Those who remember. DRC, Empire of Silence

Marc Le Pape

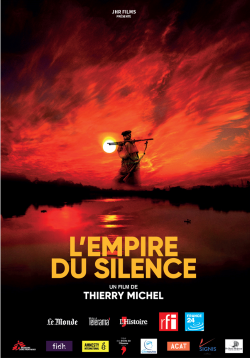

The film Empire of Silence, directed by Thierry Michel, examines the massacres committed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1996 to the present. In this blog, Marc Le Pape introduces the film’s structure, some of the principal witnesses to the mass executions and some of the military and political actors responsible for them, and Congolese reactions to their impunity.

Thierry Michel’s narrative starts with some background on the Rwandan Patriotic Front’s military victory and ascension to power in 1994, which led to the massive exodus of Rwandan Hutus, who congregated in camps near the Rwandan border in Zaire. In October 1996, bolstered by an alliance with Uganda and Congolese rebels, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) violently broke up the camps and pushed further into Zaire. In November 1996, the UNHCR and USAID estimated that 700,000 Rwandan Hutus had fled toward Zaire’s interior.

I watched Empire of Silence (JHR Films) several times, slowly – a nightmarish succession of massacres. Beginning on 6 October 1996, the attack on Lemera hospital by the RPA and their Congolese rebel allies: 30 patients executed (the town of Lemera, in Congo-Zaire, is close to the Rwandan border). At the end of the film, a priest from Nganza parish in Kasaï-Central gives his account: in 2017, Congolese Army “shock troops” killed 417 villagers in two nights, “boys” in particular. And then, Thierry Michel’s voice and the text: “The massacres bloodied the country – in Kivu, in Kasaï, in Ituri, in Équateur, in Katanga. It’s impossible to list them all.”

Those who remember

Rather than recount the film, I will instead talk about the people, the Congolese, who remember, who were there and talk about it. Here are two of them: Dr. Mukwege in Stockholm and Lemera, and the provincial director of the national Red Cross section’s disaster relief service, who was working in Mbandaka in 1997.

When it was attacked, the Lemera hospital was being run by a “young doctor” named Denis Mukwege. He was interviewed years later on the hospital grounds, where he said, “The impunity began here” (several armed UN soldiers, identifiable by their blue helmets, were there during the interview, providing security for Dr. Mukwege). In Mbandaka (Équateur Province), the provincial director of the Red Cross disaster relief service spoke of the massacres. Many Rwandan Hutus fleeing the RPA had reached Mbandaka on the Congo River, which they were hoping to cross; only a minority succeeded. The others “were massacred, truly massacred,” reported the Red Cross officer. He was filmed walking along the docks where the attackers fired on those unable to cross the river.

There are many Congolese in the film besides these two witnesses, and they describe situations they witnessed either where they were living or in the course of investigations: priests, journalists, academics, lawyers, and just ordinary people (both city dwellers and villagers).

A priest is speaking, he is inside a church (a series of shots show the white walls, the alter, and then the wooden pews): “It was 24 August 1998. Rwandan soldiers surrounded the church and massacred 139 people with axes, right here in the church. The priest was beaten to death with an axe in the rectory […]. No one dared to explain what I am explaining right now. Someone who burned a thousand houses, hundreds of people, was made captain, was made colonel, to reward him. […] You have to kill a thousand people to become a general in the Congo.” As he speaks, a series of shots show the monument commemorating the massacre, on which is inscribed in red capital letters: “In memory of the 24/08/1998 HOLOCAUST.”

At another point in the film, a few shots show a demonstration in Kinshasa against the United Nations Mission in the Congo. A UN vehicle burns, set ablaze, as Alphonse Maindo (a political scientist at Kisangani University) speaks: this Mission “is not here to do a gruesome count of the victims […]. It was deployed to prevent that. To prevent precisely that having to come to count the number of people killed and wounded. […] There is total impunity. This is sacrificing an entire nation, with the risk that it could happen again at any time. We are sitting on a time bomb.”

The unpunished

And then there are the people with lots of power, the unpunished. Seeing them offers some historical landmarks and casts light on their military actions. They include presidents Mobutu, Kabila (father and son), Museveni (Uganda), and Kagame (Rwanda). They also include some generals: Rwandan James Kabarebe (who commanded the Rwandan forces who entered the Congo starting in October 1996) and Congolese generals Gabriel Amisi (code name “Tango Four”) and Eric Ruhorimbere, whom journalist Sonia Rolley identified as someone who committed crimes in South Kivu in 2013 and who later commanded the armed forces in Kasaï. And finally, some Congolese “warlords”; there were, and still are, many. A few of the film’s sequences show two of them, in uniform: Laurent Nkunda, the archetypal “warlord”, who was a Seventh-day Adventist minister (showing off “our chapel”) and head of a murderous rebel movement active in Kivu from 2006 until January 2009. He justifies his armed operations based on his pastoral authority, namely “the duty to protect the flock […] when the threat is armed”. Equateur Province strongman Jean-Pierre Bemba had himself filmed commanding his own army, known as the “Congo Liberation Army”, to demonstrate his (real, documented) power: standing, alone, in front of his followers.

The well-known massacres

Since the “Congo War” started in 1996, much information has been gathered and published in the form of investigations, news stories, reports, books, and university teachings on the strangeness of the Congo. By this I mean the severity and multiplicity of events that no longer seem to surprise, as if they were a normal feature of the Congo, past and present – a place of massacres, rapes, pillage, and destruction. The film is entirely in keeping with that information, in particular by naming and filming those who remember and condemn.

On several occasions the film also shows, accurately and in detail, how difficult it has been to gather and publish information about the massacres. This was the case, in particular, at two points in the film: in the part about the Mapping Report OHCHR, Mapping Report; https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/CD/DRC_MAPPING_REPORT_FINAL_EN.pdf (which will be discussed subsequently) and in the part about two members of the Group of Experts on the DRC, Michael Sharp and Zaida Catalan, who were executed on 12 March 2017 in Kasaï, where they were investigating. They were forwarding their discoveries to some UN colleagues (one of whom talks about the execution and the moments preceding it). In addition, at several points in the film, some officers from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (HCHR) stress that they knew about the massacres committed in the Congo since 1997.

The Mapping Report, drawn up by the HCHR after painstaking investigation, includes a list of the massacres committed in the Congo from 1993 to 2003. The film gives an account of its dissemination: the (fruitless) attempts to block its publication and then the circumstances of its release – in particular, the determined efforts of journalist Christophe Châtelot (Le Monde) and finally “the leak” and publication of the Report, in its entirety, on 27 August 2010. Though meticulous and rigorous, the report was disparaged endlessly, particularly in France and Rwanda, by the people involved and by others – journalists and academics – who preferred, and still prefer, an alternate narrative in which the immensity of the massacres and the identification – even partial – of those responsible have disappeared. These journalists and academics are outraged that anyone would attest to the reality and density of the massacres, rapes, and pillaging; they minimise and sometimes deny them, questioning the Rwandan Patriotic Army’s involvement despite Congolese corroboration. It is true that we don’t know all of the data collected by the Mapping Report investigators; there is a list of presumed perpetrators of the massacres, but it has not been revealed. The Congolese demonstrators appearing at the end of the film call for the creation of an international criminal tribunal against the perpetrators identified by the Mapping Report’s authors.

In the Congo, on the Mapping Report’s tenth anniversary, women marched carrying a banner that read: “Debout MAPPING. Rise up”. Rise up against whom? As the film attests, there is indeed an international “empire” powerful enough to stymie, for years, any legal action regarding the massacres that have nevertheless been documented by investigations, reports, news stories, witness accounts, and films.There are many essential documentary sources dealing with the massacres in the Congo and the leaders that ordered them available online. See, in particular, the publications by the Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project and the annual reports from the United Nations Group of Experts on the DRC, starting in 2004 (https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1533/annual-reports).

To cite this content :

Marc Le Pape, “Those who remember. DRC, Empire of Silence”, 10 mars 2022, URL : https://msf-crash.org/en/blog/war-and-humanitarianism/those-who-remember-drc-empire-silence

If you would like to comment on this article, you can find us on social media or contact us here:

Contribute

Commentaires

Une très bonne initiative !

Add new comment