Responses to a seasonal high incidence of sever acute malnutrition operational lessons and policy changes

Jean-Hervé Bradol

Dr. Jean-Hervé Bradol, Former President of MSF-France presented data based on MSF's experience in Niger that showed the implementation of the UN recommendation for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition was not possible in a high burden setting.

What's the goal?

Severe and acute malnutrition means that the associated mortality is high, mainly within the 6-36 months age group.

Responding to seasonal high incidence requires sustaining large scale and costly operations over a number of years. Consequently, we cannot aim to totally normalize the deteriorated nutritional status of a whole population of children using only a medical approach.

The objective is to decrease the mortality associated to poor medical nutritional status by preventing the occurrence of too many severe and complicated cases and by treating most of the existing ones. In addition to nutritional treatment, measles immunization and treatment of the most commonly deadly infections are needed to optimize the impact on child mortality. The provision of safe drinking water will also be ideally required to increase the impact. Most medical institutions do not have the capacity to cover all of these needs together.

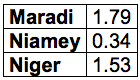

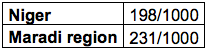

Figure 1. Retrospective under 5 years old mortality, over 3 months, per 10 000 / day, June 2008

Enquête nutrition et survie des enfants 6-59 mois, Gouvernement du Niger (Institut National de la Statistique, Direction de la Nutrition du Ministère de la Santé)

National Institute of Statistics (INS), Niger and Macro International Inc. Demographic Health Survey / Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006 (DHS/MICS III) Calverton, Maryland: INS and Macro International Inc; 2007.

Figure 2. Under five mortality

National Institute of Statistics (INS), Niger and Macro International Inc. Demographic Health Survey / Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2006 (DHS/MICS III) Calverton, Maryland: INS and Macro International Inc; 2007.

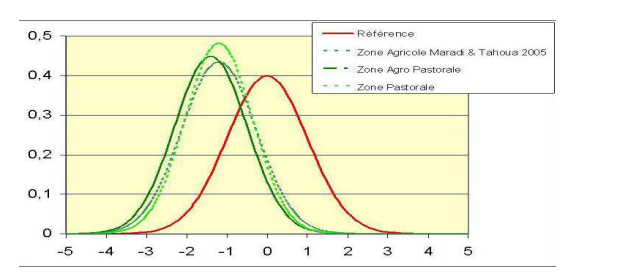

Figure 3. Décalage vers le bas de l'ensemble de la distribution du poids-taille des enfants de 6 à 59 mois des régions de Maradi et de Tahoua en septembre et octobre 2005

Source : République du Niger, Cabinet du Premier Ministre, Cellules Crises Alimentaires, Francis Delpeuch (Iram). Evaluation du dispositif de prévention et de gestion des crises alimentaires du Niger durant la crise de 2004-2005 : Synthèse concernant les aspects nutritionnels

What 's the target population?

Today there is a consensus to treat severe and complicated cases. Complicated cases means that whatever is the deterioration of their nutritional status, minor or major, the association with at least one additional pathology threatens their life at short notice. These cases are costly to diagnose because they only represent a small proportion of children scattered in a large population requiring costly and large scale screenings. Treatment is also costly as it requires many qualified medical staff. The last WHO standard to define severe cases is appropriately more inclusive for the youngest patients, but it increases the workload.

However we cannot limit our action to this group of complicated and severe cases for several reasons. In the first place, only half of the deaths associated to under-nutrition occurs in this group. The other half is found within more moderate forms of malnutrition.

The second reason in favour of enlarging the number of children receiving a food supplement is to reduce the operational complexity and the cost needed to handle numerous complicated and severe cases. We are aiming at reducing the proportion of severe and complicated cases during seasonal peaks to ensure that usually weak public curative institutions will be able to deal with number of children.

We must enlarge the target group to include more than severe and complicated cases if we want to maximize the impact on the mortality, but we still need to restrict the group as our resources are limited.

Can we give food supplements only to acute moderate cases?

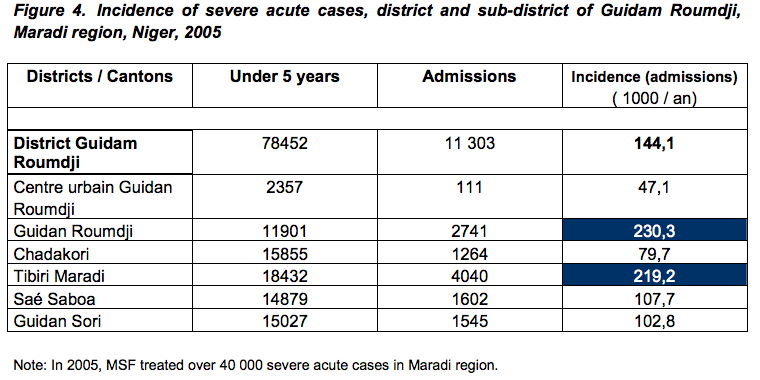

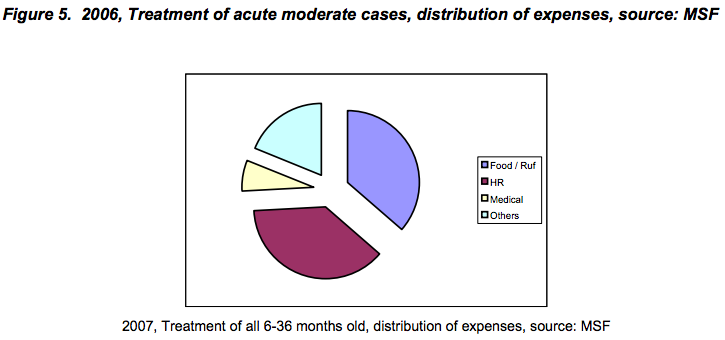

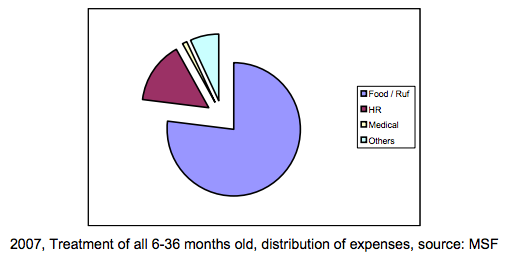

In 2006, in the district of Guidam Roumdji, Maradi region, Niger, we treated moderate cases (almost 30 000). In 2007, we switched to the delivery of a food supplement to all 6-36 months old children (around 60 000). With an extra expense of 30% in 2007, we have achieved the same outcome in lowering the seasonal pick. Though the overall cost was higher, expenditure on food for children increased from 35% of expenses in 2006, to 77% of expenses in 2007. Of course the number of individualized medical procedures was 4 fold less in 2007 compared to 2006.

Conclusion: Ideally, the target group in high incidence settings should be severe and complicated cases for individualized medical procedures, and all the 6-36 months age group for food supplement distributions at least during the worst season.

What’s the food?

Ready to use (mothers), including an animal source (very young children growth needs), high nutrients density (small stomach volume of young children). There are no valid reasons, besides shortage of funds, to keep on working with substandard food.

The cost of nutritive spreads is an obstacle. In our example of Guidam Roumdji, an increase of 30% costs when covering a whole age group (compared to the cost of treating only acute moderate cases), disappears if the price per kg of the spreads decreases by half. This is clear that the current price is an obstacle.

What’s the main obstacle?

What’s the main obstacle to adapted responses in highly affected areas? Only severe acute and sometimes moderate acute cases are eligible to receive food. This is not manageable in hot spots because one will be overwhelmed by the number of cases that requires complex and costly medical cares and one will still miss a significant group at risk of dying. Moreover, most of money will be allocated to institutions and staff not to starving children.

As it has been done for HIV, malaria and tuberculosis nutrition treatments should be delivered for free to non for profit medical teams and underweight children should be treated as early as possible, there is no reason to wait until the child is on the verge of dying to intervene. The main obstacle is the lack of political will to cover the cost of milk, sugar, oil and vitamins necessary to treat starving toddlers.

From a political point of view, the decision to treat all underweight children in highly affected areas has never been taken neither by national nor international institutions. This would be a drastic change? Is it an utopia? This is comparable to what did recently happen with infectious diseases like hiv, malaria and tuberculosis. This is also comparable to what happened with vaccines for Epi, more than 25 years ago.

To cite this content :

Jean-Hervé Bradol, “Responses to a seasonal high incidence of sever acute malnutrition operational lessons and policy changes”, 1 septembre 2008, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/medicine-and-public-health/responses-seasonal-high-incidence-sever-acute-malnutrition-operational

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute