Vanja Kovacic

Vanja Kovačič

2. In the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital

In this chapter we will follow patients and staff through their daily routines at the MSF hospital so that we can discover the unique texture of life in the RSP in Amman. We will examine the relationships that develop between patients and their healthcare providers and conclude by recounting the widespread perceptions staff have of their patients. In the end we will see that in many ways these perceptions conflict with the patient-centred approach which drove this research and which MSF seeks to achieve.

Daily life in the hospital

Al Mowasah hospital is an impressive-looking five-storey building located in the popular market area of Amman, called Marka. Entering through the automatic sliding glass doors reveals the first surprise: there is an absence of an emergency atmosphereAs the part of legal requirement in Jordan, the hospital has an equipped emergency room. Emergency cases managed at Al Mowasah hospital, however, are rare. and the hospital feels unexpectedly quiet. Especially in the morning hours, the feeling of calm is palpable; a few patients might be moving through the hospital lobby on crutches and wheelchairs, a couple of members of staff might be getting coffee at the mostly empty cafeteria, or a group of nurses might be chatting in the hospital corridor.

As the day progresses the atmosphere becomes slightly livelier. Groups of patients might be sitting in the outdoor area, chatting and playing table games. Or there may be children chasing cats and playing in the outdoor playground, with women sitting on the nearby benches and observing them. Never was the sense of tranquillity interrupted. On quiet afternoons staff pass the time in their hospital offices, and patients relax in the outdoor hospital space.

The life of the patients and staff seemed to be comfortably routinized: morning ward rounds, physiotherapy sessions, patients being rolled in and out of the OT (operating theatre), outpatient consultations, activities in the psychosocial department, and time spent in the cafeteria during lunch hours. Occasionally this routinized daily life in the hospital is disrupted by the arrival of new patients, visits from external journalists, volunteers, or MSF representatives. Or there are small conflicts among patients, celebrations of religious days, or gatherings organized for the departure of patients, which bring some liveliness to the usual quiet of the hospital day.

Figure 5. The entry to the RSP hospital.

Another surprise was that the world of the hospital employees and patients merges in mutual informal interactions. This was particularly obvious in the hospital cafeteria, which offered a rich environment for observations. The cafeteria is a large open space on the ground floor that is furnished with colourful tables and chairs and provides a relaxing environment for both patients and staff, who frequently share the space. To make it even homelier, the cafeteria manager knows everyone’s coffee preferences and serves them without needing to hear their order. Patients and their caregivers often join the table where staff members sit, and informal chatting takes place.

Patients sometimes wandered on to the first floor where my office and the OTs were located. They would come to talk with a member of staff such as the pain nurse or nursing supervisor, who were next to my office. Sometimes the patients would just come to greet anyone whose office door was left ajar. Paediatric patients soon started treating the hospital as their home, and, despite rules against it, everyone’s mood lifted when the children made their rounds in the offices, taking pens, drawing pictures, and chatting or playing football in the hospital corridors. I was sometimes invited into this informal merging of the two worlds by patients approaching me for a chat or offering me a sweet, female patients greeting me by kisses on my cheeks, or paediatric patients inviting me to play with them. Patients do not wear the usual institutional hospital clothes but are dressed in clothes that they bring from home or receive as donations in the hospital. Sometimes they looked so familiar and confident within the hospital environment that I would have to ask if they were members of staff or patients.

Figure 6. Patient in the hospital room, seated on the hospital bed.

An extension of hospital life takes place in the Karamana hotel, where patients who stay in the RSP for extended periods are accommodated. One floor of the hotel is permanently rented for MSF patients, and an MSF van travels between the hotel and the hospital to bring the patients back and forth for treatment. Life in the hotel appears even less institutionalized than in the hospital. On a usual day, patients rest in shared rooms watching TV; some go shopping at the local markets, some perform their prayers in the spacious area between hotel corridors, and some cook in the shared kitchen. Like in the hospital, the general sense of slow motion and ease is palpable among the residents, for whom the hotel is their second home.

Unique relationships between patients and their carers

The atmosphere inside the hospital is also characterized by the unique relationships that develop between hospital staff and patients. These dynamics were not obvious at the first glance, but over time, in observations and interviews, the hospital staff revealed what drove these distinctive interactions. Let us examine the details.

Figure 7. The hospital’s outdoor area has a playground for paediatric patients.

As mentioned, the hospital staff and patients feel a strong sense of informality and general friendliness. It was not uncommon, for instance, to see patients interacting with surgeons outside of the consultation room, at the cafeteria or in the hospital corridors. The way patients refer to surgeons is “doctor” followed by their first names. Depending on the surgeon’s personality, this relationship has more or less closeness and informality. The surgeons who were more extroverted often joked with patients, shook their hands, tapped their shoulders, or kissed paediatric patients on the forehead. Patients generally seemed at ease and relaxed during medical rounds with these surgeons, and I did not observe any reluctance to speak directly to them. Those surgeons who were more reserved had less interaction time and fewer verbal or physical gestures of communication with patients, but patients who were more confident and extroverted themselves managed to gain the attention of surgeons in spite of a surgeon’s communication style. Hence, the relationships were generally characterized as an interplay between personalities of all types on both sides.

The relationship between nurses and patients seemed to be even more relaxed, light, and filled with humour. Nurses called patients by their first names, and as soon as they entered a patient’s room they heard complaints about hospital food, wishes to be discharged soon, worries about a patient’s family, and so on. Sometimes the patient–nurse boundaries were blurred, and it seemed that both parties were willing to participate in this. For instance, I observed a nurse throwing a role of gauze at a young male Iraqi patient and laughing out loud during the surgical round. On another occasion, a female patient asked to try on the nurse’s lab coat, which was allowed without any reluctance.

Figure 8. The interior of the hotel. The part of the hotel where patients are located as they wait for their surgeries.

When talking about their relationships with patients, hospital staff generally described them as “unique,” and many participants, including those from non-medical departments, such as administrators and members of the logistics department, referred to the patients as “family” or “friends.” Nurses in particular warmly described how they relate to the patients. “Yes, we [nurses] develop quite personal relationship [with patients] – I think because they need it,” commented one of the nurses (P10, nurse, female (F)). Another nurse was similarly open about her personal approach, “Other than the professional relationship, it is a sibling relationship” (P11, nurse, F). Administrative staff were also informal: “The relationship between us is not like hospital employee and patient: it’s like friends and family” (P58, administration and management, M).

Some individual patients receive an even greater share of attention, and nurses in particular develop a strong sense of attachment to them. This aspect became obvious when one of the paediatric patients, a boy with a lively personality, left the hospital. One of the expatriates described the boy’s character: “He had like really personal way about him and something that a lot of people found kind of magnetic. And as a result, you know, people became quite fond of him, myself included. He was just, really, like a special kid” (P41, administration and management, M). A sense of sadness prevailed along the hospital corridor on the day of his departure. One of the supervisors, who also reported being emotionally touched, tried to motivate his staff to move on. He reported to me about it:

When he [gives patient’s name] left, everybody was crying, even though he wasn’t finally discharged [he is coming back to the hospital]. I was just in a meeting on the third floor [to calm down the staff] because they said he was the one who made the third floor busy, because he was noisy, he was moving around [interacting with everybody]. At that time, I saw some nurses crying, and I said, “OK, go to OPD [outpatient department]. There are two new patients who arrived today…” Two Iraqi children… Two girls, sisters. They were in a wheelchair… And I said: “We need to move on. He [gives patient’s name] left…” I told them: “In one week you will forget him because you will have other things to do” [other patients to mind]. (P76, nurse, M)

This example of the “special boy” and the pain that accompanied his departure was just one of the many daily emotional rollercoasters that played out in the hospital. Many staff members described how hard it was on them when patients finally left the RSP, saying, “We cry, feel sad and worry about them.” They reported that they used social media to keep in contact with patients, and sometimes they are able to keep in touch for several years after the patient’s discharge. One of the surgeons felt flattered that years after the surgeries patients still referred to him on Facebook: “It’s nice [to keep in touch]. One of them [a patient] just wrote on Facebook and he said that ‘It’s the tenth anniversary of my injury. Thanks for all the doctors who saved my limb.’ And he mentioned me, by my name” (P55, surgeon, M).

Such closeness, however, while unusual for a hospital environment, was not what physiotherapists and most surgeons reported. Despite some exceptions, they generally emphasized the need to maintain professional boundaries, and unlike other participants they did not refer to patients as “family” or “friends.” Most of the physiotherapists also did not consider psychological support of the patient as any part of their professional or personal responsibility, although this was quite common among doctors and nurses. Referring patients to the psychosocial team was mentioned very frequently: “We try our best to explain to the patient that this is [it]… If he wants more, we usually refer them to the psychosocial support counsellors to help us communicate: ‘don’t expect more from us.’” (P37, physiotherapist, F). The tendency to hand patients over to the psychosocial team seemed to help physiotherapists maintain their boundaries, which is not surprising considering that their daily interactions with patients were lengthier and more interactive than those of other members of staff.

Figure 9. An MSF van transports patients between the hospital and the hotel.

When I spoke with surgeons, there was a wide spectrum of opinion regarding how much information, particularly of a personal nature, they sought from their patients. Some preferred to know only the essentials – the injury and past treatment – while some sought information on the origin of injury, and one participant reported seeking detailed information on a patient’s general social situation. All participants justified this by saying that the level of information they seek helps them to manage cases clinically. Those who were reluctant to seek detailed information explained that being without such information prevents them from becoming emotional, and “emotions would cloud [their] clinical decision-making.” On the contrary, the few who did seek more details of a patient’s situation commented that this helped them to manage and support patients clinically and personally, and they considered it a part of their professional duty.

Non-Middle Eastern expatriate staff reported having limited interaction with patients due to a lack of Arabic language skills: “Here, I just have a lot of difficulties to communicate with the patients. First, I don’t have lots of contacts because of my work as a manager, I don’t directly work with the patients. And, even if I want to communicate with them, it’s very difficult because of the language [barrier]” (P32, expatriate, M). With a few exceptions, no personal relationships with the patients were reported by this group. Many, however, expressed their appreciation for the little daily gestures that took place between them and the patients: greetings, smoking together in front of the hospital, and randomly playing with kids. Most of the interviewed expatriate staff expressed a wish for more interactions, and they also stated that, despite limited opportunities, their sense of responsibility and purpose was driven by their daily observations of patients.

Empathy

What was also obvious in the daily life of the hospital was a display of a great sense of empathy by the hospital staff dealing with patients. For example, nurses gently reassured the father of a child who suffered from pain, or drivers played football with children in front of the hospital, or a surgeon expressed worries about a patient’s family situation. There were moments in the hospital when everyone was shaken by patients’ obvious suffering. I recall a day when a child was brought out of the operation theatre and a number of staff members, including the nurses, surgical assistants, and the surgeon in charge, talked about the event to me with tears in their eyes. The surgeon described it as it follows:

He [the patient] is four years old. I did surgery for him around two months ago. This patient lost all his family in a blast in Syria, and he is [now] only left with his uncle [to look after him]. He came here [to the MSF hospital] with an injury in his upper limb and has fracture in his radius in his forearm. And he has bone loss [shortened bone]. So, I did surgery for him, but when… [hesitates] When we went… When we prepared him for the surgery, he was shouting in front of the OT because he, he didn’t want to go inside… [Participant looks emotionally shaken and starts tearing up.] He didn’t want to go to the OT because he wanted his father and mother to be with him! So, we told the uncle to come with him, inside the OT. The uncle came with him and when we finished the surgery, we told him [the uncle]: “OK also come to the recovery room because when the patient wakes up from the anaesthesia, he also started shouting: ‘I want my mum! I want my dad!’” So, I was a bit like… [hesitates] I wanted to cry because it was really devastating [to witness this]. It’s really sad. And as I told you, he’s a child who doesn’t know what happened to him. This is the beginning of his journey, his life [has just begun] and he has this devastating effect [of emotional pain to suffer]. (P66, surgeon, M)

It was not an isolated event to witness hospital staff deeply shaken. During interviews, many staff members shed tears when talking about patients’ personal tragedies, the “unfairness of their situation,” and the “difficulties these individuals will encounter in their future lives.” Particularly when they reflected on paediatric patients, the participants were not disinclined to describe the sense of misfortune of these children. For instance, another surgeon commented: “A child with his father is passing in the wrong place at the wrong time, when an explosion happens. So, if they were a few minutes later or a few minutes earlier, they wouldn’t have had this accident… And this accident will change their life forever. So unfortunate!” (P63, surgeon, M). One of the housekeepers also expressed the particular sense of injustice that arises when children are affected by war: “Many of them [patients] are children who make you feel heartache because they are not guilty at all and don’t have any political or any kind of affiliation for what happened with them” (P72, housekeeper, F).

The price of providing a healing environment

Members of the hospital staff agreed that “This is not an ordinary hospital: this is a place for healing physical and emotional wounds.” Many expressed a willingness to help reduce not only a patient’s physical suffering but also their emotional distress. But these attempts to “absorb patients’ pain” left an indelible mark on MSF staff.

The heaviness of patients’ stories, even if they remained untold, was tangible in the hospital. On a daily basis members of staff complained about a lack of energy and about “stress” related to their working environment. They talked about how working with these particular patients has consequences in their personal lives. Having to “face a case that will affect you again” is felt to be a daily risk. One of the medical doctors commented: “Recent challenge that I am having [is that] I thought by now I would be desensitized and have got used to bad news or bad cases… But like I recently learnt from a case that came last week [and shook me], like sometimes this [emotional distress] will happen even if you have seen a million cases. It will come again, and it will affect you” (P91, medical doctor, M).

In daily contact with patients, the visual impact of deformed limbs and faces evokes additional emotion. I remember my first days in the hospital when I felt almost nauseous due to the emotional charge associated with the sight of deformed human bodies. As I observed injured patients during hospital rounds it became easier for me to feel and act “neutral.” But on one occasion a female patient, who had large burn scars covering her face, causing her lips and one of her eyes to pull to one side, entered my office and caught me by surprise, as I had not heard her come in and my back was turned towards the door. She gently tapped my shoulder to get my attention to ask a question. When I turned my head, I could feel an overwhelming emotional wave and was sure that in a matter of seconds my face was transparent with my feelings. It made me feel embarrassed to think I may have hurt her. I helped her with the information she sought, but an overwhelming feeling of guilt and sadness followed me through the day. As I said, over time in the hospital my emotions and reactions were slowly brought to a more neutral state, but I never felt untouched by the look of somebody with severe and visible impairments or the sight of an injured child. Members of staff, even those who had spent years with MSF, communicated struggling with the same sensation. One of the nurses noted her difficulties: “For example, five-year-old has an abnormal face, burned face, and there’s no nose, no eyes. I think this is the most difficult thing [for me to cope with in the hospital]” (P16, nurse, F).

The most frequently reported emotions in regard to interaction with patients were feelings of sadness, hurt, pain, worry, guilt, and depression, and these feelings had a high correlation to the severity of the patient’s injury and the level of knowledge of the patient’s background story. In particular, staff new to MSF, and those who could clearly recall their initiation period, disclosed how acutely emotionally challenging their adjustment had been to the working environment in the RSP. Facing cases of physical deformity and severe injury for the first time, combined with hearing patients’ stories, was described as “something you see in a horror movie”:

To be honest, the first time working here, the first month was miserable for me. Because I’ve never seen directly [such cases]. Maybe we can see [something like this] in a horror movie on TV, but this is a real story [that the patient is telling you]. It’s different, really. And in the first month, I was really shocked. [After] You hear from the patients [what they went through], you have to find a good self-care for yourself. (P57, psychosocial counsellor, M)

A male participant from the administrative department reported how his first impressions in the hospital made him cry: “The first month, the first two weeks, I was going home crying” (P58, administrative personnel, M). Loss of appetite was also commonly reported: “Very much [I felt affected]! I hadn’t eaten [properly] for two months. And I really lost eight kilos as this is the first time I work in such job in such place that’s related to wars and injuries. I always kept on crying, especially over children. I really lost eight kilos!” (P72, housekeeper, F). Both male and female participants in medical and non-medical departments described feeling shocked, crying, losing their appetite, losing weight, suffering from nightmares, feeling sad, and replaying patients’ stories in their minds after work. Some participants mentioned that they initially “could not imagine continuing doing this work” due to the shock they felt while new on the job. The vast majority then explained that after the first few weeks or months they were able to “adjust,” or “get used to it,” “manage their emotions better,” and develop a capacity to “switch off” after work hours.

The administrators, managers, and hospital support (drivers, logistic team members) expressed being emotionally affected by the situation at least as frequently as the staff providing medical care. One of the administrators clearly expressed this:

Some examples [cases], yes [have an impact on me]. I remember that, myself, I was very happy in my life and with very smiley face… Sometimes [lately], my mother and family say to me that “You look sad, why?” It’s accumulated sad moments for me. [Initially,] I didn’t feel that this has accumulated in me. But, through the years, I feel these affect every employee of MSF. (P6, administrative personnel, F)

Physiotherapists gave many such examples when describing the emotional impact of their work. One of the physiotherapists, for instance, reported: “So always psychological things [related to my work] like cut me [the feeling of harm]; they really cut me. For example, this is very simple [to explain]. Sometimes we go into depression” (P35, physiotherapist, F). Another physiotherapist also sounded desperate: “Sometimes, really, I think of changing my job. Sometimes, especially when you face not one case, a lot of cases [like this], and there is no serious effect [of your work on them] or [they are] blocked [in the therapeutic process]. Sometimes, I think it’s the time to change my work, really” (P29, physiotherapist, M).

It was alarming to hear how excruciating the emotional impact was on the surgical team at the RSP. Surgeons mostly used the term “stress” to describe their emotions. One of the surgeons explained the origin of the stress: “The stress. The stress is always present, especially in these cases. The most disappointing thing is just to go to a surgery [and come out] without any results. Without any good results” (P88, surgeon, M). Another surgeon had a similar view: “Because even after finishing the surgery, you’re stressed out because you need to know: ‘Did I do the best for the patient? Is that OK? Did that section that I did [operated] on the nerve, did it affect the nerve? Did I injure the muscular repair that they did [in a surgery] before?’ So, it’s really stressful for us as surgeons” (P66, surgeon, M).

What they were describing when they used the term “stress” involved overwhelming feelings of anxiety, depression, repressed emotions, frustration, anger, and sleepless nights worrying about the outcome of a surgery, or an ethical dilemma resulting from surgery (“Did I do the right thing?” “Did I do enough?”). The impact of these emotions was described as devastating: “The impact, first of all, is depression, [I’m talking about] myself. Because of the severity of cases. Sometimes, I see the females, middle aged, and young kids with amputation or something. How can I tolerate such things?” (P87, surgeon, M). Another surgeon made it clear that his family life was affected: “It’s a misery. Really misery. Of course, it is reflected on me, even on my family. My wife is always asking me ‘Why are you angry? All the time!’ I don’t know [what to answer]” (P87, surgeon, M). With one exception, all surgeons interviewed reported that the nature of their work in the RSP impacted their personal and family lives.

Figure 10. A physiotherapy session. Patients often undergo daily physiotherapy sessions.

My interactions with surgeons confirmed what they described during interviews. At times I was able to talk to them before or after a difficult surgery. On one occasion, for instance, a surgeon displayed visible signs of being affected – sunken eyes, a worried expression on his face. He told me that after hours of research he had found no literature to support his medical decisions on the complicated operation he was going to perform the next day. He mentioned that he was worried about the outcome of the surgery, especially since the patient was a victim of torture, with a tragic family story. What he communicated between the lines was the immense pressure he was under and how isolated and unsupported he felt in that difficult moment. Occasionally, surgeons talked about regretting their choice of profession and (jokingly) suggested that they would choose “nothing related to medicine” if they were to choose again.

Surgical work in the hospital is characterized by unique emotional and intellectual demands. With such complicated surgical cases there are often no well-established surgical protocols to follow. Some of the plastic and maxillofacial surgeons work as the single expert on the team, meaning they have no one with whom to consult when making decisions or attempting to resolve surgical problems. It is not surprising therefore that participants describe an immense sense of responsibility and consider it overwhelming. Dealing with victims of war, particularly if those victims come from a surgeon’s (or any staff member’s) home country, adds to the emotional distress.

Shared war experience of patients and MSF staff

Iraqi, Yemeni, and Syrian staff often spontaneously, without being specifically asked, shared personal experiences of the war – yet another reminder of the emotionally complex work at the RSP. Such stories were almost always accompanied by nervous twitching, facial expressions exhibiting stress, periods of silence afterwards, or participants’ apologies for talking about “such distressing details.” It appeared that their work in the hospital provided a daily reminder of the difficulties experienced in their home countries.

One member of surgical staff mentioned working under immense pressure in the context of the war in Iraq. They described events as “life changing,” “unforgettable,” and “difficult to deal with,” reporting that the events still “caused flashbacks.” One surgeon described the overwhelming situation: “I was responsible for everything, even the blanket for the patient, even the dressing, even the analgesia, everything. That’s why it was so stressful! And [responsible for] all of them [the patients]! I was the only [specialized] surgeon there for 2 million people. It was so stressful… I was working every day and on-call every day. Even Friday, Saturday – every day” (P61, M).

According to participants, a number of factors exist that make working while at war particularly traumatic. The first is the level of responsibility doctors and surgeons shoulder for medical decisions and for any questions arising from those decisions – questions that can continue for years after the surgery. The second is the intense pressure of working with a large number of severely injured people, hampered by insufficient resources and working round the clock. Finally, surgeons describe working in circumstances of extreme personal risk with hospitals under attack, guns pointed at them, and health personnel systematically targeted. These traumatic events still resonate clearly in participants’ minds, and the emotions associated with them are still very much present and unresolved.

In addition, daily worry about the people who remain under attack in their home countries, the unpredictability of events, and the frustration that “my country has been destroyed” also cause suffering. Members of staff who were not able to connect with family and friends after receiving word of new attacks and casualties appeared completely shaken. The staff originating in war-torn countries have a more intense dependence on MSF than others. Returning to unbearable working conditions at home is not an option, and, due to administrative and legal requirements, MSF remains one of the few, if not the only, employment option in Jordan. While some are accompanied by their families in Amman, many have families who remain under war conditions and depend on them for financial support. Their vulnerable position, combined with the work-related stresses, creates a sense of personal and family instability making for an extremely difficult existence.

In sum, members of staff in the MSF hospital were clearly motivated to provide a healing environment for the patients, even at their own emotional cost. The willingness to absorb patients’ pain and provide them with support was obvious. But the capacity of staff members to deal with their emotions, especially in the absence of internal professional support, was precarious. The staff that were most affected included nurses, surgeons, those originating from war countries, and new recruits. By describing their emotional crises, the staff were calling out for more emotional support, something they saw as crucial for their personal and professional wellbeing.

Are patients’ expectations unrealistic?

The sense of stress that surgeons in particular expressed was also associated with feelings of responsibility towards patients. Curiously, and in addition to the ongoing pressures related to medical decisions, some of the surgeons expressed feeling responsible for patients’ lives beyond the scope of medical care. For example, they talked about attempts to “give patients new lives,” to “reconstruct their old lives,” or to “bring them back to their normal lives.” This goal seemed overly ambitious, given that the war and their injuries had drastically changed the patients’ social and physical environments. Hence, “old lives” were gone for good, and the surgeons’ own expectations of what was achievable were unrealistic.

A fascinating aspect of our conversations was that my participants seemed unaware of the dynamics affecting them and projected the “unrealistic expectations” on to patients. Participants, particularly surgeons and physiotherapists, appeared stressed when talking about “patients’ high expectations.” This encouraged me to explore the topic further. Surgeons and physiotherapists described patients’ expectations as going beyond their capacity to solve them, and that even any talk of “managing them was not being straightforward.” Patients expected to get “back to normal,” back to “100%,” or to “run a marathon after treatment.” Some physiotherapists even reported that this mismatch in expectations caused conflicts between them and some of their patients. They further explained how challenging it was to “make the patient unconditionally accept themselves” and how much they tried to “bring patients to realistic thinking” and to “accept my vision even if it doesn’t match theirs.” One of the physiotherapists commented, for instance: “I had huge conflicts with them [patients] in the beginning because of the expectation thing. But, in the end, when they have the result and they really understand what their limits are I say [to myself]: ‘I’m really satisfied with what I’m giving to my patient’” (P36, physiotherapist, M). When asked how they proceed if they experienced resistance from the patient, physiotherapists explained that they most often refer such patients to the psychosocial team, who can work to “lower their expectations.”

Members of the surgical team were, in contrast, more concerned with the daily dilemmas they faced themselves. Uncertainties surrounding surgical procedures, doubts about a patient’s capacity to accept these uncertainties, and the unpredictability of the final treatment outcome tended to create communication difficulties with patients and uncertainty about whether the doctors could respond to patients’ expectations. Some surgeons commented that previous experience helped them to reach an agreement with patients in these difficult circumstances.

A few surgeons, however, were convinced that patients had the “right to hope,” and they explained that “without promising them the impossible” they were willing to foster these hopes. A surgeon clarified: “All the time they [patients] have hope and this is their right. If I was in their place, for sure [I would feel the same]” (P63, surgeon, M). Another surgeon gently explained his struggle to maintain patients’ hopes while at the same time balancing transparency about what was going to happen in the surgical procedure:

I personally don’t lie to the patients, even the child [paediatric patients]. I usually explain everything for the patients. I think, [in] my opinion, this is right. He should know everything about his condition… So I explain things many times. Every person [patient] cries in my office when I face such things [confront them]. But I promise them that I will do my best to help them as much as I can… At the same time, I give them hope. And, you know, depending on the case, depending on the transfer [surgical procedure], or to re-explore the nerve again [to see if something more can be done]. If we can manage something [like this], it is giving them hope. But, at the same time, I can’t promise them [the impossible]. Once the time has passed to repair such a [damaged] nerve, it can be too late. I can’t promise them [the impossible]! So, I have to be clear with the patients. I tell the patient: “We have a complication. Now, we are going to manage the complication. Not to treat the condition itself.” So, this is the conflict that I face, and the patient faces with me, personally. (P87, surgeon, M)

In spite of all these accounts, it is not the surgical options and treatment expectations that form the core of these participants’ concerns. What appears to cause the greatest stress among physiotherapists and surgeons is patients’ expressions of grief for what has been lost and their hope that things can be recovered or restored “back to normal, back to doing a favourite sport, back to running.” The fear of disappointing the patients seems to be the source that creates the greatest unease among participants since patients’ hopes simply cannot be met. Essentially, they are talking at cross purposes.

Staff members are placed in an ambivalent state between the desire to restore what has been destroyed in war and feelings of guilt and inadequacy arising from the realization that the war irreparably robbed their patients of their dignity and future. Processing the emotions that accompany such an awareness is psychically costly and in addition, many physiotherapists and surgeons are convinced that “being emotional” would “not be professional.” They think it would negatively affect their work with patients if this internal struggle were revealed.

This tendency to stay guarded and protective of ones’ emotions is common in medical settings. The literature describes the fear of exposing strong emotions arising from patient/doctor communications and labels this phenomenon as the “Pandora’s box phobia” (Hardee and Platt, 2009; Cushman, 2014). This phenomenon is defined as a “desire to avoid strong emotions, especially fear, anger or sadness,” sadness being the expected emotion in the context of the RSP. Accordingly, the “Pandora’s box phobia” results in creating barriers to empathic communication with patients and this seems to be a potential threat in the RSP.

Furthermore, the RSP at the time of this writing offered only a limited range of surgical interventions and related treatments. It is important to acknowledge that the RSP cannot fully respond to patients’ hopes, not only because they are too “high and unrealistic,” but also because there is a lack of sufficient surgical/medical expertise in the programme. For instance, no procedures considered cosmetic can be used in the treatment of burns at the RSP, and no joint can be surgically replaced, apart from hips. Providing patients with more information on procedures that may benefit them but that are not currently available in RSP, might help reduce the tensions which accompany the “mismatch in expectations.” In communication with patients, uncertainty around medical and therapeutic procedures undoubtedly needs to be explained. Trusting the patients’ capacity to deal with these uncertainties – remembering that uncertainty is part and parcel of any war context – is essential to this process. Also, acknowledging patients’ hopes could bring some relief for both patients and staff.

Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that a patient’s time in Amman does not always end with surgical interventions, let alone success. Sometimes “the injury is beyond repair or does not require surgical intervention,” or the patient is “out of the programme criteria,” or does not fit “criteria for anaesthesia.” There are administrative reasons, such as issues with visas and passports that may hinder the process of obtaining care. Or the patients themselves might refuse treatment. Between 2013 and 2016, out of 2,902 validated cases at RSP, 454 (15.6%) decided to stop treatment before the treatment plan was completed or to not receive treatment at all (analysis of the patients’ database, personal communication, Gilles Brabant, June 2018).

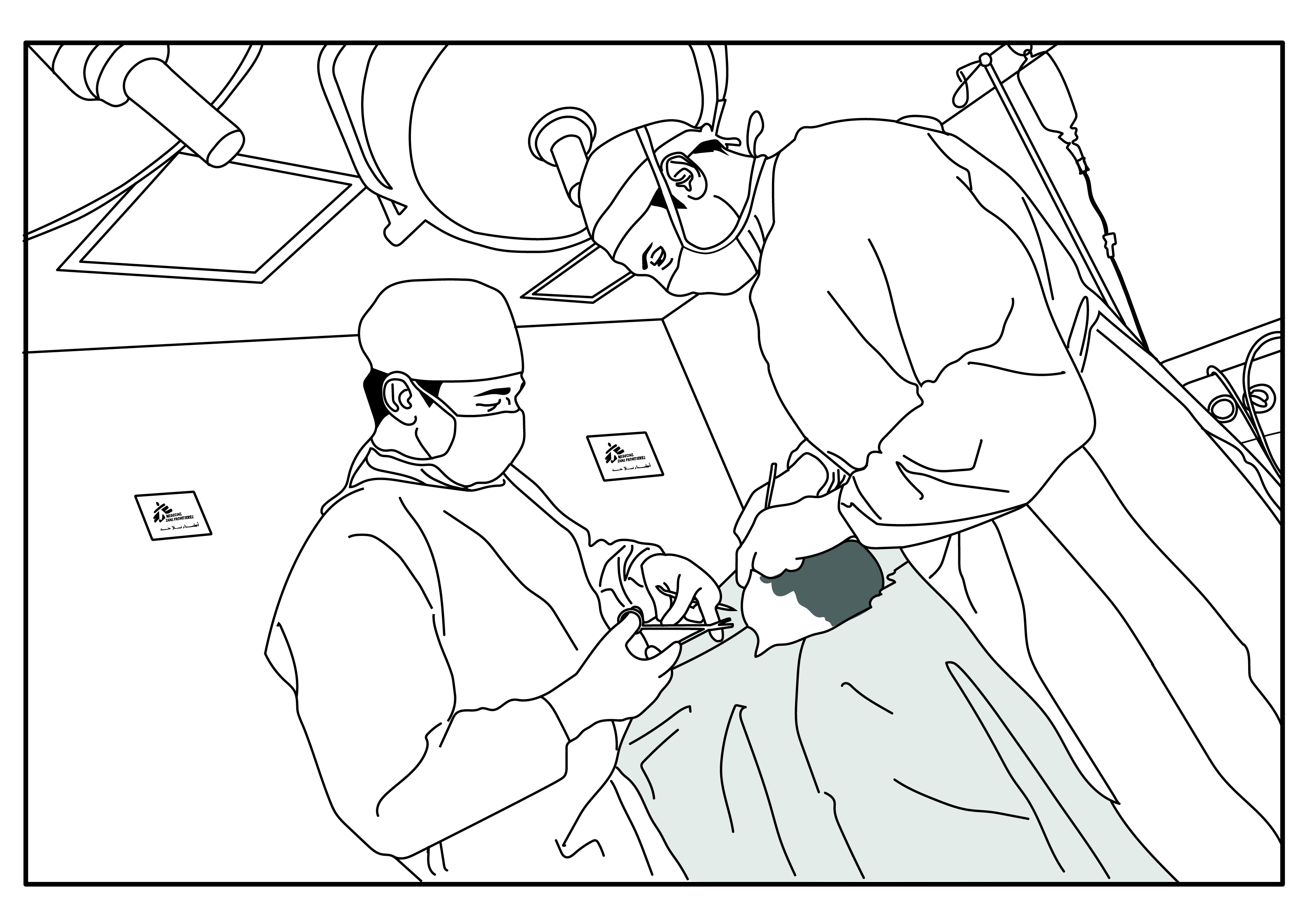

Figure 11. In the operating theatre. A surgeon and surgical assistant performing surgery.

A twenty-year-old patient, for example, left the hospital and returned to Yemen. He refused to sign the treatment plan, explaining to staff that he “came to aesthetically improve his hand,” but had been told that “they will remove the bone on his wrist.” His hand looked relatively normal, but his wrist was slightly twisted and out of the hand line. He added that he was told that “the bone needs to be removed to improve the mobility of his hand.” In considering his own hand, he commented that “my hand is mobile already.” When pressed to clarify what information he had received about the surgical procedure before his trip to Amman, he confirmed that “they told me about the removal of the bone,” but he “was not focusing enough during the information group session.” He stated that during the session in Yemen he “was worried about his travelling and his family.” He ended by stating, “I am very sorry for all the trouble, and I thank MSF for everything they have done for me. But there may be somebody out there who needs this surgery more than me.” This case was an interesting one, and I wondered if he was disappointed in the lack of acknowledgement of his wishes despite the fact that he had expressed them.

Perceptions of patients by the hospital staff

Patients perceived as passive victims

I observed a tendency to perceive patients predominantly as victims without agency and lacking the emotional tools needed to deal with the situation. This tendency was first indicated in interviews when I enquired “What is the first word association that comes to your mind when I mention patients in RSP?” “Victims” was the most frequently mentioned word, followed by “people in need,” “humanitarian cases,” and “misery.” “Resilience,” “strength,” “courage,” or “ambition” were only mentioned by a few when describing their patients. This was surprising considering that hospital staff observe patients starting a demanding physiotherapy regimen a day after surgery, or walking after having been brought to the hospital in a wheelchair, or receiving devastating news from home but remaining in the hospital dedicated to the programme. Such activities do not bring to mind victimhood.

A common phrase used when talking about patients in interviews was “We are emotionally supporting them because they need it.” The predominant opinion saw patients as passive recipients of help, dependent on MSF and the hospital staff and without their own emotional means to cope. In reality, patients developed their own coping strategies regardless of their difficult situation.

Sometimes, projecting empathy was used to cover a patronizing attitude, and to impose institutional discipline. Several of the nursing staff, for instance, mentioned getting to know a patient’s personality and then making adjustments in their relationship with them. This was partly communicated in the context of responding to the patient’s needs and sometimes in the context of responding to the institutional need to make patients respect the rules, such as the restriction on smoking. Those patients who did not follow the rules were often labelled as “troublemakers,” and the assumption that they should be compliant without questioning was prevalent. “This one is so naggy; he never stops asking questions” was an often repeated comment made by staff members in reference to a particular patient or a caregiver. One of the physiotherapists even reported “avoiding” particular “non-co-operative patients,” at the same time justifying his attitude by saying that they “carry a negative energy, because they are victims of war.” “Sometimes I try to avoid this [particular] patient,” he commented,

because, you know, we work with war victims. And the negative energy is around us, you know. You need to find the positive things, the positive energy [around you]. This non-co-operative patient is very negative patient. If we deal a lot with this [kind of] patients, after a while… At the end of the day, you will feel depressed and feel not [motivated]… Because I need to continue for another five years [in this position], I try to stay away from this patient. (P29, physiotherapist, M)

This “non-co-operation,” as the physiotherapist called it, may simply be linked to patients’ disagreements with the therapeutic plan, a conflict that many of the physiotherapists reported.

The notion that patients pose a threat to the social order in the hospital if they abandon their “passive position” and become more “active” also became obvious when the hospital director, members of the hospital management team, and I tried to launch a patients’ committee. The idea of the committee was that it would consist of patient representatives who would act as a communications body between the patients and hospital management. This patient-feedback mechanism would open a channel for patients to express their concerns and report potential abuses. I ran a number of focus groups to discuss the topic with the patients and collect their ideas on the organization of such a committee. The patients clearly communicated that they were in the best position to choose their representatives. When I reported this to the management team, one of them reacted very strongly and questioned if we were “attempting to start a new Arab spring in the hospital.” Other members of staff were also reluctant to adopt this idea and tried to push an agenda where they would be the ones to select representatives from among the patients, “because they know them, so they would be able to select those that best fit the role.”

So, on the one hand, the predominant association – patient as victim – triggered empathy among members of staff. On the other hand, this association caused patronizing and controlling attitudes towards the patients. A strong motivation in my research was to support the RSP’s efforts to improve patient-centred care. But staff perceptions of patients worked against the likelihood that patients would be involved in decisions about their own healthcare.

Children: perfect patients, perfect victims

In many ways, children appear to be the perfect patients: innocent, resilient, motivated, and progressing well in their physical recovery. Their presence in the hospital certainly brought a vibrant energy. Children often approached staff with a spontaneous hug, a chat, a need to be comforted, or with an invitation to play. Despite the rules against it, it was not unusual to see paediatric patients in the office areas of the hospital, borrowing pens or asking for printouts of pictures so they could colour. Many children adopt the hospital environment as their own and confidently move between the rooms, hospital corridors, cafeteria, and outdoor playground. One of the expatriate staff mentioned the ease with which she developed relationships with children in the hospital:

[Of all patients] I interact mostly with children. Of course, it’s always easier [to develop relationships] with children. Some just look at you because you are Western person, or because you are a woman. So, they just stare at you like you are a kind of a lion, a star, or something [unusual] like that. So, of course, it’s easier [to break the ice], because they go easily to you, they smile. It’s very easy. (P98, manager, F)

When talking about paediatric patients, staff members from all hospital departments reported a soft spot for them. Even those who meant to keep their professional boundaries in check admitted getting personal when interacting with children. Not surprisingly, staff members frequently compared paediatric patients with their own children of the same age or gender and emphasized that “We are parents as well as medical staff” (administration and management, hospital support, and surgical departments, both male and female participants). “I have a story of two-year-old kid in the hospital. When I returned from my maternity [leave], she was one year and half old. My son was at the same age as her, so every time I saw her I started crying. She had an amputation,” recalled one of the physiotherapists (P38, physiotherapist, F).

This association is combined with “children being innocent victims affected by politics,” “just starting their lives,” and “not being aware of the difficult future they will experience.” In particular, children with burns and amputations cause strong emotional reactions. Hence, paediatric patients receive a lot of social interaction with staff and at first glance it appears that children and their emotional needs are the centre of everyone’s attention.

But it was during my observations of medical procedures in the RSP that I realized that this was not the whole story. On one occasion I was present in the OT when a child was carried in by a male staff member. The child was crying in panic. In the absence of a family member to provide care, members of staff were trying their best to calm him down. They were unsuccessful, and it was only after he received anaesthesia that the crying stopped. On another occasion I observed a young girl who was already lying on the surgical table, obviously sacred and moving away from the nurses, who were trying to reassure her by saying, “It will be OK. You will get an injection and then you will just sleep.” There was no recognition that this might not be a reassuring thing to say to a child who is about to undergo surgery.

The third time I witnessed a similar lack of capacity to prepare the child for what was coming was during a consultation in the OPD. A boy of about ten years old was there with his grandfather. The boy looked completely frozen with stiff body posture, no eye contact, and no response to questions. The staff members who were there tried to explain the procedure to him, but he pushed away anyone who touched him. After persuasion failed, the staff had less patience, and three of them grabbed him forcefully, held him on the examination table, and performed the minor procedure. He was crying loudly and trying to fight back. His grandfather, who was present, was completely unable to intervene or reassure the boy, either before or after the event. The boy was eventually labelled as “unco-operative.” Later, the psychosocial team explained to me that the boy had shown signs of trauma upon his arrival at the hospital, but the staff who performed the procedure confirmed to me that they had not been told and were unaware of such a history.

Furthermore, children most frequently arrive at the hospital with their fathers as their single caregivers, and the men are often inadequately informed about what the programme expects from them. Very few children are accompanied by their mothers. The capacity of fathers to look after their children’s physical and emotional needs varies. Despite nurses covering for those fathers who were less engaged, it was obvious that some children received very little support. Those who are abandoned by their caregivers and are not properly handled by medical staff during medical procedures receive no support of their basic psychosocial needs. Arriving at the RSP with underlying psychological trauma and then undergoing a highly stressful medical procedure puts them at severe risk of developing additional psychological symptoms (for examples of post-surgical trauma in paediatric patients, see McGarry et al., 2014; Papakostas at al., 2003; Lerwick 2013; Solter, 2007).

Paediatric patients appear to be the perfect “victims.” Staff members, on the one hand, use them as examples to describe the most unjust aspects of war. And, on the other hand, they demonstrate that the insensitive and unjust treatment of children affected by war can continue inside a medical institution. It was not the lack of motivation that prevented the hospital staff from paying attention to paediatric patients, but there seemed to be a lack of the necessary skills for the emotional preparation and support of children throughout their medical and surgical ordeal.The lack of skill in paediatric patients’ management was, decades ago, common in hospitals worldwide.

Negative perceptions of Yemeni patients

My next exploration was to uncover how staff and patients’ origins played a part in perceptions and interactions. Many on the staff acknowledged similarities among all patients (Arabs, Muslims, war-affected); however, ideas about different nationalities in the hospital were quite distinct. The most neutral perceptions came from expatriate staff who were non-Middle Eastern – “We don’t interact with patients enough to notice much difference” – and from the surgical team – “You don’t notice any difference in the OT.” But representatives from other hospital departments showed no reluctance in describing the “obvious” differences between Iraqi, Yemeni, and Syrian patients.

Furthermore, the hospital culture of stereotyping patients based on nationality is passed on to new staff members. One of the newly recruited physiotherapists told me that during her orientation to the hospital, colleagues on her team described Iraqi, Yemeni, and Syrian patients in stereotypic terms. This formed a persistent storyline in the MSF-run hospital in Amman. Let us now examine what these perceptions and stereotypes are.

The vast majority of participants described Iraqi patients positively and with a sense of admiration. Representatives from all the hospital departments described them as “more educated compared to others,” “intellectually broad,” “smart,” and, as a rule, “well connected to the world.” One of the nurses, for instance, commented, “The differences [with other patients] lie in the fact that the Iraqi patient understands what’s said to him easily; his intellectual level is broader and more inclusive than the Yemeni’s” (P6, nurse, M). This also extended to the idea of a patient having clinical knowledge, and in particular the medical, paramedical, and surgical departments commented that Iraqi patients knew and understood their clinical situation “in detail” and generally “have better health education.” One of the nurses was strongly convinced of this: “Even when it comes to medical and surgical work, the Iraqi keep checking on their case on a regular basis and they disagree and discuss with the doctors. They always ask about the tests results, they ask about X-rays, they are more aware. Much more aware. They are educated, well-educated people” (P9, nurse, F).

The differences in patients’ expectations were attributed to differences in medical knowledge. Iraqi patients were often described as “demanding” in terms of wanting information, explanations, and discussions with medical staff. One of the surgeons said, “Iraqis, I can say, are more able to understand the clinical situation. They are more suspicious because usually they read a lot about everything” (P55, surgeon, M). A few participants portrayed them as controlling, saying, “they make you feel you work for them.” Despite this, the medical department in general described them as “easy to deal with,” and by and large as willing to comply with the hospital rules.

Other common descriptions used of Iraqis by staff from all departments apart from surgical were “charismatic” and “proud” (of their culture, country, food, way of life). “In general, Iraqi people, they have their own prestige… Pride. They like to be treated respectfully and with elegance” (P30, physiotherapist, M). Sometimes this same attitude was described as a tendency to “show off.” “Iraqis are proud of themselves and like to show off, but they still like to open their hearts to other people” (P27, hospital support department, M). Some Jordanian participants even described them as “more advanced” and having a “higher culture” than Jordanians, “They tell us they have more delicious food, better clothes and more beautiful nature. They always make us feel they come from a much better country” (P9, nurse, F). A tendency to treat Iraqis with more “respect, more formally/politely, with more elegance, and with more caution” was also frequently mentioned. One participant even commented that buying clothes with Iraqi children was different than with Yemeni children, as they were “pickier” and “needed more time to choose their clothes.”

Iraqi patients were complimented by the medical department for their “good hygiene practices,” their tendency to “take daily baths, frequently change clothes, and wear perfume [unlike others].” Less commonly mentioned, but still noted by the medical, paramedical, and surgical departments, was that Iraqis were “stronger than others,” and this was expressed in terms of their physical strength (“strongly built, tall”) as well as their emotional strength (“don’t express their feelings, don’t cry, able to deal with difficulties, courageous”). Their open-mindedness, “modern attitudes,” hospitable nature, and friendliness were also praised: “Iraqis are always being famous for being extremely hospitable and generous and friendly… I would certainly say that an Iraqi is quite charismatic, generous, and friendly” (P41, expatriate, M).

When it came to describing Yemeni patients, the views expressed were much less favourable. In the hospital environment many Yemeni patients appear visually distinct due to their clothing (some wear traditional wraps around their waists) and/or due to their physical appearance (darker skinned, shorter and thinner body construction). I often observed Yemenis spending time together in groups, chatting or smoking outside of the hospital. Sometimes I met them in a nearby Yemeni restaurant, where I often shared lunch with my colleagues. I had an opportunity to interact with Yemeni patients more formally when I was collecting patients’ views on the organization of an outdoor recreation space in the form of a focus group. Patient representatives from different nationalities participated in the group, and on those occasions it struck me that Yemeni patients appeared shy and agreed without opposition to what the rest of the group was suggesting.

Even before the formal interviews started, I regularly heard negative and disapproving remarks about Yemeni patients. The interviews only confirmed the scope and the nature of these negative comments. Yemenis were generally described as a unique group with little (or nothing) in common with Iraqi or Syrian patients: “Yemenis are careless about the hygiene, the appointment. When they have an appointment or a date at the OPD they forget it and they are also lazier. So that’s the difference compared to others (Iraqi and Syrian)” (P4, nurse, M). The most frequently mentioned perceptions were that they have “weak hygiene practices,” “uncivilized backgrounds,” and “low levels of education.” Staff also normally mentioned having “Difficulty understanding their language and way of speaking.”

“Poor hygiene practices” were associated with Yemeni patients by members of almost all hospital departments – paramedical, medical, hospital support, and surgical. “No habit of daily bathing, changing of clothes, regularly combing their hair.” One of the nurses emphasized that Yemeni patients were not able to use a comb: “As for the hygiene practices, they don’t bath on a daily basis. Some Yemeni patients don’t know the comb [what it is], or how to comb their hair” (P6, nurse, M). They were considered “smelly and sweaty,” and the fact that they were “not used to the Western toilets” was mentioned in this respect. The need to “force them” to take daily baths was also repeatedly cited by the medical department.

Yemeni patients were described as “uncivilized” due to their having “no schools, no streets, no technology, no electricity, no healthcare systems in Yemen.” None of the participants made a link with the war situation in Yemen and the lack of public facilities. Yemenis were also described as “primitive,” “simple,” and “conservative.” In addition, their culture and way of life were portrayed as very different from Iraqi, Syrian, or Jordanian societies. In this regard, comments were made about “making children wear hijab,” “marrying at an early age and during the first date,” and having stricter gender rules. Their way of eating (“mixing the food together and eating with hands”) and their way of speaking (“they speak fast and loud”) were also expressed as culturally inferior. The less common negative comments faulted Yemeni patients for being “lazy,” “not ambitious enough” with regard to physiotherapy, “not compliant,” “not honest,” “suspicious,” “careless about themselves and their children,” addicted (“which is in their nature”) to khat,The leaves of a shrub which are chewed as a stimulant.and “nervous/aggressive.” These perceptions were expressed particularly by medical (nurses, doctors) and paramedical departments (physiotherapists, health educators, professional carers, psychosocial team members).

The general assumption was that Yemeni patients were “poorly educated,” which includes perceptions of “poor health education,” as reported by all hospital departments. Participants sometimes attributed the low level of education to Yemenis being “hard minded,” “quick to forget,” “child-like,” “suffering from weak logic,” and “having low IQs.” One of the physiotherapists, for instance, stated: “The one who’s not compliant is the patient who’s usually really having low IQ, coming from very tough environment. Like we have patients from Yemen living in mountains, they have no contact with civilization, they still don’t care about what’s [happening] the next day” (P36, physiotherapist, M). One of the nurses had no hesitation in commenting how difficult it was to deal with Yemeni patients due to them being “hard-minded”: “Yemenis are hard people, yes, hard-minded. Yes, they are really hard-minded. It’s not easy for you to deal with them” (P18, nurse, M). These negative connotations were mentioned by both male and female members of medical and paramedical departments, and all of this was further linked to Yemenis being perceived as “challenging” compared to other patients. For instance, staff mentioned the need to “repeat things to them several times,” that “dealing with them takes longer compared to others,” and that there was a “need to reinforce rules with them.”

When I looked into the actual education level of Yemeni patients, the perception of low education proved to be incorrect. In the database of patients’ electronic medical records, where the level of education is reported (based on 242 entries, between April 2017 and March 2018), Yemeni patients were on average more educated, with more than 50% attending secondary school, than Syrian or Iraqi patients, of whom more than 50% have only a primary-school education. The level of university education was comparable for the three groups (Iraqi: 9%, Syrian: 8%, Yemeni: 8%). These surprising numbers show how little information the hospital staff actually had about the patients, even when dealing with them on a daily basis, and how their negative perceptions of Yemeni patients remained unquestioned.

The most positive descriptions of Yemeni patients had to do with their demeanour. The point was made that they were “extremely thankful,” “kind-hearted,” “pure,” “sweet,” “gentle,” “sociable,” “respectful,” “honest,” and that they “have a good sense of humour.” This type of comment came most frequently from administration and management and surgical departments, and it was striking that none of the surgeons commented on poor hygiene or low IQ among the Yemenis. Participants from all departments other than administration and management perceived them as “inclined to accept everything, without complaining” and being “the most appreciative and forgiving” of all the patient groups.

Often the challenge in communicating with Yemeni patients, as explained by the logistics, medical, and paramedical departments, was attributable to linguistic barriers. Yemeni Arabic is considered a conservative dialect cluster with many classical features not found across the Arabic-speaking world. It is considered significantly different from the Arabic spoken in Syria, Jordan, or Iraq. The participants were unsure if they correctly understood Yemeni patients and vice versa. They reported having to seek help from caregivers or other Yemeni patients in an attempt to translate what the patient was communicating.

One of the Yemeni members of staff pointed out that some Yemeni patients “feel ashamed to say, ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I don’t understand.’” He further explained that a Yemeni patient “will feel like he should say ‘yes’ regardless of his understanding, so he won’t say ‘No, I didn’t understand.’” I witnessed this when following one of the nurses on her daily routines. She visited with a Yemeni patient and started explaining the pain medication he was taking. At the end of her clarification, the patient asked a couple of questions and thanked her for an explanation. He confessed that he “didn’t understand what they were telling him during the surgical round.” When I enquired how the medical staff ensured that Yemeni patients understand them, one of the participants mentioned that “he reads this in their eyes.” These accounts indicate that communication between hospital staff and Yemeni patients is compromised, which raises the question of how much medical information remains uncommunicated or misunderstood. Furthermore, Yemeni patients seem reluctant to ask questions and do not debate the decisions of their healthcare providers.

In my observations, a Yemeni staff member was always called upon to mediate between Yemeni patients and other staff when a misunderstanding occurred. This staff member was asked daily to “speak for” the Yemeni patients. He would “explain treatment plans and make patients agree on them,” sort out disputes, deliver information, and comfort patients whose family member had died, or try to convince other members of staff to “believe what the patients were saying” if they felt suspicious. Without this particular staff member, Yemeni patients would have remained voiceless.

When participants talked about Syrian patients, it was in a more dispassionate tone than that used to describe Yemenis and Iraqis. To a certain extent, staff saw many similarities between Iraqi and Syrian patients, but the Iraqis still held the most positive place in their hierarchy. Syrians were talked about with less of a sense of fascination, and it was a narrower sample of departments that had positive views. Still, Syrian patients were described as “open minded” and “well educated,” especially in relation to Yemeni patients, and they were seen as generally easy to deal with due to their cultural proximity to Jordan in the use of the Arabic language, food, dress, habits, and technology. Jordanian staff members in particular brought out the similarities they felt with Syrians. One of the members of the psychosocial team, for instance, stated: “The cultural things in Syria are the same as here in Jordan. Because they are very close to Jordan, it’s not far from here to Syria. To Syria you can go by car; you can go by bus or anything. So this is the effect of [geographical] proximity on the [proximity of] culture. And they can adjust with all cultures, the Syrians can [unlike others]” (P57, psychosocial department, M). One of the nurses made a comparison to Yemeni patients, adding: “I understand everything he says. As for the culture, their clothes, the way they treat others are all very close to us. They’re closer to us as Jordanians, more than the Yemeni, much closer” (P9, nurse, F). Less frequently, Syrians were described as “easy to adjust, having good acceptance of their injury, having good compliance with medical recommendations, the most united as a community of patients, easier to express pain, hardworking, technologically advanced and generally sociable.”

The medical, paramedical, and surgical departments held some negative perceptions of Syrian patients, commenting that they were “demanding” – for example, “asking for additional explanations,” especially if they faced surgical complications. A few participants also mentioned that they “complain a lot” and are “the least satisfied with treatment.” Other participants from the paramedical and surgical departments commented that Syrian patients “are not honest when they report their medical complaints” – they are seen as using their complaint to extend their hospital stay.

Patients transforming the “self”

Al Mowasah hospital is a cultural melting pot. Regardless of nationality, similar age groups frequently mix together smoking, chatting, playing table games, or relaxing in the hospital outdoor area. Yemeni patients seem to spend more time in the company of their own countrymen, but the effect of the cultural blending was most obvious in relation to them. Younger male patients wearing traditional Yemeni clothes on their arrival at the hospital soon replaced them with jeans and a T-shirt. Their haircuts also became more daring over time. This may have been an effort to avoid the widespread negativity about what are perceived as traditional Yemeni characteristics, but the neutralization over time was unmistakeable.

What was seen as a cultural transformation was praised by some of the staff members interviewed. Yemeni patients were described as “open to new things,” “willing to change,” and “all of them eventually adapt to the new culture.” In particular, participants highlighted a desirable tendency among Yeminis to accept “Iraqi culture” (for instance, “all children enjoy dancing Iraqi dances, even the Yemeni,” and “Yemeni patients start speaking with an Iraqi accent”), and members of staff were pleased to report that Yemeni patients over time “become more modern” and “improve on their style.” One of the participants described that “They became really nice people using laptops, using social media, everything and improving their dressing style, compared to the first time in the hospital, when they were really not well dressed.” This participant further added: “We are supporting them culturally and from the style point of view” (P54, M). One of the nurses described how she intervened when she saw a Yemeni girl wearing a hijab and long dark dresses “at a young age.” The nurse proudly described how she managed to convince the girl’s father to replace his daughter’s clothes with “something more colourful, adjusted to her age” (P3, nurse, F). This indicates that some staff members eagerly participated in the cultural transformations.

The transformations that occurred in the hospital were not only cultural. I observed a fascinating process through which patients gradually transformed how they portrayed themselves to the world. The behaviour of female burn victims from all nationalities rapidly changed during their time in the hospital. Some of them had large deformities on their faces, necks, and hands such as contracted skin, depigmentation, and a rough appearance. Upon arrival at the hospital they were shy and guarded and made obvious efforts to cover their scars. They also tended to spend more time in their rooms. Over time they left their rooms more frequently, exposed their faces, wore makeup over their scars and generally acted with greater self-confidence. Two weekly events organized by the psychosocial team exclusively for female patients contributed to these changes. I observed the so-called DJ parties. These women-only parties happen behind closed doors on the fourth floor of the hospital. Lively music plays from the recording machine, and the female patients who gather are dressed up. Some of them take off their head scarves and dance energetically. They certainly seem to be freer with their bodies. Another event that perhaps also supports female burn victims in their transformation is the weekly shopping they do together at the local market. The objective, as explained to me, was to expose the women to the public so they could work on social acceptance. Female patients who go shopping together walk out of the hospital looking confident and empowered.

Thus, the hospital provides a closed and protected environment where a patient can develop and adjust to his/her new self. Group pressure, from both fellow patients and staff members, to “appear less Yemeni” has an impact on the Yemeni patients, and group support for female burn victims helps to foster new identities for these women. With so much time spent restoring their bodies and emotional health, it is consistent that the hospital and the patients would make an effort to develop new social identities. What is the result of such a transformation after the patient returns home? This question remains, and we will explore it next.

Période

Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay informed about our latest publications. Interested in a specific author or thematic? Subscribe to our email alerts.