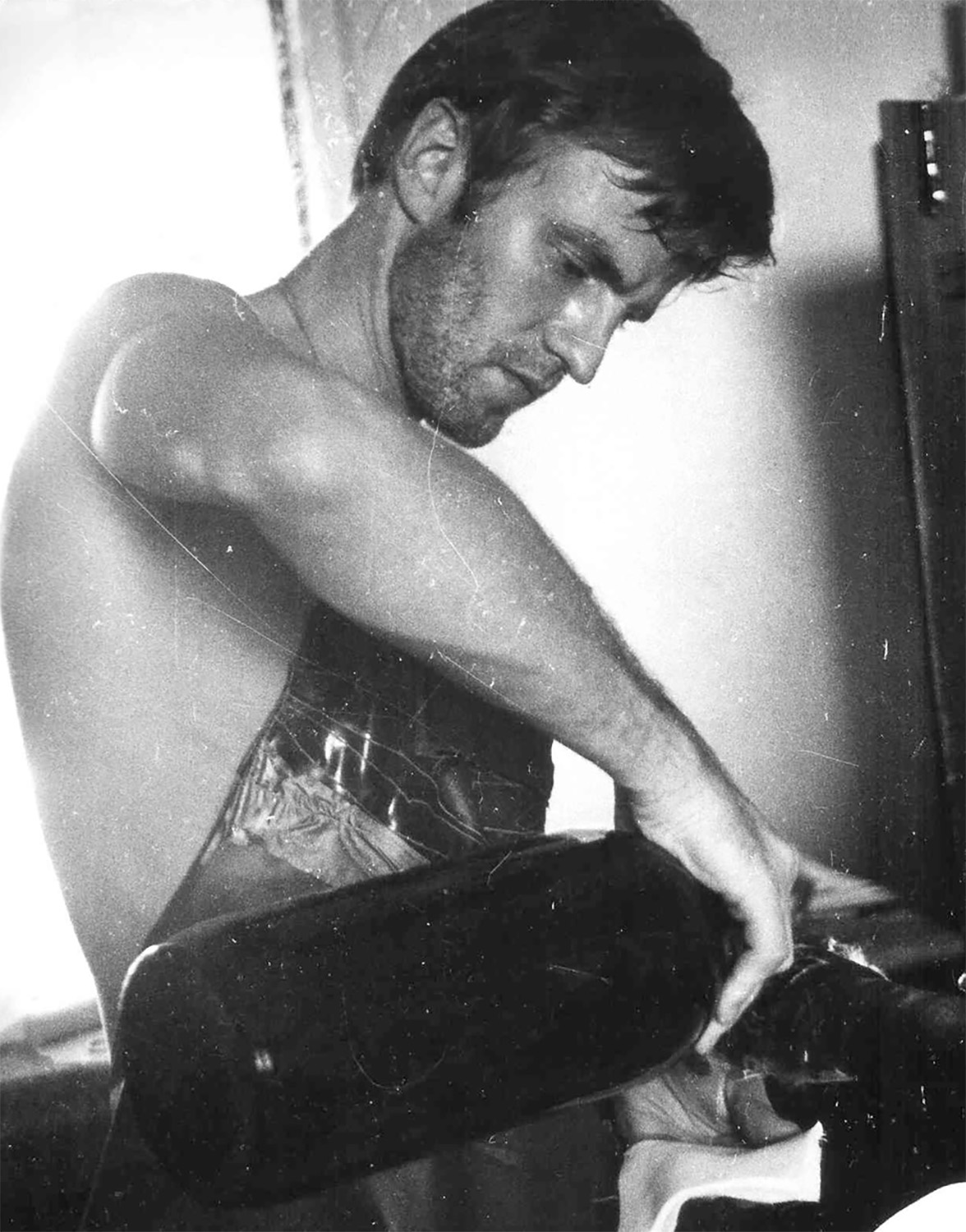

This romantic interpretation, tinged with selflessness and even arrogance, is reflected in the organisation’s first charter which stipulates that; “anonymous and volunteers, [its members] seek no individual or collective satisfaction from their activities. They understand the risks and dangers of the missions they carry out”.MSF’s current charter, dating from 1992, maintains this paragraph in slightly modified form. The founders of Médecins Sans Frontières, most of them marked by their experience with the Red Cross in Yemen or Biafra (Nigeria) in the 1960s and conscious of the dangers involved, maintained - for the most part - a certain lyricism. The members of the nascent organisation played up the confrontation with danger, a confrontation that illustrated the “aristocracy of risk” – another of Bernard Kouchner’s expressions, for whom, “it’s much more fun to take a bullet between the eyes while playing Lawrence of Arabia than dying of cirrhosis at Bercy”Bernard Kouchner, in Abbé Pierre et Bernard Kouchner, Dieu et les hommes, op.cit., p. 21.. Thus certain images of the pioneers bore a striking resemblance to photos of Hollywood stars.

Bernard Kouchner

Source: Lutecium

Burt Lancaster in “From Here to Eternity”

Source: Google images

After the departure in 1979 of many of the organisation’s founders, and of Bernard Kouchner in particular, the flamboyance, the "hero-making" aspect of MSF's rhetoric remained. But this playing up of the danger was accompanied by an explicit refusal of sacrifice. In 1982, the then president confirmed: “No-one is asking us for heroics; just to do our jobs the best we can, in the most humane way possible and - above all - to come back in one piece”.Annual report for 1981 presented at MSF’s Annual general meeting in 1982

So MSF’s first years were marked by rhetoric that focused on the engagement of its personnel. Despite the many security incidents, security was not a subject as such. The public image projected by MSF, whose “fame” took off at the end of 1970s, was defined by its own depiction of its activity - the doctor bringing relief to the victim – usually African. The humanitarian doctor is not political.

The mid-80s saw an historic initiative to raise funds for the victims of the famine in Ethiopia. On 13 July 1985, in the midst of the disaster, the singer Bob Geldof, appointed himself as representative of western conscience, bringing together some of the world's best-known performers for a dual venue charity concert held simultaneously in London and Philadelphia. One of these performers was David Bowie who gave a breath-taking version of his song “Heroes”:

We can beat them

Just for one day

We can be Heroes

Just for one day

David Bowie, Live Aid 1985

Source: Digital Spyuk

In the end, the “hero” was as much David Bowie as the humanitarian doctors, or as the millions of television viewers who watched the event broadcast live worldwide and who could, with a cheque or bank transfer, help save a piece of humanity. Indeed, the hero figure is a handy invention. Not only does it create consensus, portraying a western world happy to bring relief to the third worldThe « White savior » narrative, it provides a way of disregarding the political dimensions of a crisis, even a phenomenon as unnatural as the Ethiopian famine in the 1980s (we know how much it owes to the Ethiopian authorities’ forced relocation policySee Laurence Binet, Famine and forced relocation in Ethiopia, 1984 – 1986, “Speaking out case studies” series, MSF, 2013.). After all, heroes are not fallible; they don't make mistakes. They are not involved in politics. They save.

As mentioned earlier, it is thanks to hero figures that the aid agencies of the 1980s gained in notoriety, in social standing. Aid workers became heroes not because they were prepared to face dangers, but because they went places where others – all those sitting at home in front of their television sets - didn’t (to use one of the classics of Médecins Sans Frontières’ communication).

Médecins Sans Frontières communication campaign, 1985

Source : INA

The 1990s were particularly traumatic for aid agencies. The conflicts they felt they understood, corresponding as they did to an East versus West-type logic, were replaced by crises of a new complexion - more complex and more vicious. The succession of extreme crisesSee Marc Le Pape, Joanna Siméant and Claudine Vidal (dir.), Crises extrêmes. Face aux massacres, aux urgences civiles et aux génocides, Paris, La Découverte, 2006 in West Africa, the Russian Caucasus, the African Great Lakes region, Somalia, ex-Yugoslavia, etc., the scaling up of resources for a rapidly expanding “aid industry” and the increasing number of serious security incidents affecting aid personnel triggered new awareness of the need to protect not only civilian populations, but also the security of aid teams.

Martyrdom redeemed?

When the anthropologist, Jean-Pierre Albert evokes heroism in his article for "La Fabrique des Héros [The Hero Factory]”, he does so in the following terms: “Heroism is not linked to the outcome of an undertaking, but to the acceptance of risk and suffering, and even death"Jean-Pierre Albert, « Du martyr à la star. Les métamorphoses des héros nationaux », Pierre Centlivres et al., La fabrique des héros, Paris : Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 1998. : it’s John Wayne at the Alamo, or Che Guevara in Bolivia. The hero is thus a person who braves death, and martyrdom is simply the most evidentiary manifestation of heroic virtue. So, when in the second half of the 2000s, hero figures returned to the stage, they were no longer the ones who save. They had become, in an increasingly threatening world, the ones who brave dangers and, of course, bring relief –sometimes at the cost of their own life.

This redefining of the contours of humanitarian assistance took place in the early 2000s in the context of the "war against terrorism” following the September 11th attacks on the United States.

Humanitarian exceptionalism

A tragic event played a particularly important role in this redefinition. In August 2003, 22 people, most of them United Nations employees, perished in an attack on the UN building in Bagdad. As much as the event itself, it was the death of the head of the mission, Sergio Vieira de Mello, a charismatic Brazilian diplomat, that signalled the start of this new era - one in which aid workers appear to have become the victims of choice of armed groups of all kinds.

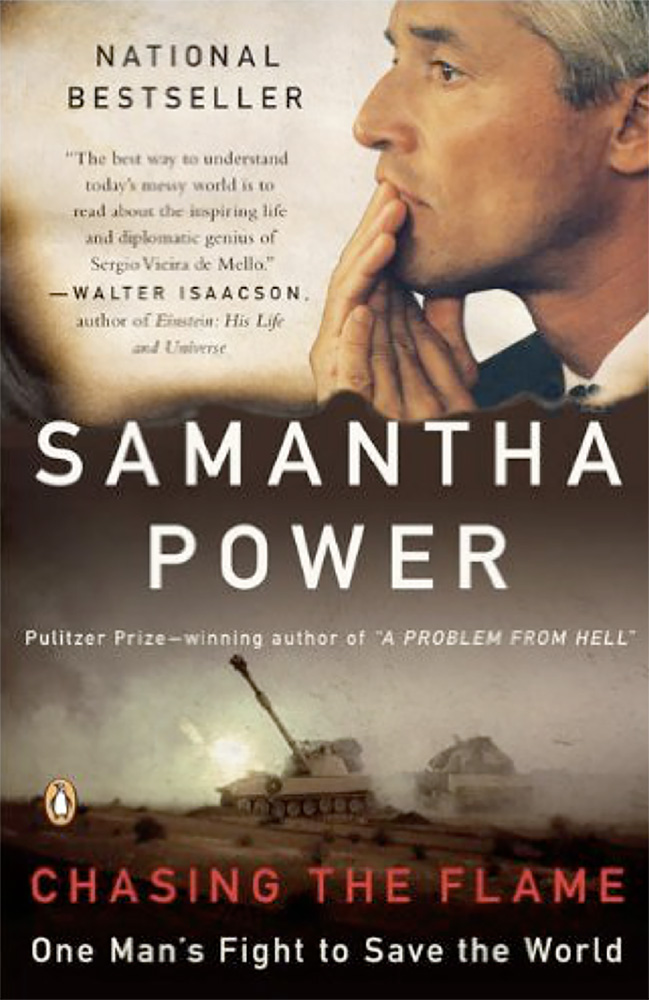

Samantha Power, current US ambassador to the United Nations, devoted a book to Vieira de Mello in 2008, humbly entitled, « Chasing the Flame: One Man’s Fight to Save the World ». In 2009, the biography was made into a film by the American cable channel, HBO, in which the “hero” had all the attributes expected of the modern humanitarian hero: attractive, something of ladies’ man, brave, self-sacrificing, a conveyor of democratic ideals…

Cover of Chasing The Flame: One Man’s Fight to Save the World, written by Samantha Power

Source: Penguin Random House

Although the death of Vieira de Mello did not trigger all the changes that would affect the imaginary world of humanitarian aid, it was clearly a turning point. In any case, this was the context in which a victimist approach developed, based on images and statistics intended to illustrate how the world was becoming an increasingly dangerous place.

The deadly attack on the United Nations headquarters in August 2003 and that against the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICFC) in October of the same year were seen as emblematic of an unprecedented increase in deliberate attacks against aid workers. Such fears were heightened by the difficulties encountered by relief organisations in the Middle East and the Sahel due to the expansion of radical Jihadist groups and the recurrence of kidnappings for ransoms. Whereas in the 1990s, the increase in attacks against aid workers was put down to the deliberate targeting of civilians in conflicts, as the 2000s got underway, talk was of the deliberate targeting of “aid workers as such”.

Thus was born the concept of « humanitarian exceptionalism » - to use the terminology of the researcher Larissa FastLarissa Fast, Aid in Danger. The perils and promise of humanitarianism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2014.-, illustrated - among other things - by the launch in 2008 of World Humanitarian Day, or WHD, to pay tribute every 19 August - anniversary of the attack against the United Nations in Baghdad – to « those who face danger and adversity to help others »See http://www.un.org/en/events/humanitarianday/.

The twitter hashtag that accompanied the 2014 WHD campaign, #humanitarianhero, came in a variety of versions, all converging to manufacture the perfect humanitarian hero, whether civilian or military, as United Nations peacekeepers were also credited.

Source: Impact Magazine

Source: Twitter

This 2.0 humanitarian hero who braves terrible danger has in some cases been literally subsumed into the category of superhero. The traditional unequal relationship between saviour and victim is thus replaced by a hero with the victims nowhere in sight. On 17 June 2015, London’s Evening Standard published an article with the evocative title: Dfid’s CHASE team: meet the unsung superheroes of the civil servicehttp://www.standard.co.uk/lifestyle/london-life/dfid-s-chase-team-meet-the-unsung-superheroes-of-the-civil-service-10325729.html. The article paints the portrait of seven members of the British government’s aid agency, the “Chase team”, attributing them – without any obvious trace of humour – with superhuman powers. Parody vies with reality.

Source: Static Standard

Statistics to the rescue of humanitarian exceptionalism

At the start of the 2000s, and increasingly so from 2005-6 onwards, statistics played a major role in the portrayal of aid workers as humanitarian heroes by evidencing how dangerous the world was becoming. Questionable at many levels, especially with regard to the methodology they draw onSee Fabrice Weissman, « Violence against aid workers: the meaning of measuring », Saving lives and staying alive. Humanitarian security in the age of risk management, CNRS Editions, Paris, 2016, statistics offer the advantage of legibility. However, the briefest examination of these statistics undermines the image of an increasingly dangerous world in which aid workers are particularly vulnerable.

Although, in absolute terms, the average annual number of victims has quadrupled over the last fifteen years, in relative terms the number is remarkably stable: the rate of aid workers killed, injured or kidnapped varies between 40 and 60 for 100,000 and between 1,997 and 2,012 per year. In other words, the increase in the number of victims is proportional to the increase in the number of aid workers. So, there is no evidence that humanitarian action is more dangerous now than in the past. The risk of violent death would even seem to be decreasing, if we are to believe the decline in the percentage of deaths among the victims of attacks.

Yet statistics support rhetoric that is as depolitized as it is anhistorical, helping to transform aid workers into victims of the forces of evil. They thus contribute towards a victimist narrative that recounts the violence done to aid workers and turns them into heroes and martyrs of today's wars. This dramatization is strengthened by the introduction of norms and procedures that tend to deprive aid workers of “a sense of engagement in dangerous situations, while their employers put numerous procedures in place to protect themselves from legal and reputational risks in case of accidentMichaël Neuman and Fabrice Weissman, « Introduction », in Saving lives and staying alive. Humanitarian security in the age of risk management op.cit..”

Source: Aid Worker Security

Memory and martyrdom

This contemporary portrayal of humanitarian martyrdom can be seen in the recent erection of monuments dedicated to aid workers and in the campaigns promoting their protection.

In this respect, Canada is a pioneer, as it erected the Monument to Canadian Air Workers back in 2001.

Monument to Canadian Aid Workers

Source: Dominique Marshall

In 2013, Australia followed suit, erecting a monument to the glory of its aid workers fallen on the field of honour, and Great Britain joined them in 2014, by adding aid workers to the categories of “innocent victims” to which a memorial stone of the same name is dedicated outside Westminster Abbey. These monuments are still quite scarce, but the decision to incorporate aid workers into national architecture bearing a strong resemblance to war memorials for dead combatants is not as “innocent” as all that. By analogy with these dead combatants, we could conclude that memorials to dead aid workers are as much intended to honour the memory of the deceased as to prepare new generations for future losses.

Memorial for Humanitarian Aid Workers

Source: Remembering Humanitarians

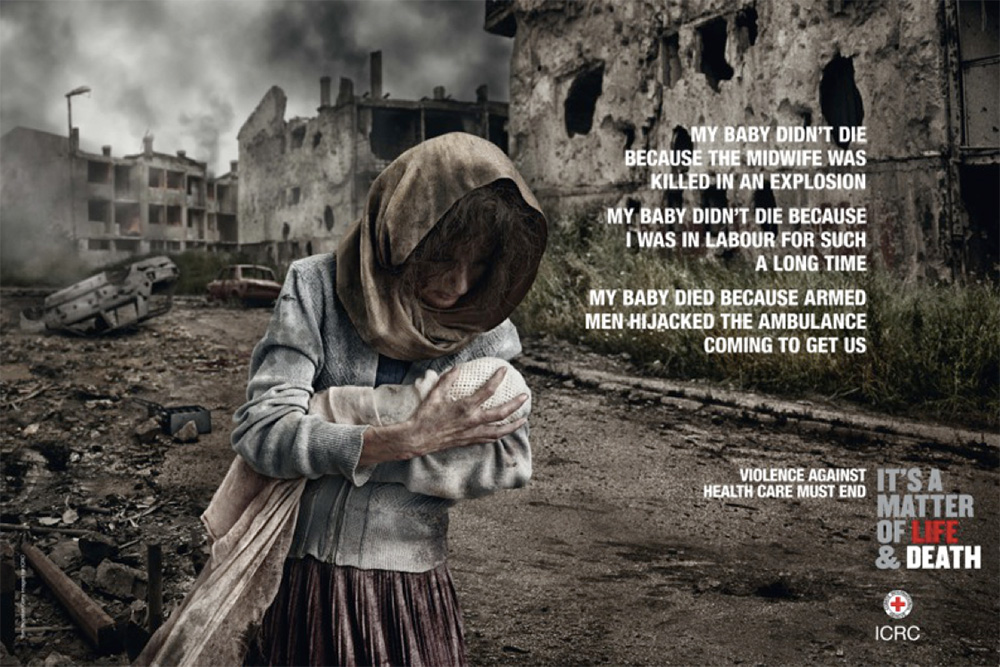

Whereas the Canadian initiative illustrates a long-standing concern for the security of aid workers and is part of longer history of spotlighting the deaths of aid workers, the British and Australian monuments reflect an acceleration of this phenomenon - much strengthened by the emergence of campaigns for the protection of aid workers, such as the ICRC’s “Health care in danger” campaign, and Action against Hunger’s “Protect aid workers" campaign.

Based on the premise that violence against aid workers is increasing, these initiatives set out to denounce it - without always specifically denouncing those who commit it. They often bear all the hallmarks of contemporary marketing. The two above-mentioned organisations have launched poster campaigns in the Paris metro, where the general public is made to witness to the violence done to “aid workers” or “health workers”. Humanitarian victims become the victims among the victims. They become heroes without ever having to justify the usefulness or the value of the work accomplished, while the guilty parties are relegated to an abstract image. And what is more, the visual identity of the image chosen by the ICRC has strong religious overtones: is this a madonna offering herself up to the gaze of passers-by?

Source: Saddington Baynes

***

Hashtags, opinion campaigns, monuments…, humanitarian imagery is diversifying to offer, alongside the traditional images of victims of epidemics or countries at war, images of saviours-cum-victims. Yet, in truth, this seems to have resulted more in the self-intoxication of the milieu itself than to a change of attitude – more compassion – on the part of the public for the professionals of the aid sector. After all, aren’t aid agencies producing these images essentially for themselves?

Although we would all prefer to die a hero rather than a victim, the heroising of aid workers raises at least two problems. The first is that it produces a being set apart from the rest of the human race – better, more worthy. The second – and the most problematic for the professional sector we are concerned with here – is that treating aid workers like heroes can also lead us to believe that death is an integral part of the system, an occupational hazard. It seems to us that this is where the real danger lies: setting sacrifice up as a virtue within a sector that has made “humanity” one of its cardinal principles.

To cite this content :

Michaël Neuman, “Dying for humanitarian ideas: Using images and statistics to manufacture humanitarian martyrdom”, 15 février 2017, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/humanitarian-actors-and-practices/dying-humanitarian-ideas-using-images-and-statistics-manufacture

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute